KHON KAEN, THAILAND — When business started to sag a year ago at the shoe factory where she and her husband work, Nui Kalathai began to borrow money from relatives in her village in Khon Kaen, one of the largest provinces in Thailand’s northeastern plateau. She has been careful to ask for only small sums — 400 baht ($12.60) one day, 200 baht on another — to help cover daily expenses like eggs and dry rations. “It’s so hard to survive with little cash,” says Nui, who has a 10-year-old son. “I also have borrowed from two money lenders in the factory.”

Nui’s family is not the only one feeling a cash squeeze. In Chai Nat, a rice bowl in Thailand’s central plains, and Phatthalung, a palm oil and rubber-growing province in the south, conversations often turn to financial hardship with little prodding.

Somsak Thangphon, a rice farmer, expects to reap more losses than rewards from his ripening green paddy field shimmering under the late morning sun in Chai Nat. With rice prices hovering between 6,000 baht to 7,000 baht a ton — his best years were between 2011 and 2014, when government support pushed the price to 15,000 baht per ton — he is barely able to cover his costs. Somsak has drained his savings and now lacks the cash needed to cultivate his crop of white rice. It is no different for rubber — a key product for Thailand, the world’s largest producer and exporter of the commodity.

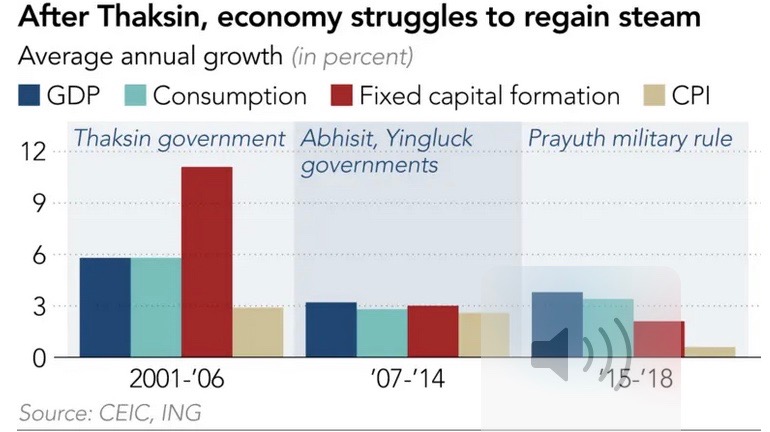

For many in Thailand’s rural heartland, life has become harder under the junta that assumed power in 2014. Now, as Thailand heads toward its first post-coup election on March 24, it is the country’s factory workers and farmers — including nearly four million rice-growing families — who appear to be shaping the terms of the political debate.

Thailand’s poll, which has been delayed five times by the junta, will mark the return to a semblance of democracy after nearly five years of military rule. Confidants of the generals are hoping voters will focus on what they regard as their greatest success: restoring political peace in a deeply polarized country. But it is the junta’s economic record that is foremost on the minds of the majority of the voting public, who have watched as Thailand became the world’s most unequal country during its rule. Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha, the gruff junta leader, is nonetheless campaigning on a message of stability as he seeks to become the head of an elected government. A 157-page book detailing Prayuth’s record echoes his promise to “return happiness to Thailand,” a pet theme ever since the powerful former army chief staged Thailand’s 13th successful coup since the absolute monarchy ended in 1932.

The coup put a lid on nearly 15 years of political clashes between two broad camps, one drawn from the well-heeled, ultra-royalist elites concentrated in Bangkok, and the other from the economic have-nots and struggling middle classes in the rural north and northeast. The latter group has remained staunchly loyal to former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, who lives in exile.

Those old political divides burst into the open again in February, when a new political party supported by Thaksin nominated Princess Ubolratana, the older sister of King Maha Vajiralongkorn Bodindradebayavarangkun, as its candidate for prime minister. The nomination of the princess was typical of Thaksin’s penchant for seeking to undermine the junta, whose leaders have emphasized their loyalty to the palace. But her candidacy was rebuked only hours later by the monarch, and the princess quickly withdrew her name — leaving the fate of the Thai Raksa Chart party that backed her hanging in the balance. This unusual episode has added to lingering questions over whether the election will even be held at all….

Excerpted under ‘fair use’ international copyright rules from the original article in NIKKEI ASIA REVIEW. https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Cover-Story/The-99-election-Thais-are-worse-off-after-five-years-of-military-rule