TOM PLATE WRITES — Chinese authorities who fret about a Cold War with the U.S. might also want to analyze – unemotionally – another possible threat to domestic tranquility: a kind of brewing ‘cold’ war between the genders – at home, upfront and personal. One vista of future shock was available to Beijing recently week If it bothered to watch the televised U.S. Senate hearing on the nomination of Judge Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court, America’s highest jurisprudential perch – with a lifetime appointment no less.

Opponents as well as supporters almost came apart emotionally; the national psyche was revealed to be more than mildly disturbed. The stormy vetting process of the seemingly blue-chip Kavanaugh (Yale Law School, etc) was triggered, initially, by a single sexual assault allegation, which testimony by the alleged woman victim was taken by liberal opponents of the politically conservative lower-court jurist as positively probative – and by conservative supporters as positively partisan.

Even so, the Yale-educated lower-court justice squeezed through and has been sworn into office. But something like half the rest of the country felt squeezed out – and yearns for revenge. (Call it a sequel to the infamous 1991 Clarence Thomas/Anita Hill Senate Judiciary Committee hearing drama that still haunts today.) A showdown could come next month, when biennial elections will determine whether the Trumpian Republican Party is to retain its reign on America’s powerful bicameral national legislature.

The mistreatment of women by men – or, in the elevated terminology of modern feminist sociology, the ethical structure of patriarchal society – was the emotional doppelganger, as it were, for the ambushed Kavanaugh. It’s simple: Just as Marx insisted that capitalism was a toothpick house of inherent contradictions that would eventually collapse, so today’s feminists view patriarchy as a doll’s-house of inherent injustices and unsustainable norms that no longer make sense. Patriarchy inevitably metastasizes into misogyny, then hardens into sexist authoritarianism.

China, as if in ping to American pong, is feeling feminist pressure, too. If viewed in the U.S. as combative– for its advocacy of dismantling male hierarchies for a more gender-inclusive, even non-gender-normative deviarchy (escape from the prison of official or cultural oppression) – China has so far appeared to stamp it as a plain old counterrevolutionary sin. Even the All-China Women’s Federation, founded in 1949 in comity with the Communist Party’s endorsement of gender equality, thinks of the current feminist flutter as part of the problem, not the solution. Like the Republican-controlled Senate’s partisan bias toward Kavanaugh, the ACFW serves far more as echo of the political establishment than critical women’s voice.

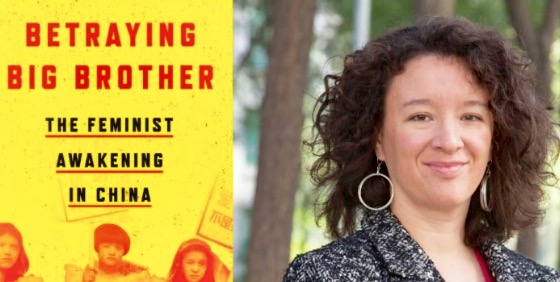

But if China’s feminist movement is able to reach the hearts and minds of the country’s labor-rights movement, for example, a large-scale collaboration with working-class women could be viewed as a threat to stability. The pioneering journalist Leta Hong Fincher, author of the 2014 ground-breaking ‘Leftover Women: The Resurgence of Gender Inequality in China,’ has in her just-published second book, ‘Betraying Big Brother: The Feminist Awakening in China,’ concluded this: “Most analysts of China’s authoritarianism regard gender as a marginal issue, but I believe the subordination of women is a fundamental element of the Communist Party’s dictatorship and its ‘stability maintenance’ system (weiwen)…. Xi Jinping … sees patriarchal

But how can this be? Feminist concepts are hardly new to China. The young Mao Zedong himself blasted China’s traditional arranged marriage system as a feudal relic – as a relationship of daily rape. And this thought from the young Mao came in 1919! But – as the saying goes – that was then, and this is now. The loyalist ACFW argues that Chinese feminists have so broadened the women’s rights definition as to play into the hands of foreign elements that wish to destabilize the country any way they can.

This is to misunderstand the power of an idea. The feminist instinct has spread to many countries now calling for change. In Saudi Arabia women can drive cars, etc. Deviarchy is big in its philosophical sweep, bigger than any one nation state. Large ideas in history are like that; feminist anger travels with or without a visa across our borderless world with relative impunity. With China, the conveyor of subversive feminism is not the CIA but the Internet. Without it, female (and male) feminists could not link up and connect. Even with the government’s prodigious oversight, content communication, often coded, is not that hard to pull off, especially in a nation that has more Internet users than the U.S. has people. Instead of gathering on street corners in protest for all to see, Chinese women exchange ideas and make plans behind blockchain curtains, as it were. The Chinese government should not feel that it’s being targeted in the cross-hairs of foreign feminist hit squads. The feeling of being repressed or gender side-lined comes from deep inside, not from far way. What is unfolding is an international cultural revolution, not a Chinese one.

If anything, America’s dual-party politics seem no more fitting or subtle a system in the face of a gender revolution than a one-party system. The latter may rely on political repression, the former on political division: But over the long run neither seems destined to prevail. Consenting to the controversial elevation of Judge Kavanaugh to America’s highest court may have been a just decision purely on the jurist’s resume-merits, but it may also have been precisely the wrong move for the country. Sometimes the cause transcends the individual: “If we want things to stay as they are”, declared Giuseppe di Lampedusa in his great historical novel The Leopard, “things will have to change.” Neither country’s systems are supple enough change-agents when it comes to gender justice.

Columnist Tom Plate, author of the recent ‘Yo-Yo Diplomacy’ and the four-book ‘Giants of Asia’ series, is Loyola Marymount University’s Distinguished Scholar and the Pacific Century Institute’s vice president. He is founder of Asia Media International. A similar version of this column was originally published in the prestigious South China Morning Post on 11 October.