BOOK REVIEW EDITOR-IN-CHIEF ELLA KELLEHER WRITES – “The sky is about to fall. Where do you go?”

To be a child is to imagine a world made of glass. All your romanticized beliefs about your country and its people are contained within one fragile crystal sphere that can fracture at any moment. Ginny Park, a teenage Zainichi Korean (Japan-born), is forced to come of age under the crushing weight of reality and the horrors of xenophobia, politics, and ethnic violence. Torn between her Korean heritage, her Japanese birthright, and her evolving contempt for both nations’ sociopolitical climates, she must make a fateful choice. Either bow down and lose her voice in the process or challenge the status quo and face the devastating consequences.

The year is 2003, and Ginny is in picturesque Oregon. She is about to get expelled from school yet again at the tumultuous age of seventeen. Stepmother Stephanie, a talented picture book author who took Ginny into her home after being kicked out of school in Hawaii, is not livid in the way one would assume. Instead, she is troubled by the root cause of her daughter’s disassociation from school and youth culture altogether. Stephanie cannot pry open the tightly shut lid on Ginny’s heart. Even Ginny herself has not begun the process of reckoning with her past trauma. What prompted her to leave her native Japan so suddenly? Through journaling her past experiences, she begins to uncover painful repressed memories.

It was that infamous day that North Korea launched a missile towards the direction of Japan. Detonating into the East Sea, the weapon’s resonating tremors triggered a wave of ethnic-based contempt in Japanese society that lay dormant years after the Japanese invasion of Korea. As a Japanese-born Korean, Ginny was sent to a Korean academy where the girls wore chima jeogori – a beautiful piece of traditional Korean clothing and a way to paint a target on oneself.

One day Ginny decides to skip class and venture into an arcade not long after the missile test, where she meets a gang of “police officers” who corner her. “You Koreans are dirty things, aren’t you?” one of the men asked wickedly. Ginny was used to being teased by her Korean classmates for her inability to speak Korean and her general ignorance of her native culture, but being singled out by Japanese people was a painful first. “You have pretty skin, but what about your soul?” the other man questioned. Beautiful and dirty: the dichotomy placed upon Koreans by the Japanese that harkens back to the darkest times of Japan’s colonial hegemony over the peninsula. Ginny was simply a toy to these men, a “doll that [they] could do with as [they] pleased.” She knew she could not beat them. However, remaining silent was no longer an option, not even if it meant being assaulted.

The despicable trauma of sexual violence prompted wild speculation in Ginny’s delicate teenage mind. There could only be one culprit for such a cruel crime: the Kim regime. Yes, in Ginny’s eyes, the repulsive North Korean dictatorship was to blame, and she began to suspect the concept of nationalism was a crime in itself. “National borders [are] nothing but graffiti. Why did I have to suffer like this because of someone else’s graffiti?”

And so, a young “revolutionary in training” was born through the viciousness of ethnic-based assault. While grown-ups may be at the mercy of their careers, institutions, and governments, the young often feel they have nothing to lose. If Ginny could show her school (which was sponsored by the North Korean government) that the Kim family was not untouchable, that they were fragile and at the mercy of their own people, she would have accomplished a feat far beyond her perceived abilities. The Kim family, which the North Korean people hail as gods upholding the sky itself, are as breakable as any other person. Their pictures have no place in schools. In a moment of concentrated rage, Ginny destroys a portrait of Kim Il Sung on the school wall. Her naïve, innocent worldview shatters like the glass frame of the dear leader. In a glittering array of thousands of tiny shards of glass, at last, “Kim Il Sung was revealed to be human.”

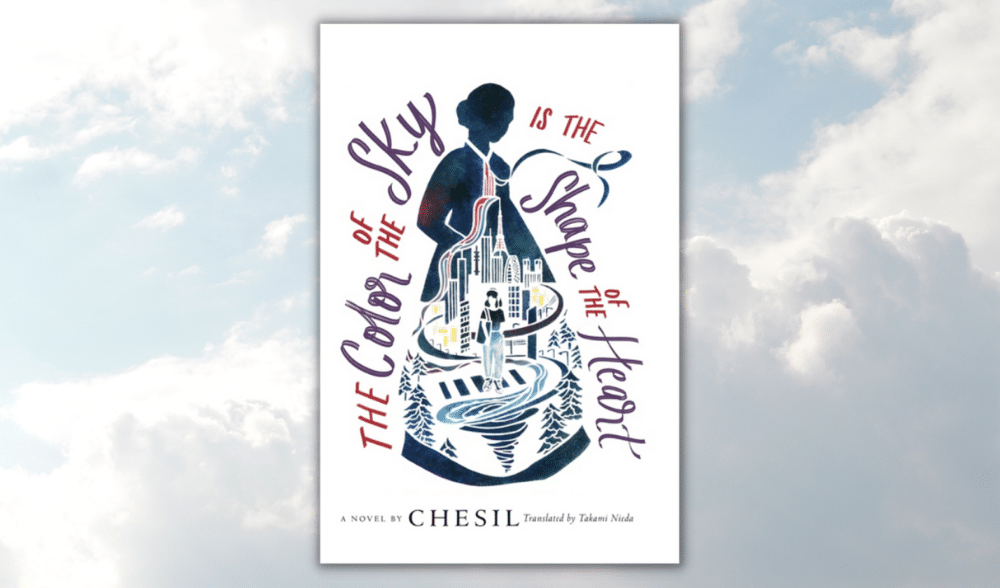

Other students, stunned, watched her commit this minor yet groundbreaking crime. The message resonated deeper than any missile test could: we can continue living even when our worldview is obliterated. We need not place our unabashed faith in one family, one belief system, or one government. It becomes clear that author Chesil’s message in her novel is that individuals should insert greater belief in themselves and their own abilities rather than in outside forces. The beauty of Chesil’s storytelling and Takami Nieda’s stellar translation is its revelation of inner acceptance and belief.

Years after the incident in her Korean school, Ginny realizes she has an answer to the seemingly impossible question asked at the beginning of the story. If the sky falls, “[she] would catch its fall.” It is not the job of the gods or dictators to distinguish right from wrong for you – it is your job to decide for yourself how to live. We are each a star that “will surely shine,” if not now, then someday.

Former LMU English Honors Graduate Ella Kelleher is the book review editor-in-chief and a contributing staff writer for Asia Media International. Her English studies featured a concentration in multi-ethnic literature. She is currently in Korea teaching English.

One Reply to “BOOK REVIEW: THE COLOR OF THE SKY IS THE SHAPE OF THE HEART (2022) BY CHESIL – A BEAUTIFUL AND HEARTBREAKING COMING-OF-AGE STORY”