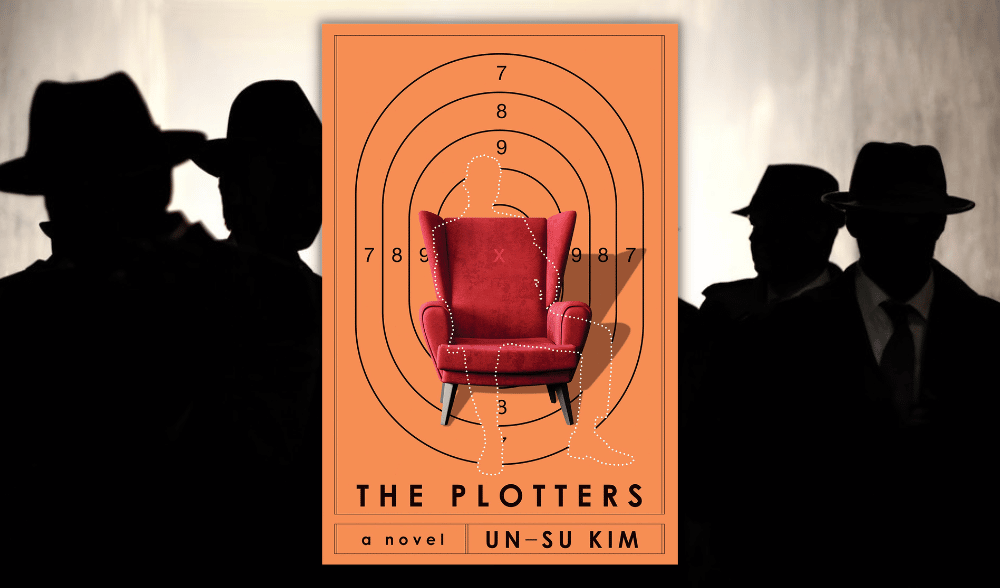

BOOK REVIEW EDITOR-IN-CHIEF ELLA KELLEHER WRITES – Government corruption. Political scandals. Contract killers. Disappearances. Set in contemporary Seoul, South Korea, the world within Kim Un-Su’s novel, The Plotters (2018), focuses on the deaths of random political figures as well as who is pulling the trigger. The shadowy figures responsible for the murders are known as “plotters” – faceless hired guns that shoot who they are told to shoot. Suspended on strings and manipulated by society’s wealthiest elites, these assassins are not meant to question their orders. Not until one of them decides to, that is.

That one was the novel’s pistol-protagonist Reseng, found in a garbage can, discarded like waste in front of a nunnery. He is discovered by a mysterious and shady father-like figure named Old Raccoon. Raised in a library that no one visits, hidden away in an unassuming alley way of Seoul, Reseng soon realizes that the “library” is not an innocent place to lose oneself in literature. The library is a front used for the main assassin syndicate of Korea’s capital. Reseng does not judge Old Raccoon, he simply does as any son would and follows into his adopted father’s path.

Fascination with stories about killers-for-hire is nothing new. Reseng somehow justifies his career choice and its glamor in a witty rant, explaining that “the oldest skull in existence has a hole in it from a spear … from the very beginning human beings have been plotting to kill each other in order to live.” Alongside prostitution, it seems that assassination is the oldest ‘profession’ in existence. Sin, in its base interpretation, seems to be embedded into our DNA.

South Korean author, Kim Un-Su made his literary debut with short stories such as “Easy Writing Lessons” (2002). He reached widespread domestic acclaim with his novel, Hot Blood (2016). He graduated to international recognition with The Plotters (2018). Brought to life by Korean American translator Sora Kim-Russell, English-inclined readers are able to access the dark witticisms and nuanced philosophical meanderings of a seedy underworld figure like Reseng. Against our apparently fragile morality, we readers even begin to find ourselves empathizing with a murderer.

Thirty-two-year-old Reseng is not your typical assassin. In-between scouting out his next victim and sourcing information about how best to dispose of them, he reads books that are otherwise never opened. Old Raccoon never taught him how to read, yet Reseng learned all by staring at the endless pages of novels on the shelves around him. Old Raccoon was less-than-cheerful at this discovery, stating that “reading books will doom you to a life of fear and shame.” Perhaps Old Racoon feared that if Reseng read enough profound literature, his ever-evolving moral compass would cause him to be led astray from his profession. However, instead of being corrupted by morality, Reseng remains apathetic. “I don’t read for any particular reason,” he assures, “… I just don’t know what else to do with my free time.”

But books cannot drown out the grim reality of his daily life. Alcohol does just the trick. Reseng justifies this coping mechanism as being “perfectly natural.” He views his assassin life as “fate” and accepts that he will likely die by being “disposed of” one day by a fellow plotter. Reseng, unlike most of us would, does not resist this inevitability. He instead embraces it without any fear of death, as anything less than that would be beneath him. Soon enough, Seoul’s arena of contract killers start to target one another in an internal war that paints a big red target on Reseng’s back.

During his struggle to out plot the other plotters and avenge the death of his close friend, Reseng meets one peculiar character after another. In addition to his villainous father-figure, there is the Barber, an elderly man who doesn’t only cut hair in his quaint little salon. There are also three very strange women: a Robinhood figure whose sole mission is to destroy the assassin syndicate and eat the best “liver and blood sausage” in Korea. Alongside her is her wheelchair-bound sister who, while being a full-grown woman, acts more like a happy-go-lucky little girl who cannot seem to stop giggling no matter the situation. In the periphery is Old Raccoon’s librarian who turns out to be a spy, as no one would suspect a woman, especially one that is cross-eyed and seemingly ill-equipped to spy-straight.

As it turns out, the concoction of these three women turns out to be deadly as they all want nothing more than to watch the library and all it stands for erupt into flames. Naturally, Reseng is just the right type of “idiot [to] pull it off.” Reseng is resolute in finding out the reality behind the assassin syndicate, so his depressed apathy turns into stoic determination. His mission may cost him a fortune, his only chance at a normal, happy existence, and his life altogether. Will our unlikely antihero rise out of the underground like a noble, new-age warrior in a triumphant climax?

A popular contemporary read among South Koreans, Kim Un-Su’s novel is deserving of Western audience’s attention. Alongside the K-drama trend of damning the rich and wealthy for their shameless opulence and thinly veiled decadence, Korea’s literary scene is making its way toward powerful sociopolitical critiques that may change way the youth views their future. The Plotters is a story full of surprises, quintessential comedic timing, and colorful characters to root for. Possibly the biggest shock of all, however, is how we readers end up genuinely empathizing with a murderer and siding with him against the elites who rule South Korea.

LMU English major graduate Ella Kelleher is the book review editor-in-chief and a contributing staff writer for Asia Media International. She majored in English with a concentration in multi-ethnic literature.