BOOK REVIEW EDITOR-IN-CHIEF ELLA KELLEHER WRITES – In times of darkness, when all seems hopeless and lackluster, South Korean author Baek-Sehee’s mind often conjures up countless questions to inspire faith: What about the people that love you? What about the millions of possibilities where things can get better? And perhaps most importantly, don’t you want to eat tteokbokki again?

Korean author Baek-Sehee has her whole life ahead of her. She works as a successful young social media director at a publishing house where her boss seems to genuinely care about her. Yet, despite her loving friends and doting family, she finds herself at a loss. She feels depressed, constantly running low, feeling anxious, and self-conscious. On the outside, she cultivates a perfect porcelain mask for her loved ones, who are not at all aware of the agony she endures. To find answers, she decides to consult a psychiatrist. What’s wrong with her? Such turmoil can’t be normal, right?

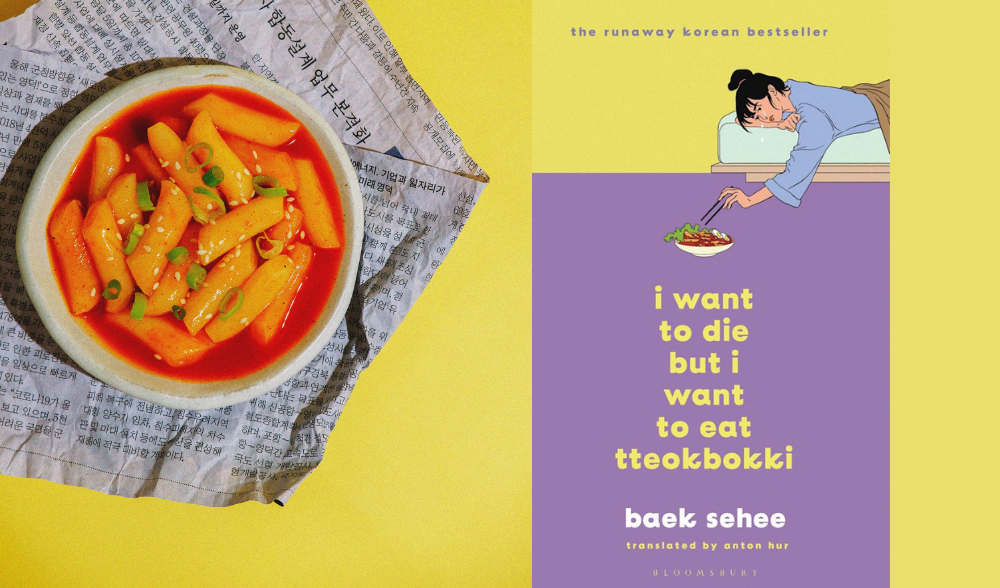

I want to die but I want to eat tteokbokki (2022) is Baek-Sehee’s phenomenal blend of memoir and self-help book that has quickly become a Korean bestseller, recommended even by a BTS member. Korea is notorious for its blasé attitude toward mental health importance and its highly stressful work and social environments, a known factor in youth suicides. Baek-Sehee’s latest book wants to shed the protective curtain over mental health issues that have stigmatized this ongoing epidemic. Weaved seamlessly into English by translator Anton Hur, I want to die but I want to eat tteokbokki is both inspiring and eye-opening as we step into the mind of a tormented individual who we cannot help but relate to.

Living and working in Korea myself, possibly the most comforting Korean snack one can indulge in at any hour of the day is the chewy, sometimes spicy rice cakes called tteokbokki. In her lowest moments, Baek reaches for a plateful of this familiar comfort which in turn wraps her stomach in a warm, nostalgic hug, tempting her to stay on this Earth a little while longer.

Baek is quickly diagnosed with a persistent case of depression, also referred to as dysthymia, by her psychiatrist. Baek describes her condition as feeling “hollow,” a world in a permanent state of blue-hour where she feels “obsessive worry” over how others perceive her actions and appearance. Baek records her twelve-week sessions with her psychiatrist to combat her “memory block,” which can happen in times of stress and high intensity. Afterward, Baek pursues a decade of therapy to grapple with her mental health. In her time of reflection, she decided to compile the recordings for her book in an effort to reach out to an audience that may need it.

Food brings Baek a great deal of joy – this is something we can all relate to. However, being a young South Korean woman entrenched in a highly gendered and looks-driven society, she feels guilty about her coping mechanism. Baek recounts her struggles with disordered eating and binge-eating disorder. Her thoughts spiral out of control, unraveling in a dark, twisted mess before her psychiatrist: “They hate me. I’m hideous.”

Baek, to some degree, is aware of how social media and modern society play into her already fragile self-image, putting pressure on the already-there cracks and fissures. Baek explains, “I want to love my own face, but I like other faces so much that I can’t look pretty to myself.” The simplification of human beings is perhaps one of the most heinous symptoms of widespread social media usage. We are not simply ugly or beautiful – it’s never that simple. Subtly, the psychiatrist touches on this illusion when explaining that “the people whose faces you like are probably beautiful, and the faces you don’t like can be beautiful, too.”

Baek’s valuable writing helps normalize anxieties and stresses. This powerful book is Baek’s catharsis, a pouring out of her heart and mind onto pages that remind the reader that we are not damaged or fatally flawed at all. Feeling imperfect and depressed is a part of the impossibly complex fabric of the human experience.

Baek’s story does not end with a “cure.” She does not finish this story by claiming she had been erased of her depression and anxiety. She discovers that there is no “cure,” no god pill, or mind-mastering psychiatrist who “fixes” her. In the end, she simply continues on an ever-evolving journey of self-love and personal growth. Perhaps the greatest message of this book is to seek others in our time of need, to reflect on our pain and suffering, and to find comfort in the simplest pleasures like sticky, fried rice cakes.

LMU English major graduate Ella Kelleher is the AMI book review editor-in-chief and a contributing staff writer for Asia Media International. She majored in English with a concentration in multi-ethnic literature.