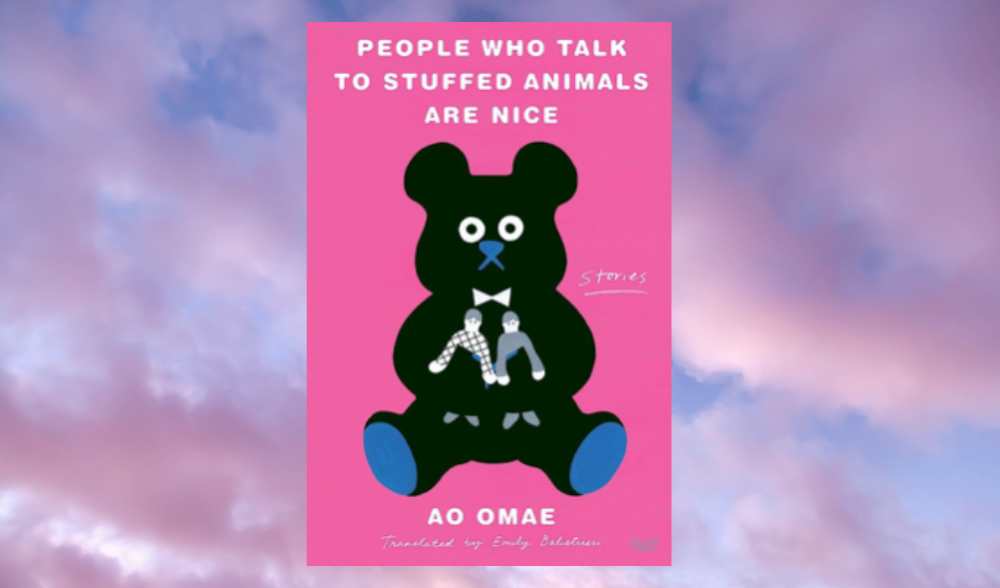

SASHA SENGELMANN WRITES – It is no secret that opening up to others may often be a daunting task, for there is no telling whether one’s display of vulnerability will be met with compassion or criticism. Such an idea is apparent in Ao Omae’s People Who Talk to Stuffed Animals are Nice (2023), in which characters turn to inanimate objects – bottled water, stuffed toys, bath towels, and imaginary friends, respectively – in search of solace.

Born in 1992 in Hyōgo Prefecture, Japan, author Ao Omae made his debut in the world of Japanese literature in 2016. He has since gained traction for his gender-conscious works, known to deeply analyze, question, and critique boundaries outlined by the status quo, particularly those of Japan. With Omae’s age placing him at the cusp of the end of Generation Y and the emergence of Generation Z, he is able to simultaneously incorporate his experience with outdated societal nuances into his writing, and also effectively address experiences of today’s contemporary youth. In People Who Talk to Stuffed Animals Are Nice, translated by Emily Balistrieri, common threads of estrangement from society and self-discovery link the young-adult protagonists in each story. Boldly defying implications of Japan’s status quo, each narrative provides perspicaciously liberal explorations of this generation’s navigation of relationships, family dynamics, sexuality, and social outlook as part of its passage into adulthood.

All four tales in People Who Talk tenderly delve into each narrator’s emotional turmoil, which all challenge the idea of “normalcy” as defined by societal standards. In Realizing Fun Things Through Water, Omae’s progressive perspective on gender roles and expectations in marital relationships is reflected in the protagonist, Hatsuoka, objecting against such constructs. The title novella follows university student Nanamori’s struggles with detaching himself from ingrained social norms – particularly those regarding gender, masculinity, and misogyny. Grappling with such themes is often a source of frustration for him, yet it also proves to be critical in his journey towards solidifying his sense of identity.

Similarly, the protagonist of Bath Towel Visuals experiences pivotal character development, prompted by disdain for Japan’s traditional emphasis on women being docile and submissive. In alignment with the other anecdotes in this collection, she also discovers an unorthodox coping method to ease her struggles, highlighting the quirkiness of Omae’s writing that weaves refreshing slivers of whimsicality in his overall stoic, melancholy prose. Lastly, Hello, Thank You, Everything’s Fine, incorporates elements of fantasy and mysticism as a refreshing contrast to the wholly secular nature of the book’s other stories. Balistrieri’s masterful translation of this title accurately approximates what the actual story entails: a facade to achieve the impression of being a nuclear family.

Through each character’s battles with loneliness in the face of crushing social pressure, it becomes clear to see how audiences at the intersection of adolescence and adulthood may relate – especially in the current world. Omae’s efforts to fabricate characters that are realistic and simultaneously in and out of touch with reality provide additional depth and value to his writing, and prompt his audience to contemplate its own place in society. His success in doing so also emphasizes the need for more young writers such as himself, to push forth literature that encourages as well as encapsulates Japan’s expanding comprehension of the intricacies of sexuality, women’s rights, and interpersonal bonds.

Edited by executive editor Ella Kelleher.