GUEST LULLY MIURA WRITES FROM THE UNIVERSITY OF TOKYO – Koike Yuriko became the first female governor of Tokyo in a surprise landslide earlier this month. The election was held following a money scandal involving the former governor. While Koike’s victory is a step forward for women in Japan, it could also be the long awaited catalyst for real reform in Japan.

Tokyo’s governor is one of the most visible political roles in Japan. The governor is chosen by more than 10 million voters and is in charge of an economy the size of Mexico or Indonesia. In Japan’s parliamentary system, prime ministers are chosen by a majority of the House of Representatives, so in some sense, the Tokyo governor has a stronger direct democratic base. The governorship is even more special now because the city will host the 2020 Olympics, making the governor one of Japan’s faces to the world.

Japan has long struggled to elevate the role of women in society. It ranks among the worst in the ratio of women in politics, government, and business. The Abe administration has made efforts to promote the rise of women mainly through economic logic. Japan’s shrinking population is a threat to its workforce and the long-term viability of the economy. The recovery generated by “Abenomics,” the nickname for Abe’s economic agenda, has worsened the shortage of workers. Foreign labor is one way to fill the gap, but both conservatives and liberals have a very negative view of opening Japan’s borders to immigration. Women are the most promising frontier to find new workers in Japan.

Is Koike’s rise to power a victory for the advancement of women in Japan? The answer is mixed.

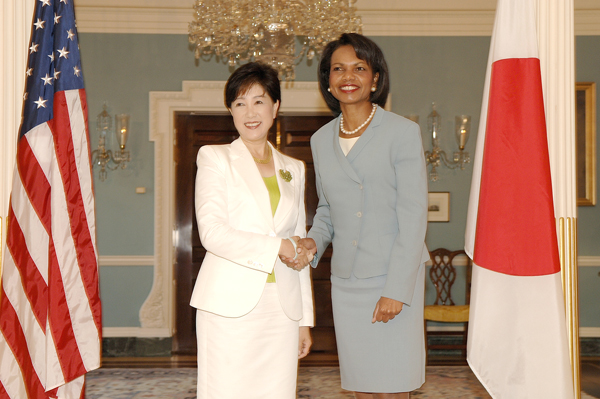

Clearly, Koike’s gender played a role in the election. She battled a technocrat-turned-politician backed by the LDP-Komeito coalition that rules at the national level, and a renowned left-leaning journalist backed by several opposition parties. Despite having no support from any of the political parties, Koike gathered votes from half the LDP base and a third of the opposition’s base. Koike has been a member of the House of Representatives from the LDP, and a vocal conservative throughout her career, so her success with liberal voters is especially remarkable. One of the likely reasons she transcended the ideological spectrum is her appeal among women. The fact that Japanese voters supported a woman in such a critical role is in itself encouraging.

Koike’s success might have an impact on the Democratic Party’s leadership race in September. Renho, the leading candidate, is backed by Okada Katsuya, the current party president, and the DP mainstream. If Renho wins, she would be the most visible opposition to Abe.

Yet, women in Japan are far from achieving the goals laid out by Prime Minister Abe, and their profile is much lower compared to other developed nations. Abe’s target was “30 percent of leading roles held by women by 2020” in politics, government, and business. Shamefully, after three and a half years in power and four national elections, the ratio of women in Parliament is still in the single digits. This isn’t because voters rejected the female candidates the administration presented; the LDP candidate list didn’t come close to including enough women. (Neither did the list of the Democratic Party.)

The rise of women in business has been worse. The business community pushed back hard against the government’s attempt to make the 30 percent target an enforceable quota, insisting that it be left to “self-govern” to achieve the target. Often, this insistence on “self-governance” is code for inaction and this has been no exception: the ratio of women in board-level positions, or even managerial positions, isn’t close to 30 percent. Abe’s target is laughably unrealistic and the government has simply stopped citing it. In sum, women don’t have a lot to show after the Abe administration’s four years in office – save for Koike’s rise to power.

What awaits the new governor? To put it mildly, a huge mess. The two previous governors resigned as a result of money scandals, so restoring trust in the system is a serious and immediate task. That assignment is made even more difficult by the alleged scandals surrounding Tokyo’s campaign to host the 2020 Olympics. Part of the problem is the cost of hosting the games. The budget has more than tripled, and risen far more than a trillion yen, or $10 billion. Public suspicion is mounting about public works contracts given to companies close to political bosses.

Koike’s biggest challenge will be the opposition in the Tokyo Metropolitan Legislature. In local politics in Japan, the legislature must approve the budget presented by the governor. Without its cooperation, Koike will accomplish very little. Koike attacked the legislature for lack of transparency and called it a “black box” during her campaign. She did not outright accuse legislators of corruption, but promised to set up a special investigative team to look into wrongdoing surrounding the Olympics. The LDP-Komeito coalition that controls the legislature is not likely to be in the mood to cooperate with Koike after those attacks.

Koike has a choice about how to proceed. She could move to compromise and rebuild her relationship with the legislature. There are signs that she might be headed in this direction. Alternatively, she could follow up her threats to the legislature with action and expose the “old guard.” Her choice is of symbolic importance to Japanese politics as it is the choice faced by many reform-minded politicians. With a clear mandate from Tokyo voters, Koike can tackle this challenge head on.

There is a near consensus that Japan suffers from a lack of structural reform. Many of the reforms undertaken by other developed nations during the 1990s and early 2000s have not been implemented in Japan. As a result, Japan suffers from low productivity in all but a few export sectors. Per capita income has stagnated for 20 years. It has had the worst growth profile among the major developed economies combined with the worst national debt. What is perhaps most critical is that the outlook isn’t any better. Japan’s shrinking population is a serious drag on growth, and the world’s fastest aging population will put further pressure on Japan’s debt.

Whether Koike will follow through with her reformist agenda is unclear. She is well positioned to do so, however – perhaps more so than any other politician in the past. The coming weeks and months will reveal whether she will be just a poster for women’s advancements or the real reformer Japan so desperately needs.

Lully Miura (yamaneko.nikki@gmail.com) is a lecturer at the University of Tokyo and a researcher at the Policy Alternatives Research Institute. The full online version of this PacNet article is available here. The above was an excerpt via the Center for Strategic and International Studies. PacNet commentaries and responses represent the views of the respective authors.