ELLA KELLEHER WRITES (latest in her review series of new Japanese books) – How does a global war affect regular people caught in its wake of devastation? How long do those effects linger on and how should a society react to them? Shaw Kuzki’s heart-wrenching tale, Soul Lanterns (2021), aims to answer these questions with an explosion of powerful vignettes that describe the lives of Japanese civilians living in Hiroshima, Japan and their connections to the nuclear bombings that occurred there during World War Two.

Soul Lanterns offers very authentic authorship. Shaw Kuzki is a second-generation A-Bomb survivor who encapsulates the generational trauma created by the bomb in concise and meaningful language. Kuzki’s novella provides the personal depth necessary for a truly emotionally and socially impactful read. Kuzki’s mastery is made even more powerful by Emily Balistrieri’s incredibly precise and vivid translation of story.

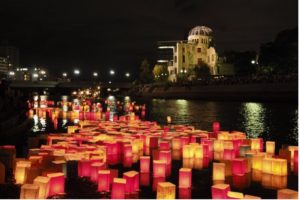

It’s August 6th, 1970. Nozomi, a twelve-year-old girl living in Hiroshima is expected to attend the lantern-floating festival with her mother to honor the people killed by the atomic “flash” and its after-effects. In colorful paper lanterns, people write the names of those they lost and set them afloat on the river, allowing them to “shine their light on the dark water” as the “lanterns and souls roll along together.” The purpose of this ceremony is to allow the souls to metaphorically pass into the void in a beautiful, somber fashion with their loved ones watching them move on in peace. Thus, the lost souls can have some closure – the very thing that the “flash” robbed them of.

Nozomi watches as her mother releases two lanterns. The first is dedicated to Nozomi’s father’s first wife, Kumiko, who died from burns inflicted by the bomb while working out in the fields. The second is an ominous white lantern, with no dedication except for a blank strip of paper neatly folded inside. During the festival, a mysterious older lady approaches Nozomi and frantically asks the girl’s age, then with a disappointed look asks the age of her mother. Tearfully, the older woman walks away and leaves a dumbfounded Nozomi to deal with two mysteries: who is the white lantern for? And for whom was that older woman searching?

Coinciding with the festival, Nozomi and her classmates are tasked with an art project in school, where they must construct a creative piece that in some way tackles the effects of the A-Bomb. Their handsome and eclectic art teacher, Mr. Yoshioka, requests that each student focus on a particular nyushi hibaku — or someone who had experienced the bomb firsthand, also referred to as hibakusha.

Unbeknownst to Mr. Yoshioka, Nozomi decides to focus on the story of him and his deceased girlfriend, Satoko. On one fateful morning twenty-five years ago, a younger Mr. Yoshioka stood by the window of his art room, painting a scene outside when his girlfriend Satoko inquired as to why he paints natural imagery. The young Mr. Yoshioka snaps at the girl in response, and instantly regrets it. Satoko runs away before Mr. Yoshioka could apologize. He looks out the window in panic and sees Satoko, trudging through the field in front of the school. Mr. Yoshioka explains that “that was the last time I would see Satoko. And all I could find of her after the bomb fell was [her] scorched comb.” This small comb with little carvings of rabbits became the only part of Satoko that Mr. Yoshioka could bury.

After the atomic blaze swept over the city, Mr. Yoshioka frantically dashed toward the city center where Satoko would have been. During his search, he risked incurring permanent radiation damage to his cells which would damper his health for the rest of his life. Mr. Yoshioka would spend the remainder of his adulthood repainting the image he saw from outside the art room on that day: a lush, green field where he last saw Satoko. This short narrative reveals how the A-Bomb’s effects on people are two-fold: the “flash” and subsequent radiation severely physically injured and killed its victims, and it also left an everlasting psychological scar that would come to haunt them for generations.

Nozomi’s classmate, Kozo, would learn that his paternal aunt, Sumi, suffered a similar fate to Satoko. Supremely kind and innocent, Sumi was prone to overwhelming acts of empathy. During the height of the war, she fed stray cats and dogs and sheltered them from the outside world’s brutality. Sumi aspired to be a teacher, and the year the bomb hit she got her first posting in central Hiroshima. After the bomb dropped, Kozo’s grandfather hurriedly went into town in search for Sumi. He scoured the demolition site of Sumi’s school and found only a skull surrounded by smaller skulls in what was once her classroom. Written on a small sign nearby the grim site was “R Girls’ School teacher and students. Burned to death.” A quarter of a century after Sumi’s death, “[Kozo’s] grandfather and the others were still waiting for [her] to come home – even if they knew logically that she wouldn’t.”

These short stories about Sumi, Satoko, and others like them prove how war does not just devastate its initial victims, but also their families and later generations who are told about the brutal way in which their forbears died. Whether it’s the local widow who has been unable to speak for years out of trauma, the mother of a deceased schoolgirl, or a mother who cannot find her son – everyone in Hiroshima has a story about the A-Bomb, a point that is made powerfully clear by Kuzki’s work. Mr. Yoshioka wisely says, “This world is made up of little stories. Those modest daily lives, those lives that may seem insignificant, they give the world shape – that’s what I believe. Don’t you think that presenting small stories in detail is precisely the most certain way to depict huge things?”

Kuzki’s novella poetically depicts the primary effects of the A-Bomb, and how they linger on for decades, but what is implicitly communicated in this work is exactly how a society should react to the hibakusha. For many Hiroshima survivors in Japan, there is great stigma surrounding their experiences and existence. Many Japanese civilians after the war ended erroneously believed that those dealing with radiation sickness were somehow contagious. As a result, the hibakusha became social pariahs who were unable to be married or hired, leaving them utterly abandoned. This stigma extended to the relatives of the hibakusha, which would include girls such as Nozomi. Kuzki’s work humanizes the hibakusha by intricately detailing their stories, pain, and ongoing suffering. The novella itself is a testament to the prevailing human capacity for empathy.

Soul Lanterns ends on a socially important note with relevance to today’s discussion about how Japan must openly recognize its past wrongdoings that escalated the Second World War and its bloodshed. In a letter to his students, Mr. Yoshioka states that “We Japanese people, whether we like it or not, became aggressors in that miserable war. We also became victims. Both our crimes and our wounds are vast and profound.” Kuzki’s book puts forth the duality of the post-war Japanese identity – that of being both villain and victim. In a way, Kuzki gives us a way to move past this dilemma through Mr. Yoshioka’s letter: “Thou shalt not be a victim, thou shalt not be a perpetrator, but, above all, thou shalt not be a bystander.” More than anything, the novella argues that future generations in Japan must never again idly stand by and watch while others suffer. This is why Kuzki’s story of Hiroshima and the hibakusha are so important – it is a reminder to never again allow such acts of human cruelty.

Recent LMU graduate Ella Kelleher is the book review editor and a contributing staff writer for Asia Media International. She studied English with a concentration in multi-ethnic literature.

Wow, Ella has done it yet again. Another incredible review, in fact these are the only reason I wake up in the morning.

Heartfelt and well written review of a heartbreaking story. Thank you, it’s on my list to read