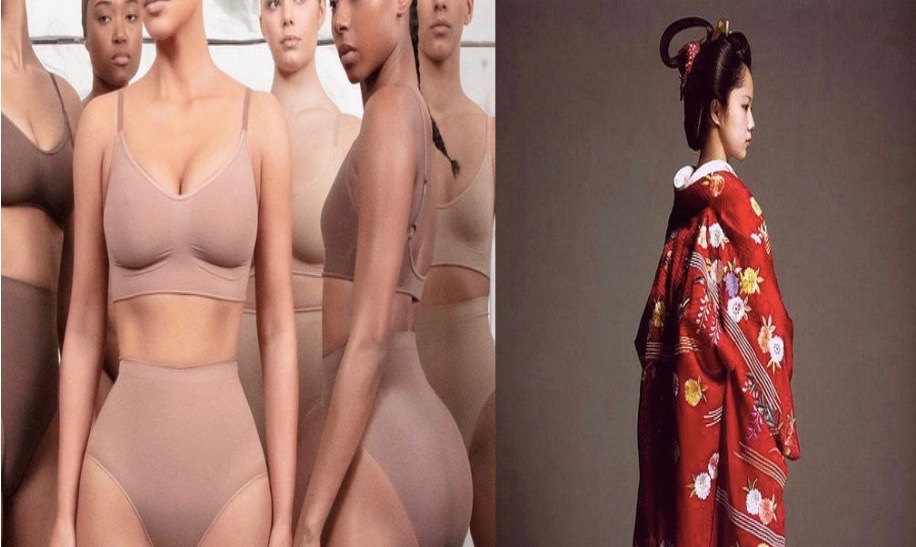

NILE BROWN WRITES –In June, Kim Kardashian’s shapewear line of form-fitting, nude-colored undergarments, called “Skims,” made its debut. Finally.

Back then Kardashian tweeted about her new shapewear line: “Kimono is my take on shapewear and solutions for women that actually work.” Kimono? Where did that come from? Critics, fans, and contemporaries were quick to challenge the brand name on grounds of cultural appropriation.

Just what is “cultural appropriation” in the fashion world? A variation of a standard ethnic style that is not attributed to those who first created it. It’s a kind of stolen merchandise—(stolen from a culture, not a star). In the digital publication Dazed, it is written that “By mainstreaming the style with no regard for the religion, brands may find themselves ostracizing the very customers they’re actually trying to include.”

Yuko Kato, a Japanese news editor for the BBC, tweeted after the announcement, “Nice underwear, but as a Japanese woman who loves to wear our traditional dress,👘 kimono, I find the naming of your products baffling (since it has no resemblance to kimono), if not outright culturally offensive, especially if it’s merely a wordplay on your name. Pls reconsider.” Then “#KimOhNo” became a trending topic on Twitter.

The traditional kimono traces its origins to Japan’s Heian period, from 794 to 1185 AD. The wide-sleeved, full-length outfit was worn regularly by both men and women. The kimono has since become ceremonial dress worn only on formal occasions, which added to its offensiveness as a name for underwear.

Kardashian responded to the backlash: “I understand and have deep respect for the significance of the kimono in Japanese culture.” The next day Mayor Daisaku Kadokawa of Kyoto shared an open letter, asking Kardashian to reconsider the name. A week later she agreed. Then on Aug. 26, she tweeted, “After much thought and consideration, I’m excited to announce the launch of SKIMS Solutionwear™.”

Let’s not pick on Kardashian, however. There’s no shortage of cultural appropriation, or accusations of such, within the fashion industry. Last year, Gucci faced backlash from the Sikh community after white models took to the runway wearing turbans. The Sikh Coalition tweeted: “The Sikh turban is a sacred article of faith, @gucci, not a mere fashion accessory. #appropriation. We are available for further education and consultation if you are looking for observant Sikh models.” But in May of this year, those same turbans were sold for almost $900 and an uproar arose again. Nordstrom then pulled the item from its website and issued an apology, but Gucci did not address the concerns. And with the growing $230 billion modest fashion market (meaning, the trend for women to wear less skin-revealing clothes, especially in a way that satisfies their spiritual and stylistic requirements for reasons of faith, religion or personal preference) more brands—from Calvin Klein to Versace— are selling traditional Islamic garments with alias brand names. In fact, we now have white models dressing as geishas to retailers using the racially loaded “Oriental” term to describe a print for a shirt.

It’s fine to follow fashion trends, and design accordingly. Variations on an ethnic theme are also okay. Let’s just give credit where it is due—to the honored histories and cultures of the styles from which they were born.