TOM PLATE WRITES — A new report from a respected US think tank at least tries for a fair and sensible analysis of the China challenge. For this alone, given the almost rancid mood in the US about China these days, President Xi Jinping and his government are not going to get a fairer shake from America’s political-military establishment than the RAND Corporation’s China’s Quest for Global Supremacy.

This is the background: last week, at the G7 talkathon (core members: the US, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan and the host, Britain), US President Joe Biden went on and on about China as a global threat, human-rights violator, etc – the familiar anti-China litany that the Trump administration hyped and now Biden’s foreign policy team is seeking to carry forward.

Alas, this unctuous display of rectitude takes me back to 1994 when first-term US president Bill Clinton put Warren Christopher on a jet to Beijing to offer a finger-wagging lecture but the Chinese would have none of it – they pointed the hapless secretary of state towards the airport, sending him home embarrassingly ahead of schedule.

There’s no reason to believe that Xi will be any more receptive to Western sermonising, sincere or not. But Biden’s gambit to look as tough as Trump might well backfire. The fact is that not all G7 members are gung-ho over the moralism.

Backing itself into a policy corner with its own stale thinking, Washington at some point will need to reel out a more cosmopolitan line if it wants to keep the “good guys” together.

This is where the RAND report helps. It takes a holistic view of the China question and offers a subtle lifeline that might help the US with its China obsession.

The report’s authors, Timothy R. Heath, Derek Grossman and Asha Clark, avoid any notion of China as the second coming of Confucius (disguised as an aircraft carrier) but insist on the crucial distinction between what the Chinese truly desire, and what the US imagines that to be.

In its final pages, they remind the reader of “the importance of the Chinese dream as an end point for all strategy and policy”, adding that “any posited strategy for US competition … should be nested within the broader strategy to achieve national rejuvenation”. In other words, before anything else, China is out for itself, not out to get the US.

Beijing knows it still has a long way to go and has little time for World War III in the Pacific. The US, the superpower leader of global capitalism, is anything but dead yet.

The RAND report states: “China’s ability to overtake the United States by a decisive margin is doubtful. Despite enjoying faster growth than the United States in past decades, China is well into an economic deceleration.”

Even if the Chinese economy rebounds brilliantly, the RAND analysts suggest that taking on the US directly would prove tough to sustain: “A principal risk is that a Beijing desperate to gain an edge by weakening the United States in some manner may drive relations into open hostility, dramatically increasing the prospect of conflict.”

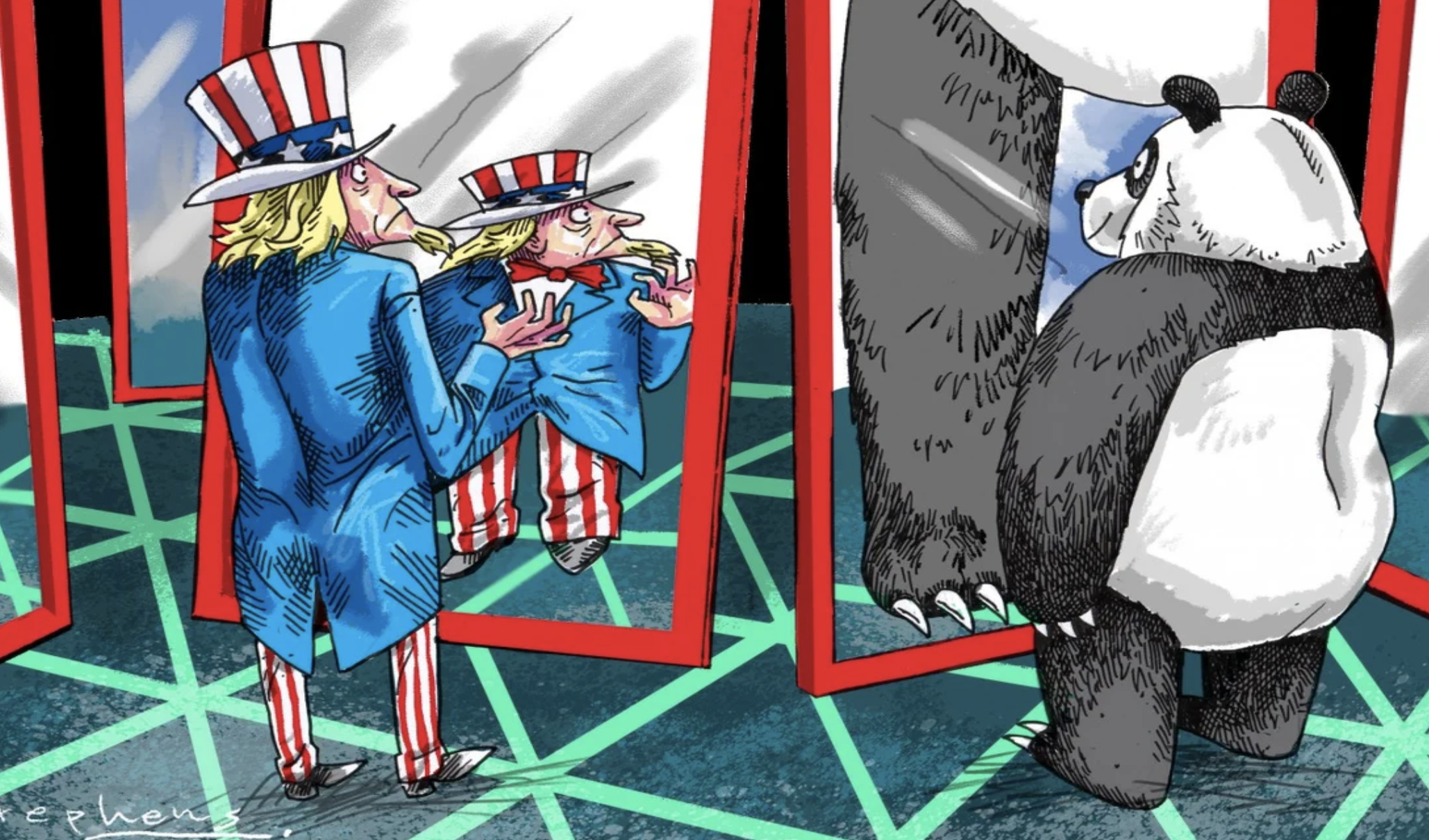

Even the most cunning wolf-warrior would be biting off more than it can realistically chew trying to eat Uncle Sam’s lunch.

It’s much the same for the US: better for both sides to “be like water” (recycling Bruce Lee) and work around the potential war issues. The RAND report advised: “To control risks, both sides may find it imperative to seek out ways of stabilising the competition, perhaps in part through senior-level engagements and other cooperative endeavours.”

Today’s RAND, although often Pentagon-funded, is serious about its social-science methodology and abhors purely magical (or PR) thinking. This is a trait you can admire even if you’re no fan of its funders.

None of what the RAND report proposes will come cheap. Its authors admit that the US defence department “may need to invest in maintaining a significant presence in the Middle East and Africa to complement the competition in the Indo-Pacific”.

But what about America’s battered infrastructure, shameful schools and low-income housing crisis, and the need to allocate resources to deal with them? “The derivation of a Chinese strategy can, hopefully, provide a useful tool for that important task,” said the report.

That’s a quaint way of saying: let’s keep the China challenge in proportion and not go off the deep expenditure end because, after all, “which side can build the more technologically innovative and prosperous economy, flourishing and well-governed society, and durable and responsive politics will likely be the side to gain a decisive advantage in competition”.

To be sure, no RAND report would ever rush to conclude that going all-out against China while also attending to a massive domestic revival might well prove beyond the national pocketbook. Nor would Xi’s think tank experts either, we presume. But my view is that indeed it would: find another way.

LMU Professor Tom Plate is also vice-president of the Pacific Century Institute. He is the author of “Conversations with Lee Kuan Yew”, in the Giants of Asia series, among other books.