ALEXANDER SMITH WRITES — I found myself on a plane home just two days after LMU announced it was closing down campus and moving to virtual learning. However, home for me was not the usual house or apartment, it was a hotel in downtown Houston. My dad has been in the hospitality business for 35 years, and up until this point I had moved eight times throughout my life, while my dad managed numerous different Hyatt hotel properties. I was used to the “suite” life. Having spent most of my childhood growing up in a hotel, I always had close relationships with the employees and saw how my dad conducted himself at work up close.

But the normal suite life turned sour quickly when I returned, and soon, COVID had turned my home life into a personal hell for me and my family.

What first hit me was the silence. There was no doorman or front desk receptionist to greet me on my return. The bar and restaurant in the lobby were completely roped off and silent. Billy’s shoe shine stand already had a thin layer of dust covering both seats. I had expected and known about this, but seeing it in person was indescribable. It felt like I had walked into an ominous abandoned mall. I learned just how bad the situation was later that night in the hotel room. While I sat on the couch distracting myself with TV, I saw out of the corner of my eye my dad sitting at the kitchen table staring straight ahead. His martini was untouched, going from ice cold to room temp, and he hadn’t said a word in hours. My friendly pat on the back and “what’s up dad” was met with an empty and sad expression akin to when he had told me his dad had passed away: “I had to let them all go. All of them. Fired. I had no choice.” He wasn’t even looking at me. I had seen my dad cry twice in my life, both over family deaths, and I could tell he was trying to hold it in. “I know man. I’m sorry,” was all I could muster for a response.

The only employees who remained were my dad, a few engineers to keep the hotel from falling apart, the director of operations and three house keepers who were on call. I later found out that the housekeepers that got to stay were based on seniority and how long they had been working with the company, meaning they were all minority women over 60 years old — the demographic most vulnerable to the virus.

The very next morning I was up early with my dad eating breakfast. I had trouble sleeping, I hadn’t realized how comforting the usual hotel noises of elevators beeping outside our room and people talking in the hallways had been. We didn’t have to strain our ears to hear the CNBC money show give the morning report.

“… and with the opening bell the market is open for another brutal day of losses. Hospitality stocks are being hit especially hard, Hyatt Hotels Corporation is today’s leading loser, currently down 38%…”

In the span of just over a week, Hyatt’s stock price had dropped from over $90 a share to a low of $28. My dad didn’t say a word as he got his coffee and walked out the door. This is a reminder that many companies suffered more losses than they had to due to short sellers and hedge funds betting against them during a pandemic and driving their stock prices down.

I still feel that people have no idea just how bad COVID hit hospitality. During the worst of the 2008 financial crisis, hotel occupancy was between 20-30%. Nearly all hotel occupancy rates were at ZERO for the majority of the pandemic. Furthermore, 70% of the hospitality industry is actually comprised of small businesses. While this Hyatt location would survive, many family-owned hotels and motels were shutting down across the country. Hotels learned to operate with a staff that was 1/10th the size it used to be, rendering many positions useless for a potential post-COVID comeback. The industry will never be the same.

I began to feel a self-guilt of privilege as I helped my dad out by working as security and a greeter for the hotel. I understood that the employee whose shoes I was filling would be getting paid more from unemployment. Why would they choose to come back and void their unemployment status for extremely limited hours? But I felt bad for maintaining this small job while hundreds of former employees were at home figuring out how they were going to pay their bills and afford food for their family.

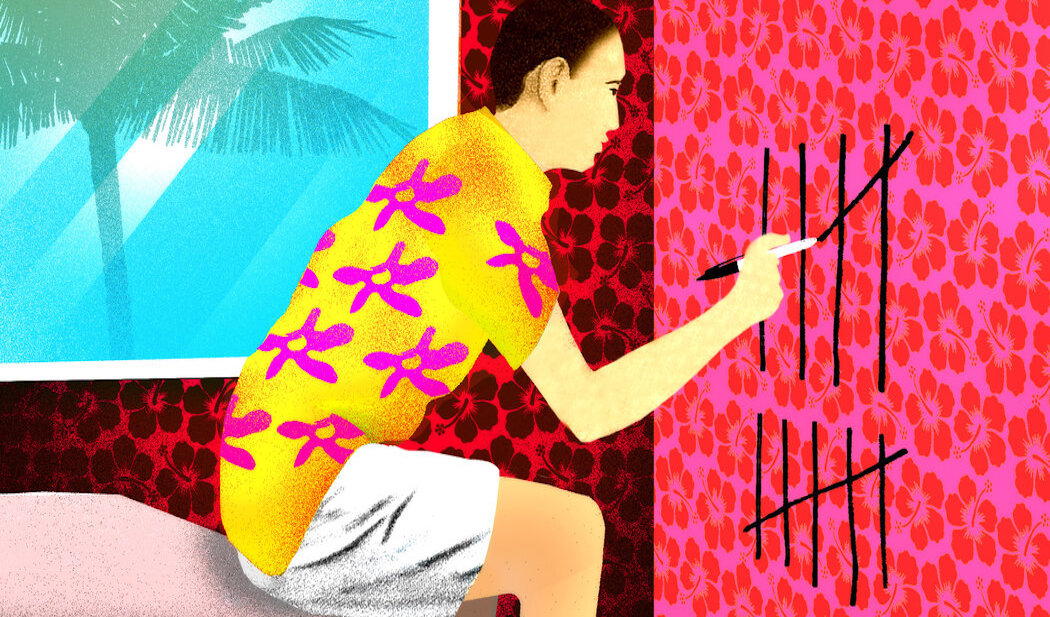

We peaked at 5% occupancy the entire summer. My security job began to take a toll on my mental health, as I worked alone for long periods of time. Every downtown area in America has a severe homeless epidemic, and I had to turn away mentally ill people experiencing homelessness by the hour. The occasional guest would be frustrated at the lack of hotel amenities, and by the fact that the person had to wear a mask. Basically, anyone trying to visit the hotel at this point didn’t understand that we were in a global pandemic or just didn’t care.

The COVID quarantine in a hotel was an entirely different experience than in a normal home, and I hope the country and the world takes the necessary precautions, so that no person or business has to experience this again.

LMU student Alexander Smith is an Asia Media staff writer.