BRIANNA HIRAMI WRITES — Historians often skip over the pain that war leaves on the countless hearts of those who have lost their loved ones to senseless violence. Whether it is a soldier caught on the battlefield, a parent praying for their drafted child, or a refugee actively escaping a warzone, we can all agree that war is one of the most dehumanizing and heart-wrenching experiences to endure. For the families who try to escape the violence, life can feel like Hell when they are forced to leave everything behind. How is it possible to overcome these traumas and live for a purpose when everything has been so abruptly stripped away?

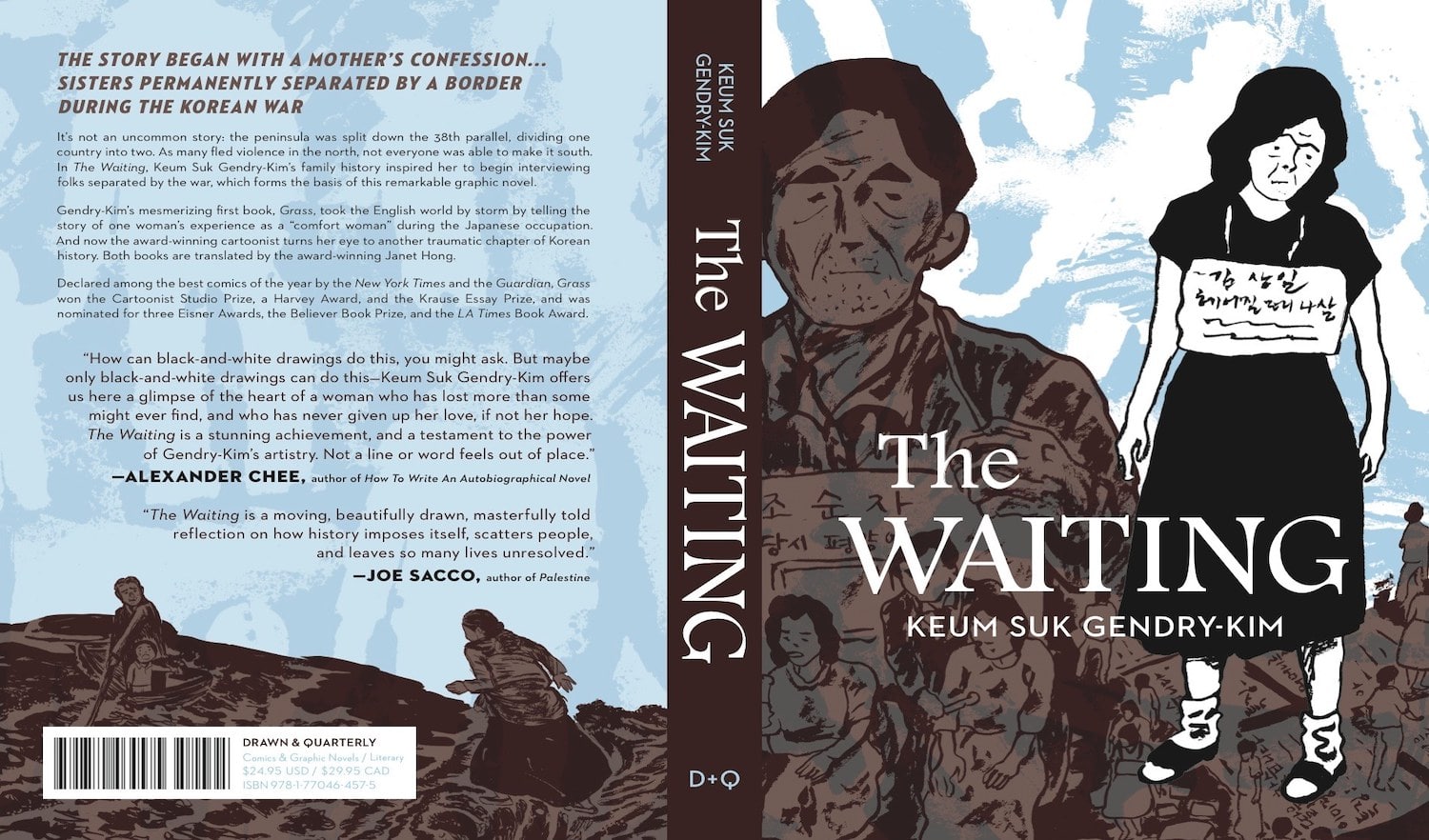

Keum Suk Gendry-Kim’s graphic novel, The Waiting (2021), is a fictional tale based on her mother’s experiences as a refugee in the Korean War. In her fictional narrative, Jina’s mother, Gwija, narrates her terrifying account of fleeing North Korea and being separated from her husband and son while taking care of her infant daughter. As the Soviet Union and China invade South Korea, Gwija and her husband make the difficult decision of leaving their home in the North to face the dangers of migrating to South Korea in hopes of taking refuge there.

Keum Suk Gendry-Kim is known for her beautiful graphic novels that flawlessly use simple pictures and language to convey the strong emotions of her characters. Her other graphic novel, Grass (2019), also translated into English, won the Krause Essay Prize, Cartoonist Studio Prize, and the Harvey Award. The translator for this graphic novel, Janet Hong, expertly conveys this masterpiece and forces a deep emotional response its audience. Hong is a translator based in Vancouver, Canada, and has won the TA First Translation Prize for her other translated work, The Impossible Fairy Tale.

The Waiting opens with Gwija’s daughter, Jina, moving an hour away from the city where she and her mother reside. Before she moves, her mother asks her to call the Red Cross Center and ask them again if they have heard any updates on her son, Sang-il. Jina admits that life’s craziness has put finding her brother at the bottom of her priorities list, but her mother still continuously asks her if she’s heard any news on the brother she’s never met before. Despite her failure to find her brother, her mother never gives up hope on the possibility of reuniting with her son.

The novel then shifts to Gwija’s childhood in the North and how she was treated poorly compared to her brothers. There was never enough food for everyone to be full in her household, but her brothers always got the better pieces of meat and white rice while she was stuck eating the leftovers. Even though both of her brothers attended school, she was forbidden from going to school because society deemed it inappropriate. She narrates how one of her brothers got drafted into the war and died from a bomb explosion as she grew up. Gwija’s mom warned that even women were getting drafted into the war, and the safest option was to get married and have children. Gwija was then forced into an arranged marriage with a complete stranger and had two children with her husband.

As the war raged on, the family was told that their best option was to flee to South Korea and seek safety there. During their harrowing journey to South Korea, Gwija’s family was constantly surrounded by other North Koreans trying to find safety in the South. Amongst all the pushing and shoving, she tells her husband that their baby daughter, Minhye, needed to be fed and changed immediately. She tells him to stay where he is and that she will return to him quickly. However, after she feeds and changes Minhye, she sees that her son and husband have mysteriously disappeared. She cries out for them in an absolute panic and even waits for them in the next town. They are nowhere to be seen.

The Waiting – 247 pages – Drawn and Quarterly – $16.99

Gwija realizes that she must continue the journey without her family and boards a cargo train that takes her and Minhye safely to South Korea. There, she works to provide for herself and Minhye and eventually marries another man, giving birth to two children with him. However, she can never forget the family that she left behind in North Korea and constantly reminisces about her son.

During a time where COVID-19 has driven families apart and has caused FaceTime to be the most practical option for being connected to your loved ones, it is almost too painful to imagine losing your entire family unexpectantly. The violent drop in Gwija’s stomach after realizing that she was all alone, with only her baby tied to her back, is just one of the reasons why war is so evil. The isolation from human life, the last look in your loved one’s eyes, the haunting ringing after an explosion. The only strength that remained in Gwija was her child and the hope of seeing her family and embracing them once again. Family, it seems, is the pillar of stability that keeps thousands of other refugees alive in body and spirit, inspiring them toward safety and prosperity.

Book reviewer Brianna Hirami is a recent graduate of Loyola Marymount University with a major in English and a minor in Asian and Pacific Studies. Brianna will attend LMU again to receive her Literature Masters.

Edited by book review editor-in-chief, Ella Kelleher.