(This is the fifth in an original series about new wave feminist writers in Korea whose work has started to reach English language readers via superb translations.)

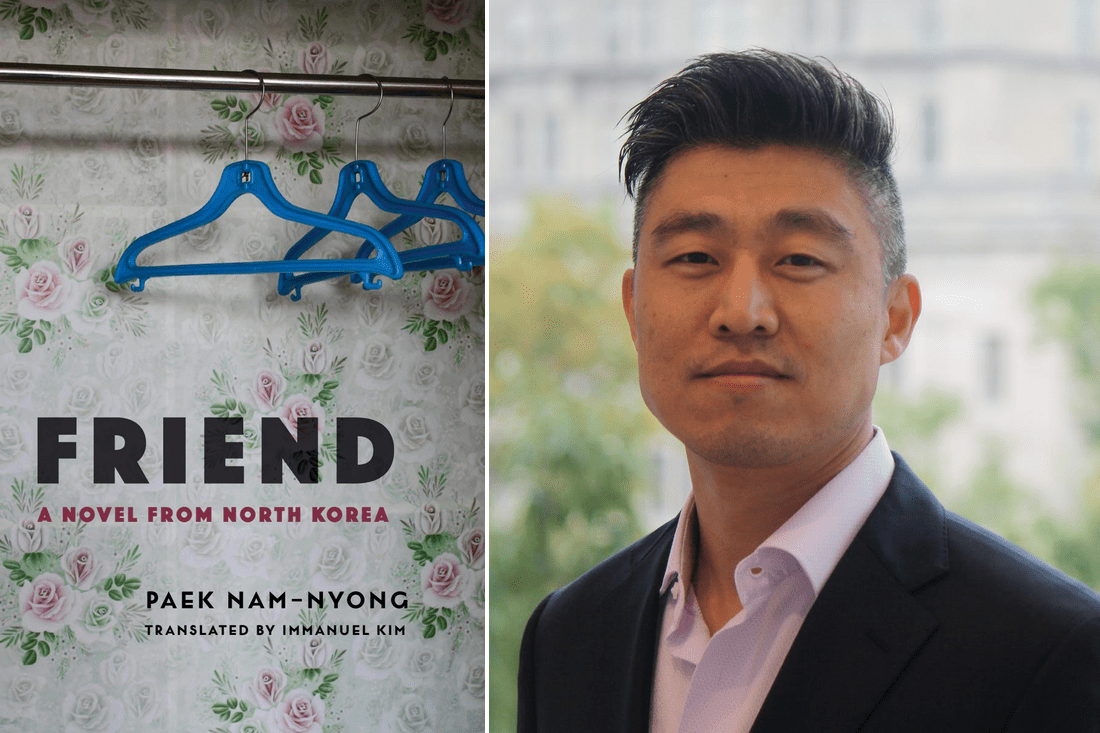

ANDREA PLATE WRITES — Thirty-eight years. That’s how long it took for the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea to approve, for publication in the United States, its 1988 blockbuster novel Friend (Columbia University Press). The North Korean bestseller was adapted for television at home, published four years later in South Korea and 19 years later in France.

Never mind the decades of delay. The American publication of Friend is a monumental achievement and the novel, quite literally, is beyond compare. English language literature is rife with tales told by North Korean defectors, most stunningly, perhaps, Seoul-based Hyeonseo Lee’s 2015 The Girl with Seven Names: Escape from North Korea. Our only other exposure to “inside” North Korean literature is the short stories of the pseudonymous “Bandi” (Korean for “firefly”), which were smuggled out — from North to South Korea in 2014, then translated a few years later into English.

Friend stands apart. It is a first, in many ways: The famous North Korean author still lives in his home country, and is still in good-standing with the current regime; translator Immanuel Kim, a highly-regarded, American-born professor at George Washington University, has traveled to North Korea to interview the author; and the subject matter covers high-order, hot-button topics such as divorce, women’s rights and the fluidity of gender roles in modern North Korea.

The novel presents three central characters in pursuit of a common goal: to settle the divorce petition of an unhappily married couple. Lee Seok Chun is a dutiful, dedicated lathe worker but a deadbeat husband, more passionate about his factory tools than his wife; Sun Hee is an iconic opera singer, more passionate about music and her rising social stature than her husband; and Judge Jeong Jin Wu, more passionate about preserving marriage as a pillar of the state than interpersonal harmony …or justice, or anything remotely resembling neutral arbitration—and for good reason. The judge is tasked to do the seemingly impossible: solve this tormented couple’s troubles while also satisfying the divorce averse People’s Committee. A secondary character is the judge’s wife, biologist Eun Ok, who once promised her husband “eternal love, a harmonious family and positive results from the research lab.” Not always in that order.

Readers, take note: Divorce, North Korean style, is not the institution as we know it. There is no such thing as no-fault divorce. All parties involved are at fault — man, woman, judge — for having failed to preserve the status quo. And so, Judge Jeong Jin Wu is haunted by memories of previously granted divorces, “knowing that he was destroying a family, a unit of society.”

To be sure, this text is somewhat didactic, even propagandistic. Factory tools are “emblems of diligence and dignity.” Seok Chung finds his lathe work “truly rewarding, and like the sound of the rapids, it, too, has a melodic tune.” The judge, shocked by the shenanigans of a corrupt apparatchik retorts, “Isn’t it your duty as a chairman to increase the expertise level of the workers rather than to increase profit?” (Would anyone dare answer “no?”) He is equally shocked by the temerity of Sun Hee: “Why does she want a divorce? Perhaps her husband is impotent. No, it can’t be that. She has a son.”

One might be tempted to snicker at seemingly slick slogans and semi-stock characters (however highly nuanced, they are not entirely unlike the comic caricatures of North Koreans in 2014’s “The Interview,” starring Seth Rogen and James Franco as TV journalists attempting to interview Kim Jong Un). But Friend is no joke. Like most DPRK writing of the post-Korean War era, it moves beyond purist, preachy socialist realism to portray the clash of yesterday’s ideologies with today’s truths.

Ultimately, Friend tells a universal tale. Even in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, even in the Hermit Kingdom, the human condition, worldwide, transcends national norms. What pulls couples apart here, there and everywhere is: Financial strain. Workaholism. Divergent career paths. And of course, child casualties; Ho Nam, the couple’s seven-year-old son, is forced to walk himself home from kindergarten in the rain, just as Henry James’ heroine of What Maisie Knew (1897), also seven years old, learns to navigate her way through an addled adult world. Finally, even in North Korea, where workers are glorified regardless of gender, feminism is on the rise. It is Sun Hee, not her husband, who petitions for divorce, rejecting her traditionally submissive familial role. Writes Paek: “She felt that her husband did not consider her his wife but rather a housekeeper and a nanny for the children.”

Does the unhappy couple “achieve” divorce? Paek won’t tell. He closes his novel instead with a sweeping salve: “There is no one without a family. A family is where the love of humanity dwells, and it is a beautiful world where hope flourishes.”

Is this why a novel about acrimony is entitled Friend — because while marriages collapse and love fades, the state will always love its people (if they don’t divorce)?

Friend may not be the most entertaining or engaging read, but it is a tour de force for the North Korean Communist Party, the elite Writer’s Union, and author Paek, working together and reaching out, finally, to the Western world. Friend is an open book about a closed society. Can Western readers peruse it with an open mind?

Andrea Plate, Asia Media International’s senior advisor for writing and editing, holds various degrees in English Literature, Communications-Journalism and Social Welfare/Public Policy from UC Berkeley, USC and UCLA. Her college teaching experience includes Fordham University and Loyola Marymount University. Her most recent book, MADNESS: In the Trenches of America’s Troubled Department of Veterans Affairs, about her years as a senior social worker at the U.S. Veterans Administration, was recently published in Asia and North America by Marshall Cavendish Asia International to critical acclaim.

One Reply to “DIVORCE, NORTH KOREAN STYLE”