ANGELINE KEK WRITES — There is a truth about the human experience that helps those of us who have embraced its lessons to walk around with an easier spring in our steps — the understanding that we are products of our pasts. Every thought, every choice, every path chosen big or small, tapers from the experiences of our malleable childhood. This comprehension is heavily built upon in the field of psychology, an example being attachment theory. In short, “[attachment theory] correlates our feelings, thoughts, beliefs, and what we expect in life as adults to the way we attach to our primary caregivers as infants” (Impellizeri).

Humans start developing patterns and assumptions the moment we are born in order to survive. These patterns are deeply ingrained in our subconscious, directing our behaviors in ways we might find puzzling if the patterns are left unexamined. Have you ever felt bubbling anger at a passing word from a friend, only to feel ashamed afterward? Have you ever surprised yourself by bursting into tears watching an innocent video of an adorable moment? There is a deeper layer to peel back in these seemingly irrational reactions.

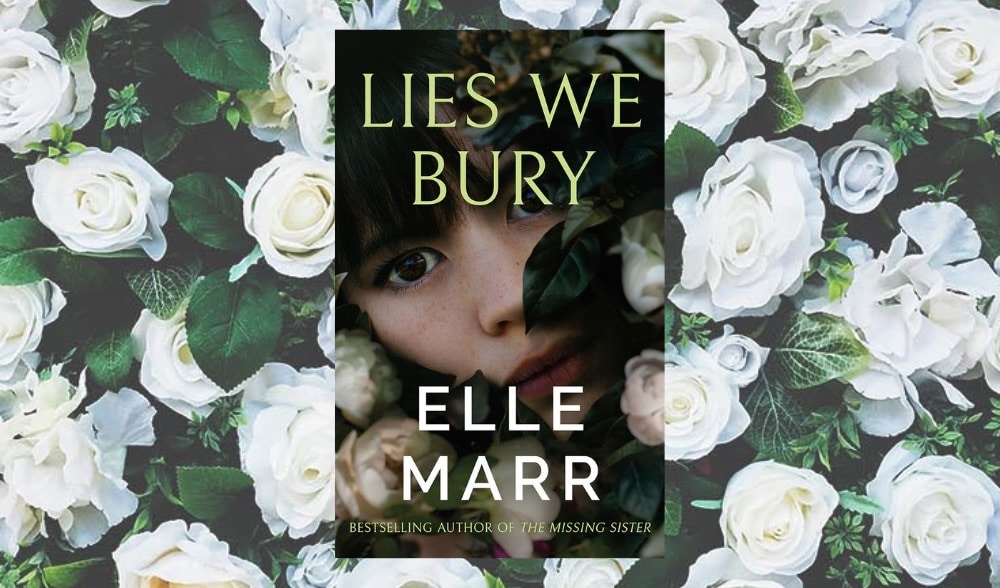

Elle Marr is a Chinese American author who thoroughly appreciates and acknowledges the importance of behavioral patterns. Her second published work, Lies We Bury (2021), is a twisting murder mystery that revolves around Marissa Mo, a bunker-captive survivor. Born inside a basement in a small community of kidnapped women and two other basement-born children, Marissa never saw sunlight until nearly a decade into her life. As a 27-year-old, Marissa now goes by “Claire Lou,” a photographer in Portland determined to keep her past in a tightly locked vault.

Marissa’s plan to stay low begins to unravel when she is offered a job as a crime photographer for the Portland Post. This was supposed to be her big break — until anonymous notes from a killer with clues to their subsequent murders started finding their way to Marissa, alongside relics from her subterranean childhood at the crime scenes. Who could possibly know these personal details from her past except for her captor, Chet, scheduled to soon be released after 20 years of prison?

Determined to keep her job, Marissa makes a pact with the devil: if she could solve the bloodthirsty riddles, she can prevent the next murders and still make next month’s rent. Desperate for someone who could understand the madness that has rudely invited itself into her life, Marissa shows up at Jenessa’s doorsteps, one of her half-sisters whom she has not seen in two years. Even though Marissa, Jenessa, and Lily spent years locked up in the same room, their journeys into the outside could not have been more different. “While [Marissa] acted out in [her] own private ways and Jenessa engaged in more public forms of self-harm, Lily exercised her angst in earth-friendly, artistic behaviors: painting, sculpting, writing poetry, and protesting industrial practices with hunger strikes.”

Jenessa’s drug addiction has been a juicy ordeal for the nosy public, whose relentless curiosity has only amped up in anticipation of Chet’s release. Over the years, there has not been a shortage of overly zealous devotees. The public’s prying fervor knows no bounds: aging childhood pictures to speculate the captives’ current appearance, showing up at their doorsteps with pleas of compassion and friendship, even offers of topless modeling from tabloids.

No stranger to how insatiable people can be, Jenessa advises Marissa to keep her nose out of it, attributing the notes to journalists trying to rile them up in time for the anniversary. Marissa knows better: “I glance down at the page, wanting to believe. But the police didn’t learn about the body until the next day.” Whoever wrote the notes orchestrated the gruesome murders.

As Marissa continues the twisted treasure hunt, she finds more than dead bodies in freezers and tunnels. The killer(s), whoever they are, knows how to bring out parts of Marissa she does not want to face — the parts of her that she wants to stay buried in the basement, parts of herself that reminds her of Chet, of the fact that she is related to him no matter what she does. “I’m no better than Chet when he would snap and begin beating Rosemary. The anger issues I’ve worked haphazardly to subdue, the rage that percolates beneath my skin and marks me as Chet’s perverse offspring, align exactly with what people think of me—that I’m damaged. A wild animal.”

Slowly, then all at once, it clicks: Marissa has been hiding for so long, trying to stay low, creating Claire in the name of barely surviving. She might have escaped the bunker, but she is still living in hiding. If she wants to live genuinely, she must face her past — this shadow of a murderer gives her no choice. She must dig deeper than she has ever before.

Armed with no real clue as to whom the note writer could be, Marissa traces her way back to the people who all had stakes in her origin story: her family, her captor, past stalkers. Narratives of the present are interlaced by chapters of time passed, written from the perspective of adolescent Marissa as she uncovers memories, connections, resentment, and hidden motives.

As the shadows engulf everything else, one truth comes to light: knowing that we are products of the cards we have been dealt might seem like a prison, but the knowledge that what matters is how we choose to play these hands is as freeing as it gets. “When I think life might be going my way, the past isn’t through with me yet.”

Angeline Kek is a book reviewer and contributing staff writer for Asia Media International. As a recent graduate from LMU, she majored in English with a concentration in poetry and creative writing. She is interested in poetry and writings that are unhesitatingly honest.

Edited by book review editor-in-chief, Ella Kelleher