CHARLES E MORRISON WRITES — About two turbulent months ago, former Vice President Joe Biden had established a commanding lead in the Democratic nomination campaign, although his two more liberal competitors had not yet ended their efforts; and the looming coronavirus pandemic was threatening to fundamentally transform the political landscape. And it did. In the weeks that followed, it resulted in most of the country under stay-at-home orders, the suspension of many primary elections, the closure of Congress and state legislatures, and an odd, temporary lull in politics as usual.

These social distancing strictures are now being gradually relaxed, and the U.S. Senate, but not the House, has resumed in-person meetings. But deep uncertainty remains about the future course of the pandemic, and it will certainly be a major factor in the 2020 elections.

The 2020 Pandemic

The pandemic hit the United States in full force in early to mid-March, but research suggests that the virus had been invisibly circulating much more widely than realized before that time. There had been great concern in specialized medical circles when the virus first appeared in China, but the nation as a whole was slow to react and prepare. The first confirmed case of COVID-19 in the United States was in Seattle on January 20, a returning visitor to Wuhan. On January 31, when U.S. restrictions on foreigner travelers and direct flights from China were announced, there were still just a handful of known cases in the United States. By the end of February, confirmed cases had slowly increased to 62, by March 15, they had risen to 1,700, by April 1 to 163,000, and by the beginning of May to more than a million.

U.S. efforts to prevent the spread of the virus, inhibited by partisan politics, occurred too little, too late. Just as it was not contained at first in China, it was also not contained in the U.S., especially in comparison to Asian societies close to mainland China such as Taiwan, Hong Kong as South Korea. Travel to and from the European Union were not restricted until March 13, by which time the disease that been introduced in New York by dozens of such travelers. It spread out in most of the United States from there. Probably the biggest technical lapse was in the unavailability of test kits, which failure hid the spread of disease. The Center for Disease Control (CDC) had sought to build its own and at first failed, delaying accurate testing for weeks. Even today, testing remains mostly only of symptomatic persons who have appeared at a hospital or doctor’s office, and thus the number of those exposed to the novel coronavirus, even if not suffering from the COVID-19 disease associated with it, may be orders of magnitude higher.

Without an antidote, the key way to address the contagion was through various forms of “social distancing,” designed to slow and reverse the spread, but not a cure, as well as through tracing contacts for confirmed cases of the disease. An important measure of success is the “reproductive” rate or “RO,” the average number of other persons one infected person infects. If RO is above 1.0, the disease is still spreading.

Social distancing is a natural self-protective human action that occurred throughout the country, even where not mandated. In general, however, the states that mandated prompt and wider ranging social distancing measures earlier appear to have been less impacted by the disease. Washington State and California are examples of comparative success stories. States, like New York, where initial infections were more numerous and restrictions were applied later suffered proportionately greater. Virtually all states closed educational institutions and team sports and limited the size of gatherings, and all except five states adopted “stay at home” orders for “non-essential” workers.

The Reopening Debate

While there is a lot of uncertainty about all figures, the reproductive rate has apparently fallen below 1.0 in many states, but unlike Italy, Spain, Germany or many other smaller EU countries, there has been no sharply downward slope in the U.S. of either confirmed new infections or deaths. Instead the country seems on a plateau, but with each passing week, there has been increasing clamor to restart the economy, cheered on by the President. Just as the country closed down in patchwork fashion (reflecting diversity, the lack of strong central guidance and the federal system), a patchwork pattern of re-opening threatens to have suboptimal economic as well as disease fighting consequences. These, of course, are connected since opening is not just a top-down matter of allowing prohibited activities to resume. It is also bottom-up; people have to feel the pandemic is sufficiently controlled to safely engage in these activities. At this point, it appears that it will be months, if not years, for the economy to recover, and recovery does not mean just returning to the previous “normal.”

While most Republican and Democratic governors are cautious in balancing clearly related health and economic needs, by early May the general mood across the country favored removing restrictions, increasing pressure on local officials, even those who would prefer to err, if at all, on the side of caution. The mood is driven by high unemployment, depleted state and local treasuries, and, of course, boredom and a desire for “normalcy,” and it is buttressed by increasing evidence that the mortality rate of the virus is relatively low, (perhaps particularly for young people), and especially when an unknown population of asymptomatic untested cases are brought into the ratio. President Trump’s political and business interests lie in this direction, and he has not hesitated to place himself in the forefront of the bandwagon of those pushing for “restarting” the economy, even where his own government’s guidelines for reopening have not been met.

An Altered Political Landscape for President Trump

The coronavirus dramatically is altering the salient election issues and perhaps how the election may be conducted. Reelections for a second term are usually a referendum on the incumbent, and that is certainly the case this time. It may be best thought of as a pro-Trump vs anti-Trump election rather than a Trump vs Biden one. Prior to coronavirus, the President, despite weaknesses in his national approval rating and failure to expand his base beyond his party, had one overriding advantage, a strong economy. Unemployment, which had dropped steady under the previous administration had continued its downward trend to effectively full employment, while the stock market also continued an upward trajectory despite underlying late-cycle weaknesses of a years-long boom. In late January, the strong economy was the theme of Trump’s boastful speech at the World Economic Forum. Trump and Republicans were counting on the association of the strong economy with Trump to carry them to victory despite the devastating losses in the mid-term Congressional elections in 2018.

In a very short order, the COVID-19 crisis erased much of the stock market gain in the Trump years, hammered the GDP, and caused the unemployment rate to soar from 4.4% in March to 14.7% in April, heights unseen in three generations. This knocked out the major props underlying the Republican campaign. At the same time, the crisis focused attention on Trump’s management skills, and diverted attention from his competitor. This has accentuated the stakes for Trump, but it has also created challenges for Biden.

Trump is known as a transactional president who revels in deal-making, often by taking extreme positions for bargaining purposes, thus exposing himself to political risks, for example, of losing agricultural markets. He says he follows gut instincts. He loves rallies of his most devoted and partisan supporters and continued in campaign mode as president. He is not been known for providing long-term strategic direction, studying and pondering issues carefully, portraying facts accurately, engaging in multilateral global leadership, or providing steady, inspiring leadership for the nation as a whole. Thus, the pandemic accentuates his weaknesses as a president rather than strengths. While his most devoted fans, who identify with the President, have excused every twist and turn, his standing with the small but pivotal group of truly independent voters has plunged.

It is both in Trump’s political and business interests and his character to want to reopen the economy as quickly as possible. At one point in March, against all medical advice, he urged that the churches be full for Easter, only to quickly drop the idea again. He has talked up the potentialities of treatments and vaccines that are speculative and at best only on the horizon.

But his now suspended daily press conferences, begun in part as a substitute for the partisan rallies, brought his weaknesses most into view. Despite some efforts to do so, the President was unable to switch his modus operandi for the crisis situation, insisting that he, not his doctors, be the star, introducing petty partisanship unbefitting a crisis, evading responsibilities, and engaging in verbal insults with some journalists. He also failed to sound empathetic with victims of the disease. His worst moment came when he naively asked whether there were ways disinfectants could be used internally, indicating that he was asking as a smart person.

Buoyed by party and fan support, Trump’s overall approval job rating has remained close to 45 percent. It was only slightly higher, in the low 50s nearer the beginning of the crisis, far lower than what one might expect during a crisis. Trump’s campaign staff are particularly concerned about weakening numbers in swing (or ‘purple’) states and in key Senate races, threatening a Republican loss of the Senate. There is evidence of decline in support of long-standing Trump bases – more religious Americans, less educated voters, and senior white males. The President’s forward leaning position on reopening the economy, while in synch with desired direction, often sounds too risky to many voters who prefer a safe opening and mistrust the partisan president.

In contrast to the impeachment period, other Republicans have begun to distance themselves from Trump. Some Republican governors have ignored or even criticized him on COVID, Senate Republicans have rejected his idea of reducing payroll taxes, and many candidates at state and local level are deemphasizing their support of Trump in campaign material. Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell even joined House Democratic leader Nancy Pelosi in a joint letter rejecting the President’s offer to have Members of Congress tested.

We will turn to the Democrats, but a word first about how other chief executives in the American federal system fared – the governors – because, in contrast to Trump, many of them politically benefited by showing effective and mostly nonpartisan leadership.

Governors to the Forefront

In the absence of strong national leadership and given the nature of the American federal system, governors were suddenly in the spotlight, taking the lead in shaping the emergency response in their states, seeking medical supplies (which the President urged governors to find), providing information on the disease, and, more recently, detailing opening up plans and actions. Although there were many actions also at the city and county level, governors were the most visible and impactful level of government to ordinary citizens.

In general, they provided a contrast to the President. They were largely science and fact-based, and emphasizing actions on behalf of their citizens as a whole. Since this was what the public craved, the performance of state governors and local officials rose, whether Democratic or Republican. The daily press conferences of Andrew Cuomo, the governor of the hardest hit state, New York, catapulted him into the national limelight as a kind of anti-Trump, causing some Democrats to wish he were their nominee rather than the elderly Biden. In New York, Cuomo’s approval for handling of COVID soared to over 70 percent, approximately double the percentage of New Yorkers approving Trump’s handling. A poll in the third week of April showed the most popular governors for handling COVID were Republican governor of Ohio Mike DeWine with 83% approval, Democratic Governor Andrew Beshear of Kentucky with 81%, and Republican governors Charlie Baker of Massachusetts and Larry Hogan of Maryland tied at 80%. In every single state, the governor’s approval rating was higher than the President’s. These ratings, as well as the increased popularity of foreign leaders who responded effectively such as Angela Merkel in Germany, Moon Jae-in in South Korea, and Jacinda Ardern in New Zealand illustrate the opportunities for leaders during crises. Trump not only fumbled the opportunity, but is now fighting to retain his support.

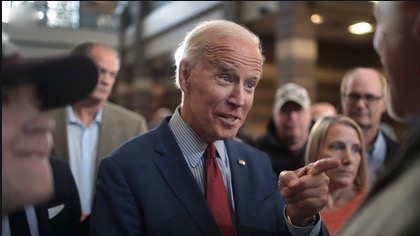

Biden on the Backburner

In the meantime, Joe Biden, without an executive or legislative platform, has struggled to get visibility for his campaign. Like Warren Harding exactly 100 years ago, who famously campaigned for president from his porch, Biden so far has been confined to his house, albeit with a high-tech television studio. He is in a somewhat difficult position since he does not want to appear to be making the president’s job more difficult during a crisis when people seek national leadership, but at the same time not to ignore the Administration’s disorganization. The crisis has benefited Biden in some ways, and not just because Trump has been unable to exploit it. Since he had already amassed the delegates and endorsements to almost certainly win the nomination, it provided a reason for the remaining candidates, most notably Bernie Sanders, to close their campaigns and provide the inevitable endorsements. Sanders regards himself as the leader of a “movement,” and he will continue to seek support for his movement and ideas. At the same time, his endorsement came far earlier than in 2016, and the two men enjoy a long and positive relationship. With Elizabeth Warren also endorsing, the way was clear for former President Barack Obama to endorse as did Hillary Clinton, providing the image if not the substance of a unified Democratic party. This made Biden the “presumptive” nominee, but he does not formally become the candidate until a Democratic convention can be held.

Biden also spent his time to plan for a running mate, and he announced that it would be a woman and established a vetting committee. Given his age (78 by Inauguration Day), this is an especially important choice. He also was meeting virtually with funders, his staff and advisers as well as medical and economic experts, and he unveiled a ‘re-opening’ plan, which has received almost no attention. While some supporters are disappointed in his relative invisibility and believe he needs to strike out more aggressively against Trump, others defend his using his time for preparation and developing a solid national campaign strategy.

The former Vice President has not previously proved to be a very effective national level vote-getting or a great debater. His weaknesses include verbosity, misstatements, and a tendency toward being thin-skinned. The Trump campaign has tried to portray him as lacking energy (“Sleepy Joe Biden”) or in mental decline. But Biden also projects an image of experience, steadiness, and balance, and his association with Obama stands him in good stead with the important black minority community. He does not elicit the strong negatives that Hillary Clinton did with many voters. Most reassuring to Democrats, he appears to have strengthened his position with younger voters and, perhaps because of COVID, senior citizens. Biden is hoping that after more than three years of mercurial leadership by Trump, he will be seen as a safe, steady hand. He also has an enormous pool of talented people to draw upon.

One unexpected turn has been that a former short-term staff member in his Senate office who had claimed that Biden had sexually harassed her 27 years ago recently escalated her charges to say he tried to rape her. This is unexpected because this is Biden’s third national campaign and such charges have never come up before. Biden has denied the allegations, and has asked for any official records relating to her allegations to be made public. Because the charges are old and do not appear consistent with Biden’s reputation, they may have limited impact, but they underscore the need for the Biden campaign to move forward with a positive agenda so that he is not seen to be in the news just to defend himself.

The Forthcoming Campaign

Current polling suggests that Biden enjoys a lead over Trump nationally. But most possible Democratic nominees enjoyed polling leads over Trump for months, and since the country votes, with minor exceptions, in state-level blocks, the key to the election are the so-called battleground states. In 2016, in three of these – Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin – a tiny margin of 0.06% of American voters shifted 8.5% of the Electoral College votes into Trump’s hands, giving him the victory. Biden was born and grew up in Pennsylvania, where he enjoys a lead, and he is also leading in the other two states, narrowly in Wisconsin. Other populous battleground states include Florida, Ohio, and North Carolina.

Six months is a long-time in American politics, especially remembering that in May 2016 Trump was given hardly any chance of winning that election. This time, Trump is gambling by pushing opening up the economy, and this positioning may help him if the disease recedes. But if there is a second wave, the image that he was playing with people’s lives for political advantage will surely haunt him. There could be also be a scandal or an egregious debate performance. And, given the age of the two candidates and the pandemic, there is also a slight chance that one of them could be incapacitated or pass away before the election. Much more likely is that it will be a very dirty, very close, and very expensive election. Trump’s long-developing campaign appears to have a clear early edge in funds and digital strategies.

Election Issues

COVID and Health. These are very important issues for the Democrats. Inadequate health care and Trump’s assault on popular aspects of the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare) were already hot-button issues for them before COVID-19. Now they will seek to paint Trump as inept in responding to COVID. But health can also a tricky issue for Democrats as the liberal wing of the party is in favor of a much more robust state medical insurance system than Biden or other moderate Democrats support. Trump will seek to paint Biden as a liberal or even socialist. Unlike impeachment, largely seen as an inside-the-Beltway Washington debate, COVID has had a real impact on Americans, and so it will not disappear in the election. It is hard for Trump to deflect his handling of COVID to blame Democrats and Biden or China. Expect health and social safety net issues more generally to be plus factors for Biden.

The Economy. The Republicans have indicated that they believe that Trump’s earlier performance on the economy can be leveraged to argue that he is in the best position to restore growth following the epidemic. Democrats will support some of the measures Trump took, but argue that he went too far on deregulation, that his tax cuts mainly helped the rich, and that his trade policy may have addressed the right issues but in the wrong way.

China. The Trump campaign has also indicated that they intend to make a big issue of China policy, saying that Trump has been tough with China, while Biden has been too friendly with Chinese leaders. The public, already sour on China, has become increasingly so with COVID. Both sides have put out advertisements that attempt to paint themselves as strong and the other as weak on China. Fact checkers have been critical of these advertisements as misleading on both sides. While Trump has a clear advantage in being able to say that he took retaliatory action against China on trade issues, he is on the defensive with respect to disease because of his expressed confidence that Xi Jinping, with whom he claims a positive relationship, was handling it well. This deserves a longer discussion later, but it is probably not so much the virus, but the depth of the recession that will determine how deep and potent the anger with China becomes. With both candidates having vulnerabilities, it is difficult to see an advantage for either side. Other domestic issues are more likely to come to the forefront as the election becomes closer, but Trump’s efforts to assign blame to China and the World Health Organization for COVID can be expected to continue.

Immigration. This will continue to be a strong card for the Republicans and a difficult one for the Democrats since recent immigrant groups, especially Hispanics and Asian-Americans, tend to be strongly Democratic. In contrast to 2016, Trump may want to focus away from the southern border and incomplete wall while still trumpeting a strong effort to restrict immigration. Democrats will criticize cruel aspects of the policy and the poorly thought-out strategy behind it, but, like China, they will avoid criticizing the direction, particularly in a time of high unemployment.

Leadership and Integrity. This may become the main issue for Democrats because of Trump’s impulsive style, staff turnover, nepotism, lack of attentiveness to issues, and demonstrable record of exaggeration and prevarication. The Trump campaign has sought to mitigate his own weaknesses by exploiting Biden’s vulnerabilities, including his son’s trading on his name in China and the Ukraine and the Tara Reade accusations. But less importance than scandals will be the overall confidence in the individuals. Again, this will be less about Biden, more about Trump.

Getting Out the Vote.

In the end, barring some major new development, the number of truly undecided and persuadable voters is probably in the 5-10% range at a maximum, far lower than the 30% of voters who say they are independents because they are not party members. A large share of these lean one way or another and end up voting as they lean. Because the range is relatively small, getting out their voters in the battleground states will be all the more important for both candidates. This, of course, may be complicated by a second wave of the virus. Biden’s weakness is that he is not a deeply inspiring or motivating candidate, but his strength is that he does not elicit the highly negative feelings that both Trump and Hillary Clinton did in the previous election. This means that normally Democratic voters are less likely to vote for his opponent or third-party candidates. But ironically, in a Trump vs. anti-Trump election, Trump is more likely to get out the Biden vote than Biden himself.

Dr. Morrison, the former long-serving head of the renowned East West Center in Honolulu, is an independent political analyst and member of the board of the Pacific Century Institute, a partner of LMU’s Asia Media International. He is the author of many articles and books of considerable note.