ANDREA PLATE WRITES —

(This is the third in an original series about new wave feminist writers in Korea.)

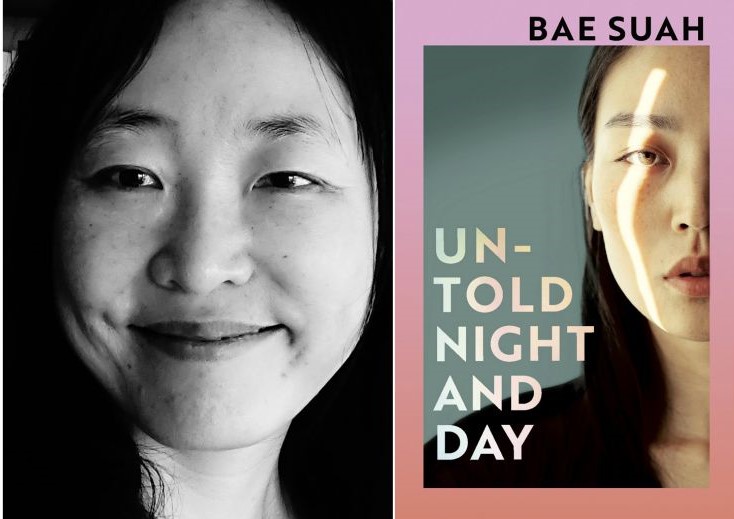

Why, for the past fifteen years, has literary icon Bae Suah — author of at least twelve sensationally popular surrealist novels, several short story collections, winner of two Korean literary prizes and a world-famous translator of other novelists — been called, by some critics, “un-Korean?”

The brouhaha began in 2005, when a reviewer wrote that Suah’s novel, A Greater Music, “does violence to the language.” (Note that, similarly, Japanese master stylist Haruki Murakami has been dubbed “un-Japanese” by his country’s literary establishment).

Untold Night and Day (Abrams, The Overlook Press), Suah’s edgy and electrifying 2013 novel, has come to America this year, thanks to Deborah Smith, a world-famous translator (and winner of the Man Booker prize for her iteration of Han Kang’s acclaimed 2017 novel The Vegetarian).

On the surface, Untold Night and Day is about a seemingly interminable night, and day, in the life of 28-year-old Ayami, a mixed-up millennial, law school drop-out and unaspiring actress. The story starts with Ayami’s last day of work— at a Seoul audio theater for the blind (so this is no humdrum coming of age tale). The newly unemployed Ayami wanders the steamy streets of Seoul during a long, hot night, while her mind wanders, too— through intricate, esoteric, other-worldly channels of communication shared, improbably, with her German language teacher and a visiting poet. Topics range from food to love to work to … the meaning of life (whatever that may be).

Any reader expecting anything remotely resembling an answer to that question will be disappointed. Suah’s writing — in both style and substance — is determinedly esoteric. Like her other groundbreaking novels, Untold Night and Day is akin to neither old-school, mainstream Korean literature (with its themes of patriarchy, family, motherhood), nor popular contemporary troves (focused on feminism, women’s rights, male violence). As her narrator says: “I am emotion.”

Is it even a novel? Untold Night and Day is more like a prose poem –150 pages of fantastical, phantasmagoric images showing just why Suah’s writing style has been labeled, in addition to un-Korean, as surrealist (revelatory of the unconscious mind); Dadaist (using absurdity and humor to express protest); shamanist (tying the spirit world to the physical world); and “Lynchian” (as in director David Lynch’s macabre, surrealist movie “Blue Velvet,” which opens with a shot of a severed ear.) We must add, too, a comparison to Jackson Pollock, the American abstract expressionist who hurled paint onto empty canvasses, ostensibly to “see” shapes and images from all angles.

Suah hurls herself away from virtually all literary conventions, universally —not just those specific to Korea. She couldn’t care less about consistent tenses; a linear timeframe; a narrative arc; realistic characters; simple sentences; and concise thought. Unabashedly, the ever-unapologetic Suah admits that she prefers “a story that goes in reverse order.”

She also prefers long sentences to the short ones favored by Korean authors; witness this from her latest translated work: “The candle left out on the windowsill had melted without ever having been lit; the wax collapsed pathetically under the sun’s fierce rays, its shape suggesting the peculiar way love concludes.” In addition, she relishes rather than rejects repetition: various characters’ faces are “pockmarked;” radio voices crackle on and off, inexplicably; darkness and blindness are everywhere— at an airport blackout; a theater for the blind; a restaurant with blind waiters; a woman who finds that “pitch-black darkness smothered her vision as though Indian ink was poured over her eyes.”

Identical passages pop up repeatedly throughout this novel. A skirt “flops like an old dishcloth” many times; eye sockets “like sunken caves” appear on multiple faces. Suah’s style is not to hammer her images, but to sneak them into the subterranean reaches of the reader’s mind, lacing them so deftly, so stylishly, so strategically throughout this saga that they come to feel more comfortably familiar than redundant.

Perhaps the only recognizable literary anchor in this tempestuous sea of surrealism is her heroine Ayami. Despite the young woman’s desperate circumstances — unemployment, aimlessness, disaffection from society — she is strong and determined, not unlike Virginia Woolf’s Clarissa Dalloway or Flaubert’s Emma Bovary (until the latter crashes and burns). Strong female characters populate all of Suah’s novels.

“They are women who refuse or cannot have their own place in traditional society,” explains Suah. “I love such women. Women who cannot be guaranteed social status through marriage, or women who refuse to marry in order to obtain it; women who do not suppress themselves for the sake of their parents or siblings; women who, as a result of their independent personalities, are lonely and financially precarious. Women who go their own way in accordance with their own stubbornness, and who are not afraid to do so.”

Yes, she likes women like herself. Suah loves defiance. It comes to her naturally, and easily. She never studied literature (majoring instead in chemistry). She splits her time between Korea and Germany. She translates German texts into Korean, including some by Kafka. She never intended to become a writer, or so she says; “I was practicing my typing and that was when I wrote my first story. It was an accident.”

An accident waiting to happen, perhaps, to a girl who grew up in a divided Korea; a girl taught to see “the Other” as the enemy. Suah, now 55, detests borders and boundaries of all kinds—political, geographical, literary. In the universe of her dreams, opposites are non-binary. “Night and day exist simultaneously,” she writes. People are “ghosts” whose bodies provide “a passageway” from one to another.” North and South, then, would be one. So, is Bae Suah un-Korean? No, says translator Smith, who perhaps knows the author and her work best. “She is a decidedly ‘non-national’ writer.” Or, as Suah explains further: “A story is like the universe…unlimited, simultaneous and open.”

Critics should be cheering, rather than condemning, Suah’s wildly hopeful worldview and the imaginative literary tools behind its creation. A little un-Koreanness in adept Korean hands can go a long way.

Andrea Plate, Asia Media International’s senior advisor for writing and editing, has degrees in English Literature, Communications-Journalism and Social Welfare/Public Policy from UC Berkeley, USC and UCLA. Her college teaching experience includes Fordham University and Loyola Marymount University. Her most recent book, MADNESS: In the Trenches of America’s Troubled Department of Veterans Affairs, about her years as a senior social worker at the U.S. Veterans Administration, was recently published in Asia and North America by Marshall Cavendish Asia International.