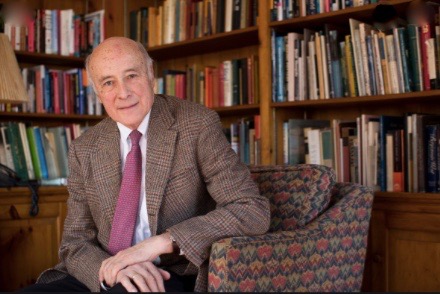

HYUNG JUN YOU WRITES — When Joseph Nye, a renowned Harvard scholar in international relations, told his colleagues that he was going to write a book on how mortality plays a role in foreign policy, they said it was going to be a short book. This is international relations, where national interests run supreme and countries compete in an anarchic world. The strong do what they will and the weak suffer.

Professor Nye wasn’t satisfied with that answer.

“If you have that view, that cynical view, you’re going to get history wrong,” he said, and pointed out that past foreign policy records proves a president’s ethical view matters.

Nye’s focus on how power, both visible and invisible, can be wielded in foreign policy is controversial in conventional circles. Politicians remain insistent that the world is an anarchy and therefore foreign policy must remain amoral.

In truth, American foreign policy has been a balancing act between protecting national interests and promoting values. Since World War II the power of the executive branch grew immensely, thus putting the president at the center of formulating U.S. foreign policy. So, from Truman to Trump, how has a president’s personal moral reasoning shaped foreign policy? And how can we come up with objective standards to judge a president’s action?

With his new book, Do Morals Matter?, Professor Nye attempts to answer those questions. It could not have come in a more tumultuous time in the American presidency, where the current occupant of the White House is upending U.S foreign policy norms and methods.

Professor Nye granted Asia Media International an interview to discuss his new book, Trump’s presidency, and beyond.

The following interview has been edited for clarity and length.

What gave you the inspiration to write this book? Was it related to the action from the current administration?

I had actually been thinking about this for a number of years, and a couple of decades ago I had written a book called Nuclear Ethics — about the ethics of nuclear weapons. But I confess that the current administration made me feel that this book was more relevant than ever and that it was important to get it written.

Were your colleagues receptive of your book?

So far I’ve had a very good reaction from colleagues, but it’s also true that professionally many people in international relations downplay the role of ethics and morals. As I say in the book, they tend to think everything is determined by national interests and that politicians sprinkle a little moral icing on it to make it look pretty. And what I tried to show in the book is that if you have that view, that cynical view, you’re going to get history wrong. And I show in a number of these cases of since 1945 that Presidents’ ethical views did make a big difference.

The public often focuses on having good intentions. And so they all say, if a president talks about democracy and freedom, they call that moral clarity. But it’s not enough to have good intentions. You may have moral clarity in your statements, but if you have bad consequences, which are highly immoral, that doesn’t make a moral action. The moral clarity has to be balanced by equal attention to appropriate means and good consequences.

What you’re basically trying to say is that the public tends to focus more on the rhetoric than the consequences.

Yes

In your book, you gave Trump a good scoring on use of military force but on the rest you gave him a poor scoring.

That’s right. The one thing … has been restraint on the use of force. His use of force has been limited to combatants and has been proportional. So I give him credit for that. But if you look at his rhetoric, it’s much too narrow in defining the way America sees its interests, failing to include the interests of others. And if you look at the other means that he uses, including respect for the rights of others, he doesn’t score well on that. And if you look at the consequences by weakening American alliances and by weakening the multilateral institutions that provide a structure and stability in international politics, he doesn’t score well on that either.

It seems like you are trying to argue that American foreign policy is a battle between Kissinger’s realism and Samantha Powers idealism, to put it one way. Do you think that’s a correct way to put it, a balance between those two ideals?

Well, there is a tension between realism and cosmopolitanism, but I do argue in the book that they can be reconciled. That we want a mixture of both in our policies. What I say in the book is you should always start with realism, because if you’re not realistic about the world, you’re going to make a mess with immoral consequences. But what I fault some of the realists for is they start and stop at the same place. There are many instances where international politics is not a matter of survival.

Foreign policy requires a balancing of security, economics and values. If you only pursue values you would have the human rights policy and no foreign policy. On the other hand, to have a foreign policy that only focuses on security, it is to sell short the importance of morality.

Do you think President Trump is keeping the same trajectory of President Obama and Clinton’s policy? Because some academics argue that.

No, I think he’s made more of a change in our policy. Every president after 1945 until 2016 accepted the international order, which the founders, Roosevelt, Truman and Eisenhower had established. And which was based on US alliances and multilateral institutions. Trump is the first candidate of a major party in 70 years to basically downgrade those alliances and intuitions.

Do you think that Trump has changed the game forever or can the United States take back the leadership role and the moral high ground?

I think some of that will depend on whether it’s four years or eight years. I think if he is reelected and we have eight years of damage to alliances and institutions, it’s going to be harder to repair. As a friend of mine from Japan, once put it, “You can hold your breath for four years. It’s harder to hold your breath for eight years.”

You’re basically saying that President Trump’s damage to the institution is going to be long lasting?

Yes. But again, depending on what happens in November. It may not be permanent.

Right.

In other words, it may be something from which we can recover.

Recent LMU graduate Hyung Jun You, an International Relations major, is heading for graduate school in international studies.