WRITES TOM PLATE – In the pantheon of American movies, the 1985 flick ‘Back to the Future’ does not rank at the top of temple Hollywood, as do canonical masterpieces such as ‘Casablanca’, ‘Gone With the Wind,’ ‘Lawrence of Arabia” and others. Yet the movie title alone enriched American argot, as in ‘been there … done that,’ and today works perfectly to capture the latest turn in U.S. foreign policy. Yes, it looks like it may be ‘back to the future’ again, as in … war preparation.

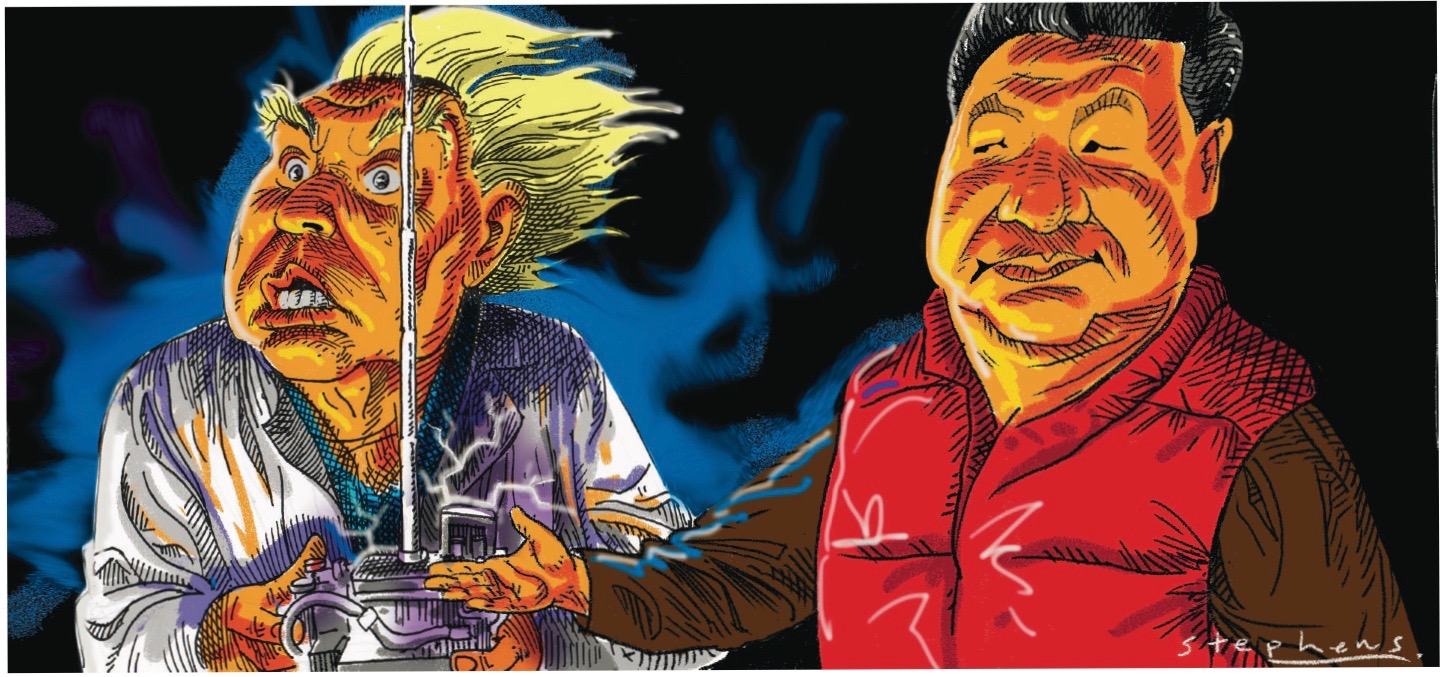

The Trump Administration has revealed defense priorities that have the chilling feel of a cold-war emphasis – rather than a no-war aspiration. The world has just been told that the 2019 Pentagon budget – topped up at US$716 billion – comes packaged as an “aggressive defense strategy.” Defense Secretary (and retired United States Marine Corps General) James Norman ‘Mad Dog’ Mattis, viewed as one of this bizarre administration’s more balanced brains, cites threats from China and Russia. Both political Left and Right, argue some U.S. think-tank types, seem in increasing concurrence on two nostrums. One is that the Indo-Pacific region is the globe’s number-one geopolitical theater (agree). The second is that America must do much more to counter an “increasingly authoritarian, mercantilist and aggressive” China.

Sane or provocative? Who knows what the U.S. now wants, but what is worrisome is the ever-hovering Law of Unintended Consequences: One builds up for peace but winds up with war.

The current depressing drift in the U.S. reflects conceptual minimalism – an ideology of win-lose, a retreat to the default of us-vs.-them, and a rejection of visionary global leadership for petty policy provincialism. “America First does not mean America alone,” Trump insisted in Davos. “When the United States grows, so does the world.” But how can that be the case if it grows small-minded?

Small minds tend not to beget big ideas. One of America’s great diplomats was the late George Kennan. The U.S. Foreign Service author of the ‘Long Telegram’ from Moscow coined – and mostly even defined – the iconic policy of “containment” as the needed antidote to the poison of the former Soviet Union. And though Ambassador Kennan’s excoriation of Soviet communism never waned one bit at Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School, where he retired to become an unforgettable teacher, the true genius of the containment notion was its aim: not to provoke uncertainty but to offer a bedrock of predictability. But when the USSR collapsed from internal decay, the simplicity of this organizing idea went poof as well. One day, out of frustration, a few Washington influentials trekked to Princeton hoping the master might give birth to a new trope, as it were, to re-frame U.S. policy. But, according to dinner participants (alas, I was not present), Kennan resisted the challenge with the sigh that world was exploding in too many directions for conceptual miniaturization. At the same time Kennan, who died in 1995 at the age of 101, had little appetite to advise anyone to go ‘back to the future’.

The global provincialism of President Donald J. Trump is a symptom of the current default to the past, including tariff tantrums and potential trade wars that will harm U.S. consumers as well as foreign producers; but he is not the core cause. The new provincialism goes deep: After all, Trump’s considerably more thoughtful predecessor preferred “leading from behind.” But whether from the back or the front, Asian nations from the Philippines to Vietnam – and perhaps also Singapore and Malaysia – need the United States to act with intelligence and foresight. What is needed is a committed effort to formulate a cosmopolitan internationalism, fiendishly multi-sided; but rarely is anything truly important easy to achieve.

The problem with the win-lose paradigm is that someone always loses; the argument for win-win is, why risk being a loser? It should not be hard to decide which of these two approaches offers the best odds for geopolitical and economic stability. This outlook would prove less difficult to realize were it matched by an expansive dose of cosmopolitanism from China. Americans worry – and increasingly so – that Beijing is striking a more global posture than Washington but the new “nice’ hegemon profile is but a pose. One Harvard professor even titled his latest book (superb, other than the awful title): ‘Destined for War’.

China will stumble if it needlessly brews its own cold-war rumble. Big powers advance best with little steps. This sensitive point was conveyed deftly at last week’s World Economic Forum summit in Davos, Switzerland. A tactful Singapore Minister Chan Chun Sing came across as more than happy to accept China’s imaginative and ambitious New Silk Road program as a credible potential trigger for our world economy’s “next phase of growth.” But – seemed the minister’s subtext – Beijing needs to stop scaring people in the Asian neighborhood half out of their wits if it proposes to begin “leading from the front” with elan. Said Chan: “I can understand and I have heard theories where people are afraid, hesitant about China’s growth. But this is an important historical opportunity for China to convince the rest of the world that actually its actions have a broader perspective…. The Chinese have a saying: yi de fu ren – use your benevolence to bring about a global community.”

This felicitous phrase was the one trumpeted by President Xi Jinping in his Davos speech last year. The optics of the current Chinese government plumping for an expansive internationalism contrasted brilliantly – and cleverly – with the self-centered darkness of the then-newly inaugurated American president. And it still does. Back to the future – if America is prepared to go small conceptually, while blowing up militarily? Or boldly into the future goes China – yi de fu ren? That’s the daunting, haunting mystery of our era.

Loyola Marymount University Professor Tom Plate’s books on China include the recent ‘Yo-Yo Diplomacy’ and ‘In the Middle of China’s Future’ (with an introduction by Kishore Mahbubani.