(This is the fourth in an original series about new wave feminist writers in Korea whose work has started to reach English language readers via superb translations.)

ANDREA PLATE WRITES — “Fitting into middle class society is getting harder and harder for the younger generation.”

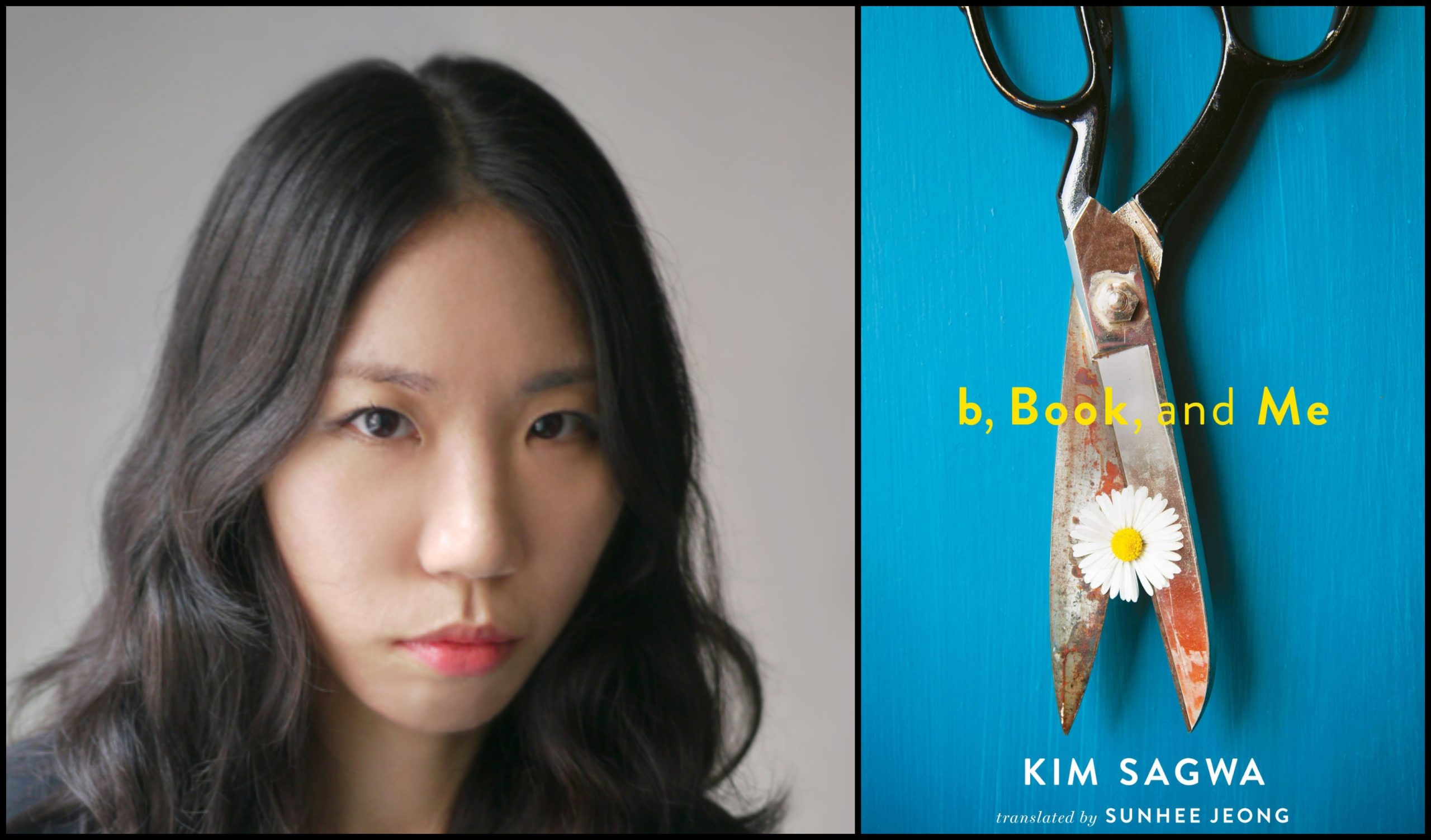

So says Kim Sagwa, author of four acclaimed novels and two short story collections, who knows something about adolescent angst. This pre-eminent South Korean literary star, dubbed by some the voice of a generation, was once a high-school drop-out.

For all her adult success, Kim Sagwa, now 36, who graduated in 2009 from the Korean National University of the Arts, cannot, and will not, abandon the theme of adolescent angst. This is the heart and tortured soul of her curiously titled 2011 novel ‘b, Book and Me’, just translated into English early this year by Sunjhee Jeong (Two Lines Press, in arrangement with Changbi Publishers, Inc.). It is also the theme of her 2008 novel Mina, featuring two young girls who feel trapped, not by poverty but by their parents’ wealth and rigid value systems.

‘b, Book and Me’ follows three protagonists down the gangplank of adolescence to adulthood:

Rang (the narrator, a/k/a “me”) lives in a provincial coastal town she disparages as a dime store Seoul: “People bought cars from Seoul Motors and ate at Seoul Kitchen…the more it imitated Seoul, the more it became … not Seoul and foolish.” She is brutally bullied by boys at school and feels neglected by a mom and dad who “didn’t care” about her grades, good or bad, because at home they were either “busy with other stuff” or asleep. It’s a town that winners leave, losers stay, and teens are … stuck.

The character “b” (no typo here- the lower- case letter signals how little this girl thinks of herself) is a poor teenager from a poor part of town whose father works in a factory. “Dreams are expensive, which is why I can’t have one,” she says. b has no friends and no friendly or approving teachers. She lets boys stroke her breasts “like a dog,” since it’s the closest she can come to affection. Worse, her terminally ill sister means that “my life will always suck.” Reader, beware: b is not bad! She’s poor. She’s suffering. She loved her sister, until the family couldn’t afford to pay for medical care. “If I had a billion won,” she imagines, “my sister wouldn’t die.”

Book hides out in a forest, with books. Kicked out of school (and perhaps out of town), he reads all day, every day. He likens himself to a man in a painting he likes depicted trying to climb down a kitchen sink drain. Book wants “to go in and never come out” of books. Book wants to be a book. Who needs the material world when you have books?

These are Korean teenagers, trapped in a country still technically at war with the North, with one of the highest suicide rates in the world and a long-held cultural distrust of mental health treatment. Not by coincidence is the sign on the mental hospital — make that, “metal hospital” — missing an “n.” But this story, while set in Seoul, could take place anywhere in the world where teens feel the fallout of high divorce rates, high unemployment rates and a sharp societal divide between rich and poor. Says author Sagwa: “I’ve been realizing that there is a very similar kind of social pressure everywhere, even outside of South Korea.”

Sagwa’s style mirrors, even embodies, the surrealistic, bewildering, ghastly and ghostly quality of adolescence itself. She writes in short, staccato sentences but otherwise emulates master South Korean surrealists such as famed author Bae Suah (Untold Night and Day). Places and characters are symbols: A popular teen café is named Alone; an impoverished, ruinous neighborhood is called The End; an ever-studious, workbook-toting student is named Glasses. Add to that surrealist imagery: Rang sees the blue ocean as “a white field of snow. Winter tumbling over the ground;” unusual linguistic formulations: “not -poor Rang;” and repetition to reinforce images: “The [school]bell rang again. The bell rang again. The bell rang again” — echoes of high school hell, where loud bells slice through hourly time like a metronome.

Fortunately, b, Book and Rang grow up, although the adulthood they attain is inglorious. “There was no miracle,” remarks Rang. “The only thing left to do was turn into an adult.” Fortunately, too, time has a way of untwisting things, if not healing them: b’s sister gets a proper burial. Subsequently b gets to move out of town to start life afresh. Rang escapes her anger, which “grew smaller and eventually disappeared.” Only Book seems stuck in the past. “I just want to read,” he says, last seen undergoing police interrogation for some unspecified “crime” (like excessive reading).

Obviously, this is no commonplace coming-of-age tale. b, Book and Rang face far bigger foes than the adult “phonies” decried by Holden Caulfield in J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye. Their problems, the author believes, represent “a systemic issue, not a personal one. Globalization means simply Americanization. The global free market, in reality, is built on the absolute belief in the U.S. dollar. In this free market world, everything and everyone is measured by that metric.”

Take that, America. No wonder critics consider her “fierce.” This slim,134-paged novel is an easy read but it packs a remarkably hard political punch. Who would have imagined, nine years ago as she wrote the book, that the world would be ravaged by a deadly pandemic and civil unrest? Kim Sagwa is more than a gifted writer. She is prophetic. One might well wonder, if not worry, what dystopian future she may conjure up next.

Andrea Plate, Asia Media International’s senior advisor for writing and editing, has degrees in English Literature, Communications-Journalism and Social Welfare/Public Policy from UC Berkeley, USC and UCLA. Her college teaching experience includes Fordham University and Loyola Marymount University. Her most recent book, MADNESS: In the Trenches of America’s Troubled Department of Veterans Affairs, about her years as a senior social worker at the U.S. Veterans Administration, was recently published in Asia and North America by Marshall Cavendish Asia International.