ELLA KELLEHER WRITES – “We can’t know what happens behind closed doors” is a frustrating and insidious phrase that is too often weaponized to reduce instances of sexual assault to minor misunderstandings. In Japan, if a sexual assault occurs in a space without any witnesses, the case becomes a “black box” – a place that the local police departments choose not to investigate. Author, journalist, and filmmaker, Shiori Ito, found herself in that void. One where the overwhelming vacuum of darkness could have swallowed her whole and silenced her like countless other victims had she not battled to unveil one of Japan’s largest judicial and social issues.

In Japan, the #MeToo movement has been adapted by survivors of sexual assault to #WeToo in an effort to overcome the anxiety which surrounds standing out and “to demonstrate that, as members of society, these problems concern all of us.” In a highly collectivist culture, deliberately bringing attention to oneself, especially regarding something as appalling as sexual violence, is severely looked down upon. This daunting social reality is precisely why Shiori Ito has been and continues to be an incredible inspiration for survivors of sexual assault. Not only did she choose to stand out and speak on behalf of suppressed victims, she did so without hiding her face or her name.

In 2017, Ito held a public press conference in Tokyo that surrounded a rape that Ito reported which the Japanese authorities deemed to be “nonprosecutable.” Since the assault took place in a private room, where the cameras of the hotel could not observe, the case was considered a “black box.” Not only was Ito left with the impossible task of single-handedly patching together the missing pieces of the situation, but she was also expected to assemble the scattered shards of her psyche after such a traumatizing experience.

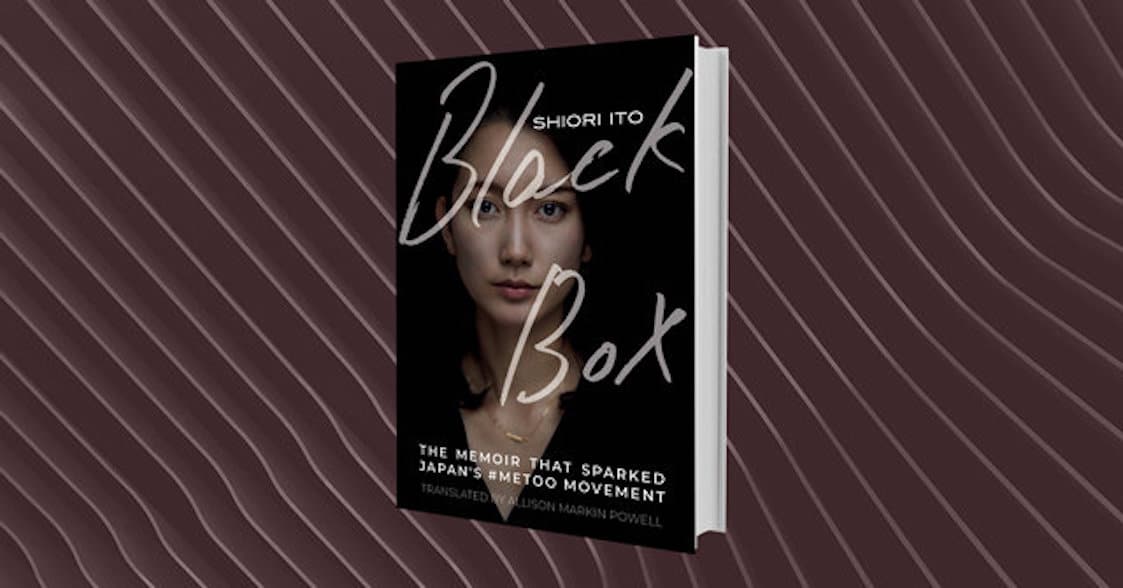

Black Box (2021) is as eye-opening and informative as it is gut-wrenchingly evocative in its narrative. This is made even more palpable by the skillful translator, Allison Markin Powell. One of Ito’s primary goals in this story is to dispel Japanese society’s mythos surrounding sexual assault. Instead of society stereotyping rape as a situation in which a woman is violently assaulted in a “dark alley,” Ito asserts that the reality of sexual assault wildly varies. Assaults by acquaintances make up for 88.9% of Japan’s reported rapes. In the United States, the numbers are almost identical, as 8 out of 10 reported assaults are conducted by those the victims know personally. Ito posits the idea that instead of only being wary of dimly lit corridors and seedy alleyways, we must also acknowledge that the danger can lie closer than expected.

Following her adventurous nature, Ito found herself in New York City in 2013 – a brilliant and young aspiring journalist doing what anyone would, networking to scale up the professional ladder. She meets Noriyuki Yamaguchi, the Washington Bureau chief of the Tokyo Broadcasting System (TBS). Ito crosses Yamaguchi’s path in the workplace, a space that many victims encounter their future attackers. When Yamaguchi learns of Ito’s career goals, he offers his connections and professional support. Through exchanging emails, which the book displays in their entirety, Yamaguchi repeatedly promises to secure Ito a position as a producer at TBS.

The pair met again two years later to discuss Ito’s ascension in the world of journalism in Ebisu, a hip Tokyo neighborhood. Ito arrived with the reasonable presumption that others besides Yamaguchi would also be present – the so-called “producer connections” he promised her. As night fell on April 23rd 2015, Ito and Yamaguchi walked from a train station to a local kushiyaki bar. Despite the cozy setting, Ito found herself in the metaphorical lion’s den. She writes that “no one else [was] there waiting for us, and in the back of my mind, I was surprised that it was just us two.” Unbeknownst to her, Yamaguchi would drug her drinks and take her to the Sheraton Miyako Hotel, only for her to wake up as he is brutalizing her.

In possibly the most haunting and infuriating moment, Ito details how when she demanded her clothing back, Yamaguchi used the moment to look down upon the bloody and distraught Ito and say, “Before, you seemed like a strong, capable woman, but now you’re like a troubled child. It’s adorable.” Ito includes this belittling comment to reveal the devastating impact of rape: it takes away physical autonomy and control from an individual – effectively killing a person without needing to murder them.

The destruction that an assault creates can persist long after the actual rape takes place. After her attack, Ito was plagued by night terrors, severe anxiety, depression, and PTSD, while also needing to face the corrupt Japanese police force that would rather protect an important chief of TBS than an innocent victim of sexual assault. Despite the “black box” operating like a social sarcophagus, Ito took it upon herself to publicly appear at press conferences, on TV, and even documentaries. Ito decided that in order to validate the many other victims of rape whose stories have been quieted, she must make her experience known instead of remaining anonymous. Without having their trauma acknowledged, survivors become trapped by their own mental entombment, destined to be the forgotten ghosts of patriarchal societies.

After years of sparring with the Japanese legal system, in 2019, Ito finally succeeded. She explains that “the decision in my two-year-long civil trial for [rape] was announced. I won the case, and the decision acknowledged that ‘there had not been consent.’” Ito follows this triumphant sentence by explaining her motive for writing Black Box: “If, as in many Western countries, sexual intercourse without consent was routinely prohibited in criminal law, and I had found redress, then perhaps I wouldn’t have gone to the length of writing this book.” This book is her healing process, and we readers are her witnesses.

Years after the assault, numerous press conferences, and the court verdict, Ito’s resounding mission proves to be as brave and powerful as her single-handed clash against the seemingly impenetrable Japanese legal system. “I want to continue to make things visible, to bring them into the light. Because that’s how they will change,” writes Ito as the final note in her book.

Black Box humanizes the dehumanized through the power of its translation. As Ito explains, there are no Japanese “[words] for a woman to use in protest that puts her on equal footing with a man who is her superior.” Powell’s translation wields the English language’s lack of hierarchical rhetoric to grant female survivors of sexual assault equal footing with their attackers. Survivors are no longer forced to act as sexualized, weakened victims hiding behind their “timidness.” Ito gives us readers her story, trauma, and her ultimate victory in a way that challenges the status quo and seeks empowerment rather than pity. She proves that there is light, even within the sinister darkness of the “black box.”

LMU English major graduate Ella Kelleher is the book review editor-in-chief and a contributing staff writer for Asia Media International. She majored in English with a concentration in multi-ethnic literature

Very powerful thank you for sharing this wonderful review