Asia Media International Editor’s Note: The following Blog from inside mainland China appears courtesy of chublicopinion.com; it is currently the best insider narrative of what really happened in Wuhan that we have seen as of Tuesday 4 February 2020.

For most Chinese people watching the unfolding of Wuhan’s coronavirus emergency, the situation escalated dramatically on Jan 20, almost 20 days after it was first made public (and downplayed).

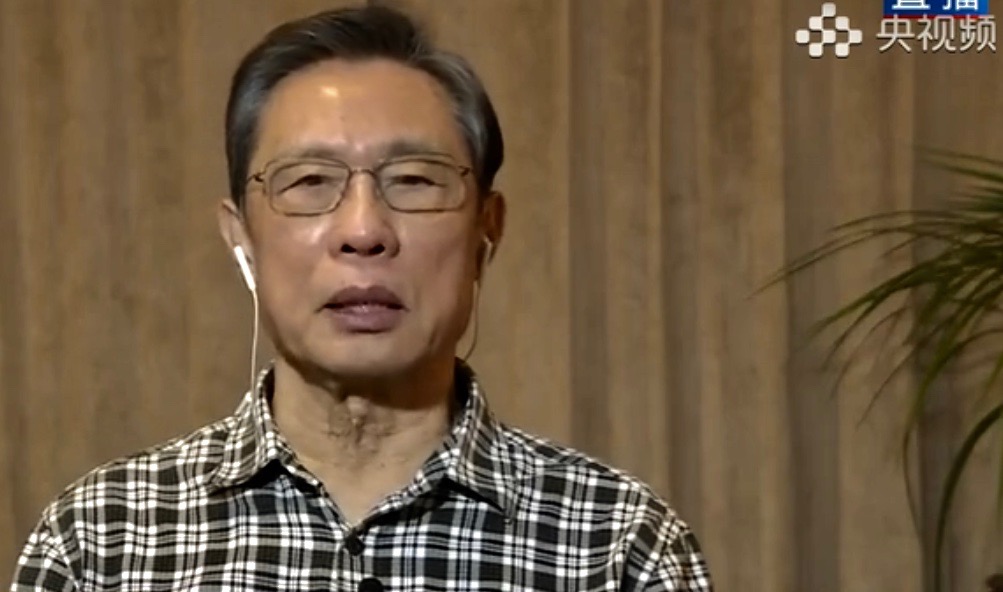

In a stunning appearance at a press briefing organized by the National Health Commission (NHC), Zhong Nanshan, the 84-year old respiratory specialist and leading expert of the NHC’s high level advisory group, admitted to a room full of reporters that the coronavirus transmitted from human to human. He also revealed that medical workers had been infected. In a televised conversation with “News 1+1” anchor Bai Yansong later that day (a kind of Anderson Cooper moment), Zhong went further by suggesting that people should avoid leaving or going to Wuhan altogether. That morning, Zhong was invited by Premier Li Keqiang to give input to a cabinet meeting on the outbreak, following President Xi Jinping’s first official instruction since the emergency. But it was Zhong’s re-appearance on the national scene that changed the tone of the national conversation in a decisive way.

By now, the contour of the novel virus’s journey to the center of a global health crisis is relatively clear. At the beginning of Dec 2019 and probably earlier, the coronavirus likely broke through species barrier at a wet market in the middle of Wuhan, a Yangtze River city of 11 million, and infected its first victims. The infected suffered from an acute form of pneumonia and from there, it began to spread. What’s also clear, is that before Jan 20, the discourse around the epidemic was defined by the local authority’s slow and mumbled response. According to multiple timelines recreated by Chinese social media users, the first case of infection appeared as early as early December 8. But it was not until Dec 30 did the Wuhan health authorities acknowledge the existence of a “pneumonia of unknown reason” through an internally circulated notification that was later leaked. The notification installed a strict gag order on the condition. Furthermore, on Jan 1, 2020, the authorities “sanctioned” 8 citizens for spreading “rumors” about the disease. After media got hold of the notification, local authorities admitted that 27 cases had been diagnosed, most of which associated with business owners in Huanan Seafood Market. But the market, a suspected reservoir of the virus, was allowed to open for business till the new year, closed only after the situation went public.

Zhong Nanshan’s blunt admission waked the country up to a life-threatening situation that was uncannily reminiscent of 17 years before, when the disastrous 2003 outbreak of SARS killed more than 700 globally and traumatized the entire country. At that time, Zhong’s appearance on CCTV’s flagship news show “Face to Face” directly challenged the false assurance provided by Health Minister Zhang Wenkang. Zhang famously laughed at a foreign journalist for wearing a facial mask at his press conference in early April 2003, when the SARS epidemic in Beijing had, in fact, spun out of control. He was dismissed, together with Beijing’s mayor, less than two weeks later, a turning point of the battle against SARS.

The symbolism of Zhong’s re-emergence was reassuring. The doctor, together with Dr. Jiang Yanyong, who risked political persecution to alert international media about Beijing’s SARS outbreak, were the conscience of China’s medical community that gave people hope in 2003. He proved that 17 years later he still garnered formidable respectability among the Chinese public. A photo of the fatigued octogenarian napping on a train to Wuhan circulated wildly on Weibo as people paid tribute to the doctor. And Weibo users lamented the fact that 17 years later it still took the old man to convey the bad news to the nation.

Later events would prove that the sense of reassurance was both misguided and pre-mature. The China of 2020 is economically and technologically much more advanced than the China of 2003. And yet, the Wuhan outbreak exposed its frail and weakened “social immune system” that, for a new generation of Chinese, was a painful discovery and political education.

Sensed that the political signals were changing, Caixin, the business weekly that’s regarded the bastion of journalistic professionalism, was among the first to send reporters to Wuhan, while people were running from it in flocks, some for the disease, some for Chinese New Year, the country’s most important holiday every year when hundreds of millions went on trips home for family reunions. Caixin’s first dispatches from the Wuhan scene was from the Tongji Hospital and the Wuhan railway station, documenting the measures that were belatedly installed. Apparently, Zhong Nanshan’s advice of not leaving or going to Wuhan was not heeded as a great number of travelers were still roaming the halls of the busy terminal. The epidemic couldn’t have happened at a worse time.

Inside the city, reporters were picking up much more disturbing signs of trouble. A group of Sanlian Weekly reporters revisited the closed Huanan Seafood Market, and bumped into business owner Huang Chang who was collecting stuff from his shut shop. Huang was infected. And so was his wife. But both were allowed to move freely in the city as hospitals were either not sufficiently alerted or unprepared to receive patients from the seafood market. Sanlian’s report brought people’s attention to the battered hospitals of Wuhan, many of which were already showing signs of stress: longer lines at the emergency rooms, shortage of testing kits, wards filling up with patients that must be isolated…

For some, such on-the-ground muckraking represents a flashback to the not so distant past that is destined to be short-living. Li Haipeng, a veteran investigative journalist reminded his Weibo followers to “take a last look at the glorious sunset”, as these were China’s last remaining media outlets still defending public interest. Between 2003 and 2020, the one difference that is obvious to anyone watching, is the decline and degradation of China’s non-state media industry. At the turn of the century, China’s newly (partially) liberalized newspapers and magazines were pursuing news and scandals with a ferventness not unlike their Western counterparts. The SARS episode established media outlets such as Southern Metropolis News, the history making daily broadsheet and Beijing Youth Daily as a force to be reckoned with. Theirbrave breaching of gag orders sounded the first alarm bells in Guangzhou and Beijing, two epicenters of the SARS epidemic. The following years saw waves after waves of cleansing and disciplining of the sector. Watchdogs became a rare breed and investigative journalists became an endangered species. The decline of media is so obvious that even Hu Xijin, chief editor of Global Times and a shrewd defender of Party policies, conceded that constant curtailment of media’s power by “unrelated government departments” (referring to those not directly in charge of supervising media) had significantly undermined society’s ability to raise alarm about imminent danger.

17 years after SARS, the country had proactively dismantled a key part of its immune system against such danger. And the price was dear. On Jan 23, people in China woke up to the news of Wuhan being sealed off by government order. The great Yangtze River city had closed all the transportation terminals. No one could get out of the city anymore.

The drastic measure was met with confusion, panic and hysteria. At one point, even the mayor of Wuhan wasn’t clear to whom the travel ban applied. The tone of media reports quickly darkened from Zhong Nanshan’s measured alarm to Guan Yi’s despair. Guan, a top virologist at the University of Hong Kong, described himself as “scared” in a one-on-one interview with Caixin. The SARS and bird flu veteran conceded that in his brief visit to Wuhan before the seal-off, he witnessed a city completely unarmed. “It would be 10 times worse than SARS.”

As mood turned, the horrendous situations in Wuhan’s hospitals began to surface. Sanlian Weekly and Beijing News, another newspaper joining the on-the-ground press corp, both turned their attention to crowded wards and emergency rooms. The picture they depicted was horrifying: medical workers were being overwhelmed by a large number of incoming patients. The capacity of hospitals were reaching its limit, turning themselves into hazardous public spaces. Undiagnosed patients were being turned away, who lingered between home and hospital. In 2003, SARS claimed the lives of a huge number of medical workers as hospitals failed to quarantine patients immediately. But isolation needs space that Wuhan’s over-crowded hospitals did not have. Social media was quickly filled with images of long queues at health care facilities. A heartbreaking video of a frontline doctor making desperate phone all to his superior, crying and cursing, got widely posted, then censored, and posted again repeatedly.

Like their predecessors in 2003, Wuhan’s medical workers confronted an onslaught of a poorly understood virus like barehanded soldiers. The heroism was all the more poignant when their sacrifice was avoidable. There was no shortage of irony when the life-and-death situation in hospitals were put side by side with the festive mood of Wuhan’s administers. It turned out that on the eve of Jan 21, less than two days before the closure of the city, leaders of Wuhan and Hubei province were enjoying an exuberant Spring Festival show put up specifically for cadres. Social media also noticed that on Jan 19, just one day before Zhong Nanshan’s warnings on national TV, Wuhan government organized a massive celebratory Spring Festival banquet involving 40 thousand families, a blatant disregard of containment principles. More attentive observers began to connect the dots. Wuhan’s belated official release of infection data stopped just 5 days after the virus outbreak was made public on Dec 31. Between Jan 6 to Jan 16, the city’s public health authority reported not a single new case, leaving the impression that the epidemic was under control. The silence coincided perfectly with official conferences and celebration schedules: between Jan 6-11, provincial cadres were all gathering in Wuhan for the annual sessions of the local People’s Congress. Apparently, the political ritual could not be disturbed.

As indignation against the officialdom mounted, another kind of anger was collecting force. Guan Yi’s pessimistic message on Caixin met with rebukes from social media, with netizens calling him scaremongering and “showboating“. His choice of leaving Wuhan immediately was also sneered at as an act of defection. Some went further to suggest that Guan had a track record of exaggerating virus situations, citing his alarmist comments around bird flu outbreak in 2013. Caixin itself was not spared from such criticism, prompting the author of the interview to defend the article publicly, insisting that including such voices was healthy for the battle against the virus.

The backlash against Guan Yi and Caixin was not uncommon in the national outburst of opinions around the outbreak. If things have changed in the 17 years since 2003, one clear difference is the emergence of grassroots online defenders of the state against what they see as “subversive forces”. Experts, media, and individuals may all become targets of intimidation in the name of “rumor busting” (piyao). The unifying value of such online actors (some showing signs of state coordination, others spontaneous) appears to be the upholding of social order and stability in the face of extreme uncertainty and chaos. Any utterance that is considered to incendiary or misleading is treated with harsh, and in many cases personal, criticism. Media questioning of official statistics and amplification of non-officially condoned voices run the double risk of both government censorship and punishment by public opinion. What’s tragic is that right in the middle of the Wuhan emergency, this advanced online “immune system against dissent” were activated to attack individuals with real needs and grievances.

In the confusions of the seal-off, three Wuhan Weibo users posted descriptions of what their aunt had experienced. The suspected coronavirus patient was turned away by overcrowded hospitals. Her conditions worsened rapidly at home, was finally admitted into an Intensive Care Unit, and died two days later. She never had the chance to be formally diagnosed. When her nieces posted about her death, they understandably expressed dismay. One of them described gruesome scenes at hospitals, some of which she heard about from interactions with an ambulance driver. This became her sin. As influential Weibo accounts picked up the story, they were displeased and irritated by the distraught posts. Part of the account sounded implausible. And how come three seemingly unrelated Weibo users all of a sudden started to post about an “aunt”? Quickly, a narrative of “bad elements” trying to sow mistrust about government disease response began to develop around the three cousins. Discrepancies of their accounts were highlighted. Suspicious wordings were scrutinized. The most eye-catching theory was that they were internet agents hired by the Taiwanese regime to stir up discontent on the mainland, based on their occasional language usage. Piqued by such storylines, thousands of Weibo users descended on the cousins’ Weibo space to insult them. “Disgusting bitches!” they cursed. When Weibo belatedly verified the identity of the three women, a few accusers made public apologies. Weibo later suspended some leading accounts in this episode.

The cousins were not alone. All over Weibo, desperate help seekers from the epicenter of the contagious disaster were being chased and attacked by “truth guards” for spreading rumors and misinformation. The bullying was so widespread that a user came up with a satirical guideline advising Wuhaners asking for help on Weibo to self-humiliate and apologize preemptively to the truth guards for their forgiveness.

Observers believed that the attackers were suffering from a paranoia of extreme aversion to others disseminating information that upends their orderly worldview. Wuhan’s distressed internet users were not the only group enduring abusive paranoia. Offline, in the real world, people from Wuhan and Hubei province suddenly found themselves unwelcome in their own motherland. Incidents of travelers from Hubei being rejected by hotels and residences began to emerge. By Jan 26, 3 days after the official seal-off, the spectacle had grown into a national concern, prompting bloggers to openly call for a calm-down of the frenzy: “Wuhan people are not our enemies.” More concretely, a plea went out to stop leaking the personal information of people from Hubei. Apparently, vigilantes in the system who had access to information such as hotel check-in registries were passing it on so that others could avoid, report, or drive away those associated with Hubei province.

As ordinary people were being chased, isolated, bullied, silenced and pushed around, the other line of questioning, after those responsible for the fiasco, was struggling to keep its focus. In a bombardment of outbreak-related information, public anger acted like the small ball in a roulette game. At any given moment it may land on top of the Wuhan Municipal Government, Hubei Provincial Government, the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the United States CDC, or the World Health Organization (WHO), depending on which media story or blog post was trending at that time. The outbreak and the Spring Festival holiday together created an unprecedented online time-space where hundreds of millions of Chinese, all off work, had nothing else to do but watching one of the country’s worst public health crises unfolding on their mobile phone screens. Every actor’s every action was scrutinized and commented upon by millions online. At one point, 10 million people were watching the live stream of the construction site of an emergency hospital, assigning nicknames to bulldozers and excavators.

In this environment, China’s ruling elites were all of a sudden thrown into a virtual colosseum where their politician skills were mercilessly tested. And they failed spectacularly. When municipal and provincial officials went on TV, they appeared detached, clumsy and outright stupid. In one of the much watched press conference, none of the three cadres, including the Hubei governor, could get their masks right. In a much condemned and ridiculed segment, the governor, responding to questions about the province’s mask production capacity, had to correct his answer twice after prompted by his secretary. The train wreck made observers wonder if Chinese bureaucrats, shielded off from media inquiry for too long, had completely lost the ability to even maintain the facade of competence. These were wholesale politicians never bothered to do retail.

Probably pressured by the public outcry to act more humanly, Zhou Xianwang, Wuhan’s mayor, later went on a one-on-one interview with CCTV’s Dong Qian off-script. To his credit, he answered a few questions with a level of candidness that’s rare in this shit show of government dysfunction. But the performance did not win him many scores. Rather, one of his answers hinted at a much deeper problem in the system. Responding to a key question about whether local authorities covered up the epidemic in the critical days before Jan 20, the mayor complained that as a municipal government, they need higher-level authorization to alert the public.

The admission on national TV started a nasty buck-passing game that would occupy public debate in a disorienting fashion for the next few days. Media seized upon the rare opening to dig into China’s epidemic control regime, revamped after SARS to prevent a repeat of the outbreak, hoping to pinpoint the source of any possible cover-up. But that line of inquiry was doomed not just because of the apparent “ceiling” of such investigation, but also because of the lack of basic ascertainable facts accessible by the public. Zhou’s interview injected a new level of confusion into the public debate. Caixin’s report depicted a picture of intertwined laws and regulations that were not clear whether it was the local governments or the national health authority who had the power to publish epidemic alerts. The Wuhan mayor’s argument seemed to have some legal ground: their obligation was to report infection cases upward, to the provincial, then National Health Commission.

Were health authorities responsible for suppressing life-saving early warning information, making the Wuhan government a victim, rather than perpetuator, of the cover-up? No one knew for sure. High level health officials dodged the question at a Jan 26 press conference. But people were piecing together fragmented information. Where facts were missing, narratives filled the gap. One of the unlikely sources of information were top medical journals. With impressive speed, Chinese researchers began to publish papers detailing the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of the novel coronavirus. Their published work filled some informational holes but left more questions unanswered. A key component of the emerging scientific literature on the virus that was eagerly consumed by the public were timelines. The studies published in journals such as Lancet and New England Journal of Medicine by top Chinese scientists, including senior officials at CDC, contained information of dates when infection cases were detected, onset of symptoms occurred and epidemiological actions were taken. The inclusion of many cases before Dec 31, when Wuhan authorities opened up the lid on the situation, gave the impression that CDC scientists were aware of the contagion before everybody else. Quickly, a narrative began to develop of CDC officials knowingly hide the information of human-to-human transmission. Worse, opinion leaders took aim at some of the scientists, including CDC Director Gao Fu, and asserted that they suppressed the information IN ORDER TO be the first ones publishing those data on top journals. Those accusations piled into a wave of indignation about cold-blooded academic profiteering, pressing CDC, and Director Gao Fu, to defend their work publicly, claiming that the analysis was done retrospectively. They got hold of December cases after they were released by local authorities in January.

Voices protecting CDC scientists argued that within the Chinese epidemic control system, CDC was the one institute, sitting under the NHC, that clearly didn’t have the authority to publish information about the disease. In a way, the scientists were circumventing disclosure restriction by sending out detailed information through Western academic journals. Critics of the Wuhan authorities also reminded people that even if their hands might have been bound by law when it comes to alerting the public, they nevertheless chose to actively silence those who took risk to send out early warnings. It turned out that the 8 Wuhan citizens censured in December for spreading “rumors” about the epidemic were doctors who alerted their colleagues and friends of the suspicious disease through WeChat. Wuhan government actively killed the canaries in its coal mine.

What’s ironic about the chastising of scientists for publishing papers is the fact that the scientific community is one of the brighter spots of the dark saga. If there is progress in the past 17 years, China’s increased research capabilities is definitely one. Chinese researchers completed the genomic sequencing of the virus in a matter of days and shared it with the rest of the world to allow for speedy development of diagnostic kits and techniques. It is worth noting that during the early stage of the SARS outbreak, Chinese scientists struggled and fought each other for months trying to identify the right pathogen.

Wuhan, in part, was saved from a much worse scenario thanks to that scientific competence. The sealed-off megacity was also kept afloat by an advanced network of internet-based service providers and mobile-organized support groups that were both non-existent 17 years ago. It was Alibaba’s online shopping platform, Didi’s mobile taxi hailing, SF’s courier services and Meituan’s food delivery system that kept the basic life-supporting functions of Wuhan operating when all its public services were either stopped or severely stretched. The contrast between those efficient and nimble providers of services and the bureaucratic apparatus couldn’t be clearer when an appalled public found out how their donation was handled

The Wuhan Red Cross Association, a government-affiliated body unrelated to the international Red Cross movement, won itself nationwide notoriety for its handling of millions of facial masks and other protection gears desperately needed by the battered hospitals on the frontline. The semi-government organization first attracted public attention when people noticed its 6% overhead charge on all donations, a not so high rate by international standard but eye-catching enough in an environment where trust of governmental philanthropies was generally low. When interested netizens dug deeper, they were aghast by what they saw: large amounts of much needed facial masks were channeled to dubious medical facilitieswhile frontline hospitals got almost nothing; doctors had to wait in lines at warehouses to pick up supplies for their colleagues while cadres casually carried away whole boxes of high-end masks; association staff using medieval methods to keep inventory of donated supplies, causing a huge problem of backlogging… To rub salt in the wound, the authorities prohibited all other channels of sending donations to hospitals, making Wuhan Red Cross Association the only game in town. Only after a country-wide outcry did the authorities softened the stance by allowing third parties connecting directly with some hospitals. And after the association opened up its warehouses to a private logistics company, the messy inventory was cleared up in a matter of hours.

If anything, Wuhan bankrupted the meritocracy myth for many people who once believed that the country was largely run by no-nonsense, result-oriented technocrats. Wuhan Red Cross Association reminded them how incompatible the country’s bureaucratic apparatus was to a lively society that was intrinsically good at practical problem-solving. Not only did the state and its organs unhelpful in such problem-solving, they were actively thwarting it. For a generation that grew up after the SARS outbreak, that experience was eye-opening, especially when they found that their self-organized fan clubs for idols were more efficient in delivering aid to the frontline than government bodies. It was no surprise that some of them wondered openly (and naively) if more accountable government officials could be generated through televised competitions just like their idols.

As this blog is being written, there is still no sign of the outbreak being under control. Hundreds have lost their lives and diagnosed cases are over ten thousand, while not a single senior official has been held accountable for the epidemic. There is a permeating sense of loss, for the diseased, but also for an era marked by its warmth and possibilities. As Li Haipeng wrote of the spring of 2003: “Officials at that time did not have to hide their personalities and could demonstrate their human side… From the outside, you could see the bureaucracy thinking, planning, maybe infighting, but almost certainly taking actions. You could feel that they at least had one consensus: that the society’s cries deserve a response.”

Courtesy: https://chublicopinion.com/2020/02/04/wuhan-a-tale-of-immune-system-failure-and-social-strength/amp/

One Reply to “WUHAN SYNDROME: THE INSIDE STORY OF THE CORONAVIRUS DOCTOR WHO WOULD NOT BE SILENCED”