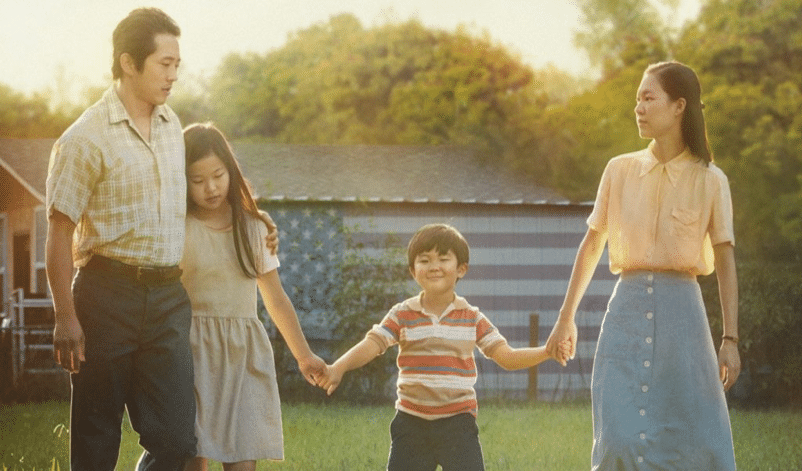

YOLANDA NOSAKHARE WRITES — At a time when hate crimes against Asian Americans are soaring across the US, the arrival of director Lee Isaac Chung’s film “Minari” hit theaters in the nick of time. The film’s storyline follows a first-generation Korean-American family’s experience moving to Arkansas in the 1980s. They move to the U.S. with hopes of building a life through the father’s purchase of a farm. From the beginning, they deal with culture clashes and financial difficulties.

“Minari” was released in 2020 to streaming platforms but has recently come into the spotlight, with a big screen debut that amassed rave reviews, in part because viewers of all sociocultural backgrounds see a piece of themselves in this film.

Here’s how. The two-hour drama begins with the Yi family moving into a trailer home, or “fun house on wheels,” as the grandma refers to it. The parents start jobs as chicken sexers to fund the father’s dream of building and running a 50-acre farm. The mother of the family finds herself conflicted between supporting what seems like her husband’s pipedream and living in suburbia on the money they’ve already saved. While this may be a typical dilemma facing immigrant couples, middle-class working families also live in this sort of limbo, having enough to survive but not enough to feel secure and comfortable or to dare to dream for bigger and better things.

Watching the cinematic Yi children— David and Anne — navigate their dual identity crises is another experience that many Americans can relate to. Whether first generation or not, surely, we can all remember the anxiety of being the new kid in a neighborhood, at school, or even at church. The Yi kids are greeted at their predominately White church with some laughably ridiculous questions and statements by the other children, like John, who asks David why his face is so flat. Another kid utters a bunch of gibberish and asks David’s sister Anne to stop her when she finally says something Korean. Still, the children form unlikely friendships. John even teaches little David how to chew his dad’s tobacco!

There are so many heartwarming bonds in “Minari,” but my favorite is the one forged between David and his grandmother. David at first had trouble connecting with his grandma because he felt that they were worlds apart. He made this clear with statements like “grandma smells like Korea” and “she’s not a real grandma” (his evidence being that she didn’t know how to bake chocolate chip cookies). While most of these exchanges are humorous, the grandmother/grandson relationship also parallels those formed by people from different sociocultural backgrounds who struggle to find their commonality. There’s always going to be a learning curve at the intersectionality of two cultures, and “Minari” demonstrates this tastefully.

Director Chung’s film is a must-see for every person who has ever dared to dream. It’s a heartfelt reminder that we are all more alike than different, and that our differences simply serve to make us unique-not opposites.

The surge of hate crimes against Asian-Americans in the Covid-19 era is the result of ignorance about Asian Americans. “Minari” is a much welcome cinematic antidote.