KIANA KARIMI AND LIAM ROGERS WRITE — What a scene: White, Blue, and Red stripes encapsulate a Moscow stadium with a crowd roaring in cheers and clad in Z’s giving a grand welcome to a celebration of “unity” while awaiting the illustrious dictator himself, President Vladimir Putin. The Russian government threw a grand fête to mask the humanitarian crises and genocide they committed. The latter is seemingly farcical to outside spectators — for instance, Oleg Gazmanov, a Russian singer, performs a cheap parody of Queen’s “We Are the Champions” with a hint of Hannah Montana’s “Best of Both Worlds” to prelude the dictator’s entrance with a patriotic chant.

As the former KGB agent struts his way towards center stage, the eerie air gives a scent of a pop-culture villain who wants to normalize his war-mongering antics. Casting a spell of misleading patriotism to incognizant Russians, the war criminal lauds his military efforts to ensure the safety of the Russian Federation.

While Vladimir Putin creates a nonsensical assurance to his people, Russian soldiers round up Russian protesters, Romanian endocrinologists frantically create radiation pills due to the Russian nuclear threat, and Russians pillage the cities of Ukraine. Week after week, Ukrainian fighters are still in combat against Russian forces. The office of UN High Commissioner “recorded 4,633 civilian casualties,” including 1,982 killed and 2,651 injured. The antagonist, aggressive forces target hospitals, schools, international journalists, and innocent civilians. Even more so, the latter soldiers resort to abhorrent methods of bellicosity — sexual violence of girls as young as 14 and women as old as 83.

The world mourns for the citizens of Ukraine as Russia continues its invasion. While the Russian war in Ukraine was nothing of a surprise, no one could have ever foretold the viciousness of Russia’s abhorrent tactics.

Out of fear of triggering World War III, countries and world leaders chose not to participate in warfare. An example of such is the United States refusing to declare a no-fly zone. However, most of the world has unified itself over a single objective: to somehow cripple Russia.

As the atrocities multiply, many ponder if and, more importantly, when Russia, specifically Vladimir Putin, will be prosecuted for war crimes. Can we legally call Putin a war criminal?

Enter the International Criminal Court. The ICC tries, investigates, and prosecutes those accused of the highest crimes, such as genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and crime of aggression. The foundational document of the tribunal was adopted on July 17, 1998, and put into force on July 1, 2002. The current 123 state parties of the Rome Statute agreed to give the tribunal authority to hold “individuals charged with the gravest crimes of concern to the international community” accountable for their actions in the global arena.

Thus far, the ICC has investigated countries and world leaders. However, often there is no resolution: the accused must be present at The Hague; and the accused must accept and be cognizant of the accused crimes. It’s inconceivable that Vladimir Putin would accept his culpability and be willing to lave Russia and present himself at The Hague.

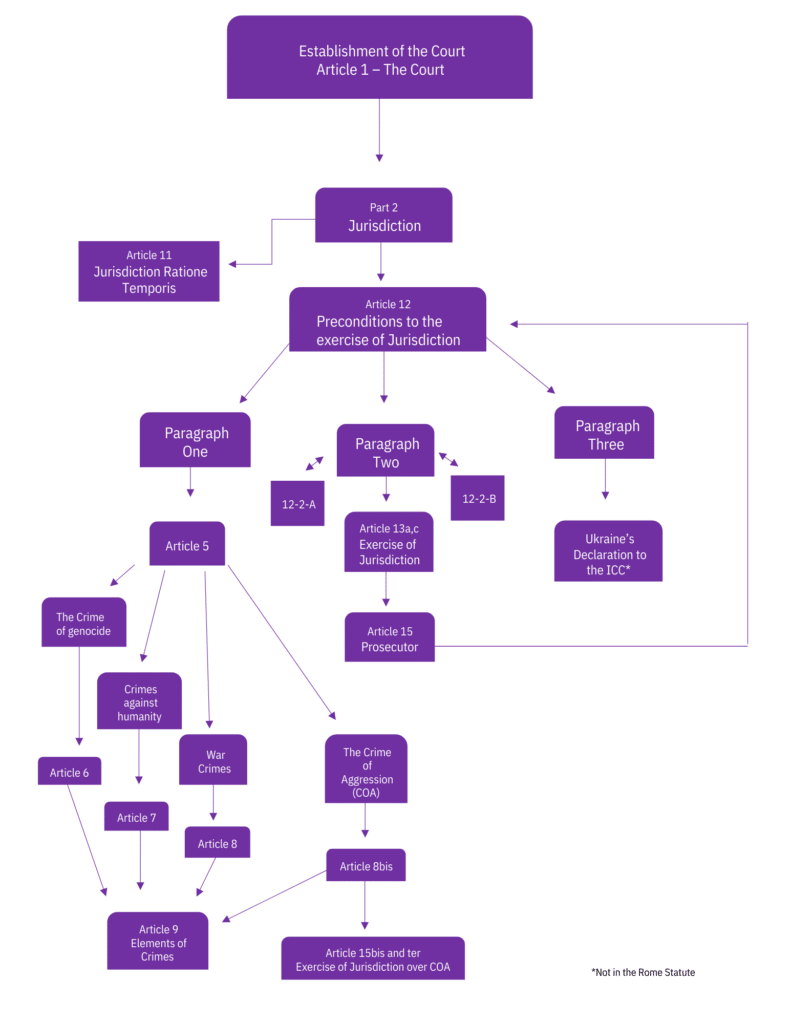

Additionally, navigating the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court is not straightforward. Investigating and probing the Rome Statute has been dubbed as the equivalent of following the ball in a pinball machine, requiring a lot of to-and-fro readings. Withal and most importantly, we must examine if the ICC has the jurisdiction to prosecute anyone in Russia, let alone Russian nationals like Vladimir Putin. However, a fundamental issue is apparent: Neither Ukraine nor Russia are parties to the tribunal. But the Rome Statute, the principal document of the ICC, has a complicated understanding of jurisdiction that gives it some room to work around the territorial authority hurdle.

To understand the Rome Statute, Rajika Shah, Professor at Loyola Law School and Director of the Loyola Genocide Justice Program, further clarified the tribunal’s unique jurisdiction and explained whether the ICC could try Vladimir Putin for Crimes of Aggression in a session with us.

To begin our analysis of the Rome Statute, we start with Part 1, Establishment of the Court Article 1 The Court of the Rome Statute, which begins the conversation of authority and jurisdiction.

An International Criminal Court (“the Court”) is hereby established. It shall be a permanent institution and shall have the power to exercise its jurisdiction over persons for the most serious crimes of international concern, as referred to in this Statute, and shall be complementary to national criminal jurisdictions. The jurisdiction and functioning of the Court shall be governed by the provisions of this Statute.

Looking at the article, the second sentence provides evidence of how the ICC can prosecute individuals, in this case, Vladimir Putin. However, before we can determine whether Putin can be hauled to the ICC, we must determine the ICC’s jurisdiction. The latter leads us to examine Part 2, Jurisdiction, Admissibility, and Applicable Law, of the Rome Statute, to Article 11 Jurisdiction Ratione Temporis and/or Article 12 Preconditions to the Exercise of Jurisdiction.

Article 12 – Preconditions to the exercise of jurisdiction

1. A State which becomes a Party to this Statute thereby accepts the jurisdiction of the Court with respect to the crimes referred to in article 5.

In the above article, there are a couple elements present here — the exercise of jurisdiction over people and jurisdiction concerning certain crimes, with a time element. Before we can examine these elements, one problem lies ahead. Russia is not a state party to the Rome Statute. Thus, it doesn’t meet the first precondition to jurisdiction. We move on to paragraph two of Article 12.

2. In the case of article 13, paragraph (a) or (c), the Court may exercise its jurisdiction if one or more of the following States are Parties to this Statute or have accepted the jurisdiction of the Court in accordance with paragraph 3:

(a) The State on the territory of which the conduct in question occurred or, if the crime was committed on board a vessel or aircraft, the State of registration of that vessel or aircraft;

(b) The State of which the person accused of the crime is a national.

Again, before we dive into Article 12 Paragraph 2, we need to look at Articles 13a and c to see how the Court can exercise its jurisdiction over a person.

Article 13 – Exercise of jurisdiction

The Court may exercise its jurisdiction with respect to a crime referred to in article 5 in accordance with the provisions of this Statute if:

(a) A situation in which one or more of such crimes appears to have been committed is referred to the Prosecutor by a State Party in accordance with article 14.

The above applies because there are currently 42 state parties referring to the situation.

(c) The Prosecutor has initiated an investigation in respect of such a crime in accordance with article 15.

Now, we need to look at Article 15, Prosecutor.

Article 15 – Prosecutor

1. The Prosecutor may initiate investigations proprio motu on the basis of information on crimes within the jurisdiction of the Court.

The Prosecutor explicitly asks states to refer the crimes to the ICC in a press release, so the above applies, and Article 13A is fulfilled. Going back, let’s look at the first “if” situation on Article 12 Paragraph Two A, “if one or more of the following States are Parties to this Statute or have accepted the jurisdiction of the Court in accordance with…” Ukraine is not a state party to this statute, so the following is not applicable. Looking at Article 12 Paragraph Two B, the key word is “national.” Putin is a national of Russia, however, Russia is not a state party. Again, the following is not applicable.

Examining the second “if” clause allows us to move to paragraph three of Article 12.

3. If the acceptance of a State which is not a Party to this statute is required under paragraph 2, that State may, by declaration lodged with the Registrar, accept the exercise of jurisdiction by the Court with respect to the crime in question. The accepting State shall cooperate with the Court without any delay or exception in accordance with Part 9.

The named state parties are Russia and Ukraine. Russia has not accepted the Court’s jurisdiction in accordance with Article 12 Paragraph 3. However, Ukraine issued a declaration to the ICC in 2015

Reading the declaration, the last sentence of paragraph two extends the time frame in which the Court can investigate crimes in the territory of Ukraine. However, we now must specify the crimes for which a state can be prosecuted and judged. The first paragraph of the declaration gives the ICC jurisdiction for crimes against humanity and war crimes. However, Russia cannot be tried for crimes of aggression.

In addition, circling back to the Rome Statute, conditions four and five are not met in Article 15bis, Exercise of Jurisdiction over Crimes of Aggression. Thus, Putin cannot be prosecuted for crimes of aggression at the ICC. The ICC does not have jurisdiction. However, states could have a special tribunal specifically to prosecute Russia for the crime of aggression.

More eminently, the ICC has the jurisdiction to prosecute for crimes against humanity, war crimes, and genocide. (Details about the latter are found in Articles 6, 7,8, and 8bis of the Rome Statute). In a review of the Russian War in Ukraine, which, in effect, can be dated back to the annexation of Crimea in 2014, it is evident that Russian President Vladimir Putin is accountable under International Law.

As the investigation, trial, and conviction of Putin is underway, the key development of the case, at this time, revolves around the validity, extent, and review of evidence that directly illustrates the crimes that President Putin has committed in this invasion.

News media and/or social media shows direct evidence of nefarious violations of the Rome Statute. For instance, Russian soldiers kidnapping Ukrainian Mayor Yevhen Matveev and holding 500 people hostage violate the war crime of taking hostages, Article 8(2)(a)(viii). Ukrainian TikToker Marta Vasyuta provides a bountiful amount of videographic evidence of the Russian army bombing and striking different places such as an oil terminal, residential areas, food markets, and hospitals. She also shows the Russian army using thermobaric weapons such as vacuum bombs, shooting Ukrainian protesters, and attacking civilians during evacuations. Clearly, all the people and places listed are not military objects, and these atrocities violate multiple provisions of the Rome Statute. However, it is to the discretion of the ICC to use evidence like the latter to try Russia and Russian nationals.

Through media sources, whether through novel media like TikTok or programming through CNN, documentation of the atrocities is abundantly clear as newer tragedies torpefy Ukraine. As proceedings in the Hague commence, evidence of Russian aggression depicts a narrative of a war-torn country and the necessary evidence to prosecute Russia by outlining and displaying these actions, furthering the level of credibility, and increasing international exposure to the crimes, we, as the active public in the global community, can support the ICC as its officials progress with their proceedings.

KIANA KARIMI and LIAM ROGERS are recent graduates of Loyola Marymount University.