TOM PLATE WRITES — There are always concerns about Japan, with its background of not only brilliant accomplishments but also unforgettable aggressions; but now that Japan is in the foreground again, if with cheerless Olympics, historic debt and China rise, who can be sure what’s next? Recall that the geopolitically pivotal region of East Asia began its major transformation in the mid-sixties, when Japan’s wildly successful Tokyo Olympics proved an early marker of its emergence as an economic powerhouse. This was at the same time Mao’s China was still reeling from the Great Leap Forward that triggered the greatest recorded mass famine in history. By contrast, by the eighties there were times when it seemed as if the Japanese could afford to buy almost anything anywhere (such as America’s Rockefeller Center), whereas across the East China Sea not many Chinese seemed to have any money to buy much besides bags of rice. And all this was not so very long ago.

Fast-forward to today’s Tokyo Olympics, eviscerated by a prowling pandemic into little more than an international TV event — the great citizens of the colorful Tokyo metropolis mostly off-camera in a new state of emergency; and the nation’s economy sagging under a Mt Fuji of debt, the product of inept government that since the 90s seemed to lack what its over-regulated business community had in excess: ideas that worked.

Even though Japan’s economy still weighs in at number three – still leading Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and India — the sense of stasis is unsettling. Japanese note the seemingly effective and polished centralized direction from Beijing, as well as the concessional measure of entrepreneurial decentralization, as factors behind China’s roaring economic charge into the 21st century. Might in the economic regard Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) deserve less respect than the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)? This rankles. But change happens. The central government in Tokyo and the nation’s business and entrepreneurial community are culturally Japanese to the core, to be sure; but the renowned secular consensus-unitarianism no longer offers magnetic appeal. And so at almost every opportunity, the business community is finding ways to polish its act and regionalize, leaving the LDP-led government in the rust.

Perhaps no scholar has analyzed this extraordinary bifurcation more cogently than Professor Satori N. Katada, of the University of Southern California: “Japanese foreign economic policy is moving into unchartered territory,” writes this careful scholar in her book Japan’s New Regional Reality (Columbia University Press): “The distance between the Japanese government and big business has widened significantly since the mid-1990s.… The government machinery is struggling to keep up.” Not unlike Beijing, Tokyo had preferred to conduct trade relations one-on-one with other countries. But Japan’s private sector seems more at home than ever with multinational constructs and regional arrangements.

This dynamic has the potential to convert Japan into a leading cosmopolitan economic actor. This was already in motion when the Trump administration unceremoniously dumped the Trans-Pacific Trade Pact (TPP) and the Japanese filled it, to the consternation of narrow-minded Trumpsters. Notably, China was not a TPP member and had no plans to be one; Japan’s zest offered quite the contrast with Washington’s petulance. (Smartly, the Biden economic crowd wants back in.)

Japanese thinking about regional economic deal-architecture could stand out. In China, the Xi Jinping regime continues to suck space away from prominent entrepreneurial leviathans; in the U.S., the White House seeks to call to account those parts of the nation’s business sector that it deems insufficiently public-interest minded. A rough parallelism could be noted. But in Tokyo, informed people are asking whether “the state’s interventionist role and its ideology live beyond its usefulness,” as Katada deftly frames it. For Japan, the willingness to accept – even seek out – global standards of institution building and rule setting might be said to reflect a final rejection of past provincialism and a new referencing of the global cosmopolitan playbook.

Might China someday also sign on to a liberal economic coalition? The safe prediction, of course, is that China, under Xi Jinping, feels that it can say ‘no’ to anything that has a Western (or un-Communist Chinese) feel. And perhaps that will remain so. But intense contacts with the outside world to keep a gigantic economy buoyant can have its own unintended internal effect. Surely over time, outside voices have already impacted Japan in ways its forefathers never could possibly have foreseen. Perhaps China will become more like Japan?

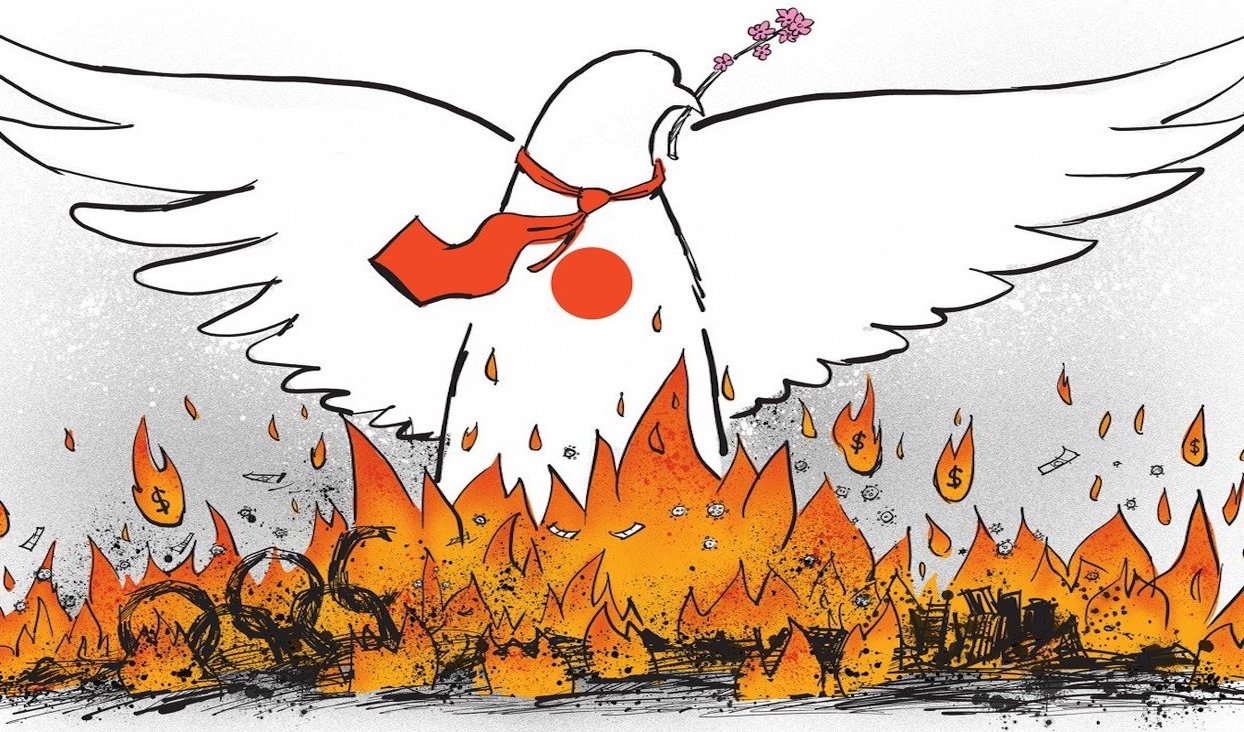

In my hopeful Pacific scenario Japan is envisioned as evolving an Asian ‘third way’ that adds to peace and security: A deep culture with an astronomical literacy rate reads the tea leaves of the future not by recoiling but by dynamically evolving. Its precarious but influential position between China and the U.S. becomes not just an annoyance or threat, as far as Beijing is concerned, nor just a reliable adjunct offset to China, as far as Washington is concerned; but for the region provides an invaluable non-ideological psychology for coping with reality. Yet, this is optimistic, at a juncture in history when optimism is not rampant in the Land of the Rising Sun.

I accept that if you support Japan taking a more assertive role in any way, you run the risk of having people feel you suffer from serious memory loss. Or that some Japanese do: for example, offering to help the U.S. defend Taiwan is most definitely bad neighbor policy for Tokyo. A progressive geo-economic evolution may well be just what the region needs; re-militarization is not. Only a fool underestimates the Japanese; but it’s a fool’s errand to bait Beijing, particularly over Taiwan. Japan does best and offers neighbors its best when it keeps its military on a leash while unleashing its impressive entrepreneurial powerhouses. I hope it sees that clearly.

Clinical Professor Tom Plate, author of the ‘Giants of Asia’ book quartet (Marshall Cavendish International), Loyola Marymount University’s Distinguished Scholar of Asian and Pacific Affairs and the Pacific Century Institute’s vice president, is a regular op-ed contributor to the South China Morning Post, where this column appeared earlier this week.