ELLA KELLEHER WRITES — Grave of the Fireflies, one of those works of art that will never die, nonetheless is a film that lacks concrete resolution – there is no main lesson to be learned at the end. The audience is instead left with the understanding of the ephemerality of life, which makes this film quite groundbreaking for the year it was released, 1988, and why it remains a must-watch. Back then, great foreign films such as this one tended to slip through the bars of critical acclaim and were relegated to becoming cult classics. We must take a second look at Grave of the Fireflies because it chooses to distance itself from the gun-slinging, action-packed war movies that we are accustomed to. It carefully avoids glorifying or focusing too intently on the violence of battle. Instead, the story that is presented is a personal tragedy, one that shakes the viewer to the core and reminds us to be grateful that we are simply spectators of tragedy and not a part of it.

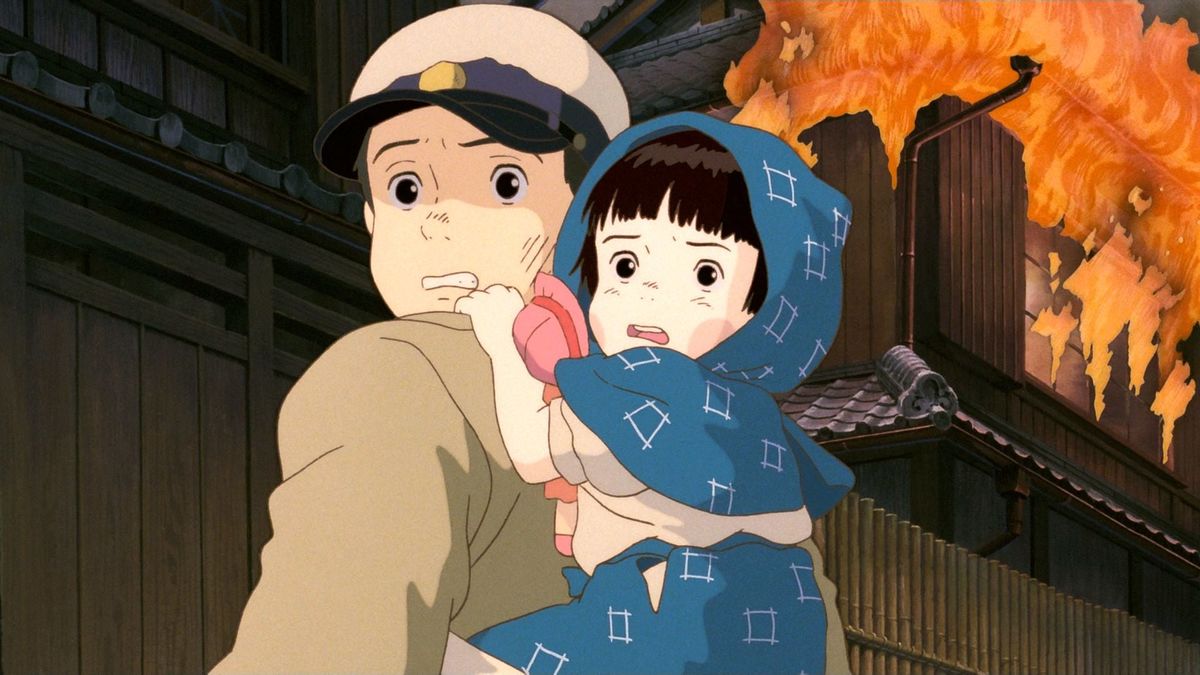

Grave of the Fireflies is based on a semi-autobiographical novel of the same name, authored by Nosaka Akiyuki. The story is simple yet devastating: two siblings, Seita and Setsuko, are utterly alone in their quest for survival in Japan during World War Two. The film begins with the death of Seita who appears skeletal from severe malnutrition. He perishes inside of a train station and his younger sister, Setsuko, is nowhere in sight. The camera slowly pans away and reveals several other young boys, all dead and lying against train station pillars. The audience is left with a circulation of haunting thoughts: who are all these other boys? Why are they all alone? Why is no one helping them?

Kindness and charity can become scarce luxuries in a country ravaged by war and mass hunger. Even the sibling’s own aunt is cruel and apathetic towards them once they move in with her after their mother dies from a U.S. firebombing raid in Kobe. The children decide to leave their aunt’s abusive household and move into a deserted bomb shelter built into a hillside. Despite the misery that this tale is entrenched in, there are moments of beauty. In one scene, the children try to catch fireflies to create a light source in their dark shelter. Lighthearted music plays in the background as Seita opens a jar filled with buzzing fireflies. The siblings lay down on the floor to watch the lightshow of insects all around them; they imagine seeing ships at sea and bustling cities at night (54:21). For just a brief moment, the children are free from the perils of war. The next day, however, reality crashes upon the two – they wake up only to find all the fireflies are dead. Setsuko carefully buries the corpses of the insects in the same manner that she imagines her mother was buried. She says, “mama’s in a grave too.” (57:06) This haunts the audience with a message that happiness is fleeting, beautiful things are tragically fragile and the only place that we might experience anything for eternity is in death itself.

The heart wrenching suffering that Seita and Setsuko face is not caused by any single villain. Instead, this film illustrates that Seita lost his sister to the shattering effects of war, and more specifically, what war and nationalism does to ordinary people. Everyone, from their abusive aunt, to the doctor who does little more than diagnose the obviously starving Setsuko with malnutrition, to the farmer that beats Seita for stealing food, are all complicit in the deaths of the siblings. The actual battling of war becomes a “mere backdrop” in this story of survival. Graves of the Fireflies decides to highlight the ripple effect that war has on non-military civilians. The central message is that the effects of war itself “blinds us from all things human,” and has the ability to change regular people who were once kind and generous and turn them into selfish and unsympathetic monsters. The nationalistic fervor of the Japanese during World War Two caused them to “suffer more due to their change from communalism to selfish survivalism.”

In a particularly painful scene, Seita manages to scrounge some food for his starving younger sister. He rushes back to their shelter where he finds Setsuko being eerily quiet, weak, and covered in dirt. Seita feeds her a small bite of watermelon, but she is too fragile to properly consume it on her own. Setsuko whispers in a frail and barely perceptible voice, “it’s good. Seita, thank you.” (1:18:15) Despite the darkness of this moment, Setsuko manages to smile and show genuine love and warmth – something the adults in the film never showed her or her brother, even in their most dire moments. Despite experiencing immense pain from dealing with the agony of a slow death, Setsuko makes the decision to embrace her humanity and innocence, making her death all the more tragic.

Grave of the Fireflies establishes an interesting idea through the deaths of both Setsuko and Seita. Normally in film, the main characters will try to change the corrupt system they are trapped within or break it apart altogether and ultimately improve their quality of life in doing so. Good examples of this trope are, The Hunger Games (2012) or, V For Vendetta (2005). Instead, Grave of the Fireflies chooses to challenge this conventional plot structure. This film posits the idea that sometimes people have no choice but to stay trapped in broken systems, sometimes people are only given two choices: to either remain in an evil society or die trying to escape from it. This is ultimately what kills Seita and Setsuko, as the turning point for them was the moment they decided to leave their abusive aunt’s household, this act of escape sealed their fate of inevitable demise.

Grave of the Fireflies is not necessarily the kind of film which demands a call to action from its audience. Rather, it forces the audience to watch a tragedy from a comfortable distance, essentially problematizing the perspective of the viewer. There is a scene where several local children, about the same age as Seita and Setsuko, stumble upon the sibling’s shelter while they are not there. These local children do not steal anything or break anything during their time poking around, they simply remark on how, “nobody [they] know would ever eat stuff [like] [that],” in reference to the pitiful meals the siblings were forced to eat. These children are appalled at the horrid living conditions of Seita and Setsuko, and after seeing enough, they decide to leave. These random children represent the position of the audience watching the film-we can witness a tragedy on screen and feel awful about it, especially since it is based on a true story. However, more importantly, we can always stop watching. We know the character’s life is not our life. The film makes it clear that we are privileged observers, looking on from far away, and we should be grateful for that.

Beautifully written. I’m definitely watching this again.

Thank you, Zach!