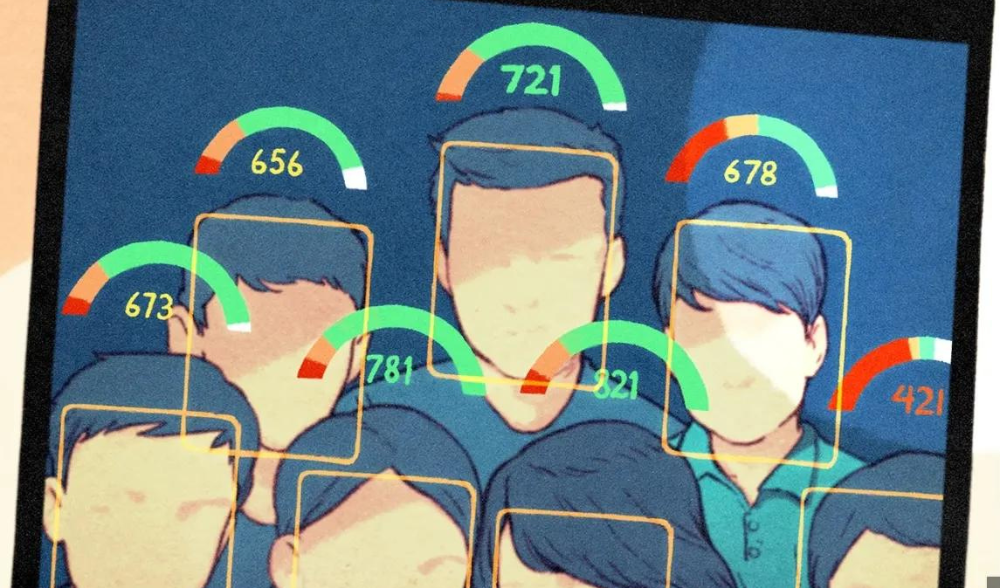

AHMED AL SHAHRI WRITES – The Chinese Communist Party developed the social credit system in 2014 to monitor the behavior of its population and assign every citizen a ranking based on individual credit. So how is it working out?

According to Business Insider, in an article published in 2021, the rankings have been determined by the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), the People’s Bank of China, and the Chinese court system. The ‘private sector’, including tech companies, have their own scoring systems, with each employee assigned a unique code to measure their real-time social-credit score. To date, it is estimated that 80% of provinces, regions, and cities have already introduced some version of the SCS, and more than 33 million businesses have already been given a score under the corporate social credit system.

Some in the Western media refer to these developments as “sinister” and “Orwellian” systems of control. Former U.S Vice President Mike Pence sounded the alarm by saying, “China’s rulers aim to implement an Orwellian system premised on controlling virtually every facet of human life.” But in reality, the SCS has yet to be fully developed and implemented, so the so-called social credit system is yet to be fully evident. Although the draft of the Social Credit Law released in December 2020 may provide clarity and guidance on how the SCS will be implemented and regulated, the final law has not yet been released.

How is it supposed to work? The social credit system assigns citizens a score based on their behavior and actions, including their online activity, spending habits, and compliance with laws and regulations.

Organizations operating in China have to align with the regulations to operate successfully in the country. High scores result in benefits such as easier access to loans and visas, while low scores may lead to restrictions on travel and access to certain services. For instance, by the end of 2018, Chinese authorities had declined citzen-purchases of travel tickets no less than 18 million times. Similarly, some people can find themselves barred from purchasing business-class train tickets and are restricted from staying in the best hotels.

Is the social credit system a tool for the Chinese government to exercise control and suppress dissent?

Critics think so, arguing that the criteria used to determine scores are opaque, and they note that the data is often either incomplete or inaccurate. Moreover, there are concerns about the privacy implications of the system, as it requires the collection and analysis of vast amounts of personal data.

According to Liao Li, a finance professor at famed Tsinghua University in Beijing, “There are many irregularities in the personal credit market; this is not beneficial to the long-term development and trustworthiness of the social credit system.” Similarly, the idea of name-and-shame tactics and sanctions may not serve to reduce outstanding debts and/or improve the credibility of individuals and organizations.

A lot more needs to be done to improve the system. Yet proponents argue that the SCS is a move forward—that it will lead to a more trustworthy and honest society, as (theoretically) citizens will be incentivized to behave in a responsible manner. They also argue that the system will help to combat fraud and improve the efficiency of government services, and improve the financial credit industry. They say that the government is looking at the system to help rather than punish people. Yes, they say a lot!

Regardless of one’s perspective, clearly the SCS represents a significant shift in the relationship between the Chinese government and its citizens. As it continues to evolve and expand, the SCS will likely have far-reaching consequences for both China and the world, as other countries view and evaluate it. Will some follow suit? If so, then we’ll have to credit the Chinese system.