ELLA KELLEHER WRITES (in the third of three reviews of new Japanese books) – Oyamada’s protagonist is not much different from Alice who fell down the rabbit hole. As Asahi descends deeper down the chasm, reality itself tears at the seams and breaks open, folding in all around her.

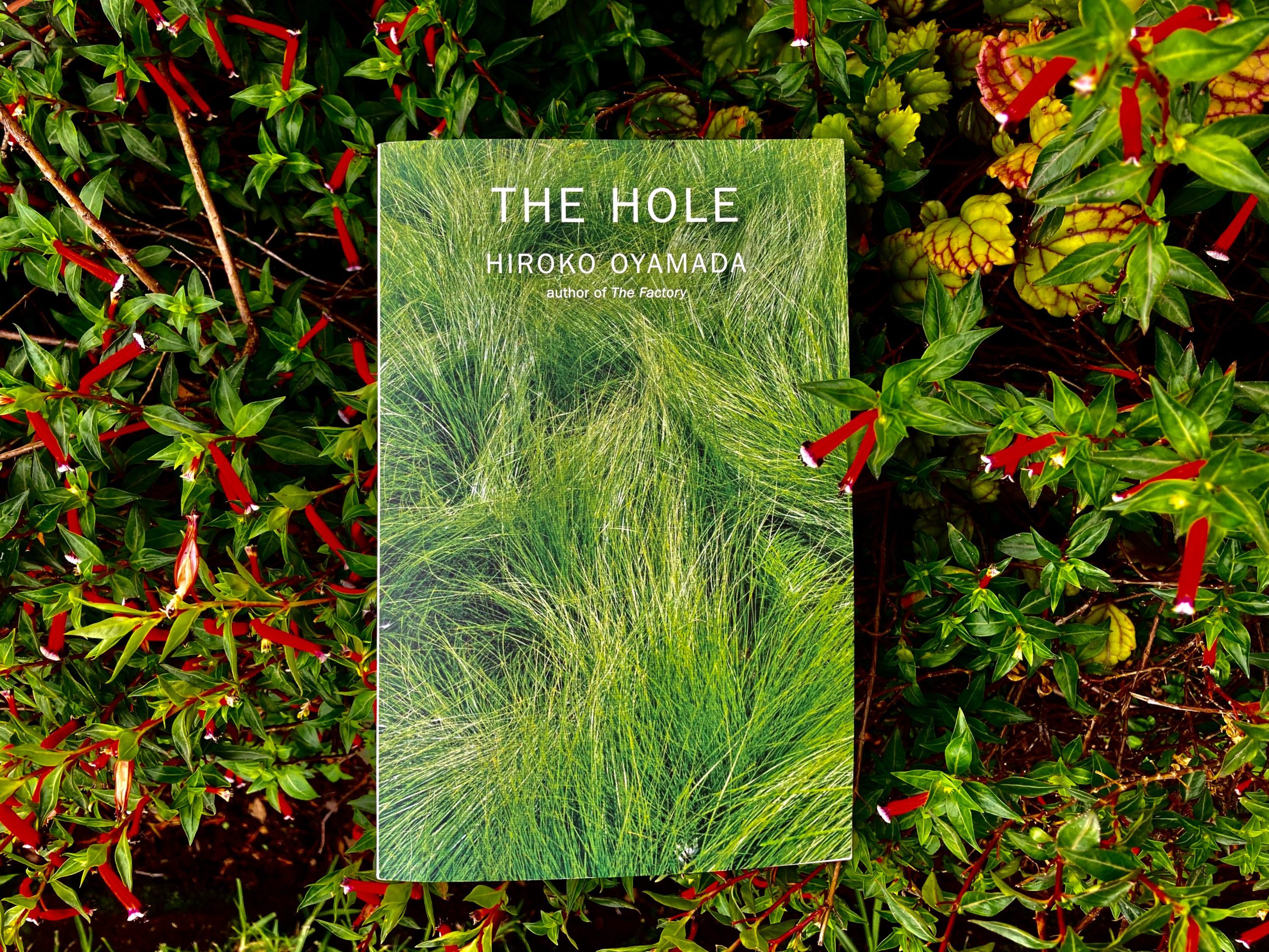

The Hole (2020) is the second novel written by Oyamada to be masterfully translated into English by David Boyd. The Factory (2019) was Oyamada’s first novel to grab the attention of international audiences. Both tales use similar narrative techniques which leaves many unanswered questions. The Hole is a profoundly deep reflection on the condition of Japanese society and the constraints it places on its people.

While reading this head-spinning novella, it is not always clear what exactly is happening. Hiroko Oyamada’s atmospheric writing conveys a sort of existential dread and emptiness and doesn’t prioritize linear storytelling, compelling the reader to ask questions: “Where is Asahi going? Is the droning of the summer’s cicadas ever going to end? Or is it all in her head?” But by the time the reader notices how mysterious and confusing the tale has become, they’ve dug themselves too deeply into this surreal, magnetic literary landscape to turn back.

The story itself is captivatingly mundane: a twenty-nine-year-old woman named Asahi Matsuura quits her “non-permanent” job because her husband, who has a “permanent job,” is being transferred to the bucolic town where he was raised. Asahi is reduced to a housewife and lives next door to her in-laws. Asahi’s husband remains largely absent throughout the story, creating quite a gap for his wife and other characters to occupy.

Asahi’s tone as a narrator is excessively passive, the writing itself is rife with short sentences and quiet dialogue alongside deadpan descriptions of everyday things. Despite the overwhelming realism in the beginning, Oyamada inserts unusual bits and pieces to let the reader know that this story packs a twist. In one scene, Asahi admits that she does not know that her husband’s parents own a second home. She herself reflects that, “[she] must have seen it when visiting,” but confesses that she cannot “conjure any memory of the place.” This small mystery – the inability to recall what one must have seen – plants the footing for major mysteries later on.

In the same detached voice, Asahi agrees to give up her role as a working woman and becomes a stay-at-home-wife. Here we can see how The Hole concerns itself with the issues of women in Japan as it highlights the rigid expectations Japanese women must face. Asahi is only referred to as “the bride” by her new next-door neighbors, simplifying her existence to her marital status and how well she plays her gender role. With such an overabundance of free time, Asahi feels suffocated. She admits that she was “pretty sure [she’d] get sick of [her] new routine within a week – but it only took one day. Every day after that was as mind-numbing as the one before, ad infinitum.”

Suddenly, The Hole drifts into the realm of the surreal and dreamlike. In a pivotal scene, Asahi goes on an errand-run to a local 7-Eleven and sees a strange black animal along the riverbank. Out of nowhere, she falls into a five-foot-deep hole. Trapped and swallowed slowly by a ditch that might flood with underground water, Asahi watches as a beetle floats past her face, listens to cicadas shriek all around, and observes black and red ants flow like veins of the living dirt. A little while later (though no exact time frame is given), a middle-aged and well-dressed neighbor named Sera helps wrench Asahi out of the mud and grime. Sera ominously asks, “You’re the bride, aren’t you?” It seems that the “hole” is far more than something literal – it also encompasses the figurative terror of society’s smothering roles for men and women.

Asahi finally makes it to 7-Eleven, where she meets a man claiming to be her brother-in-law playing with local school children. He is a hikikomori (shut-in) who has been living alone in his parents’ tool shed not far from their family home. I wondered myself whether this character is real or not – and that is never made entirely clear – but what is clear is the growing problem of Japan’s youth becoming hikikomori, modern day hermits who reject society and usually reside in their family homes for the rest of their lives.

The Hole humanizes the dehumanized. When the brother-in-law explains why he became a hermit, he says, “families are strange things, aren’t they? You have this couple: one man, one woman. A male and a female, if you will. They mate, and why? To leave children behind. And what are the children supposed to do? Turn around and do the whole thing over again? Well, what do you do when what you’ve got isn’t worth carrying on?”

Asahi is aggressively questioned by the brother-in-law who is unimpressed by her story of falling into the hole: “This run-of-the-mill tomboy gets lost in her own fantasies – some big adventure, right?” The brother-in-law compares Asahi to Alice in Wonderland and asks her if she thinks he’s the white rabbit. Asahi then stops his badgering by pointedly asking him about the bizarre black creature. The brother-in-law responds with, “people always fail to notice things. Animals, cicadas, patches of melted ice cream on the ground, the neighborhood shut in. But what would you expect? It seems like most folks don’t see what they don’t want to see.”

The story continues in a dream-like fashion and Asahi, the dreamer, is not just the narrator – she is the only character. The only one who we know for sure is real, that is. As for the other characters, we will never know if they are or aren’t products of a vivid hallucination. The flatness of all the male characters reaffirms this idea – none are given actual names but roles like “the husband” or “the brother-in-law” or “the grandfather-in-law who always waters the garden even in the pouring rain.” Toward the end, the grandfather-in-law dies a perplexing, sudden death that cannot be rationally explained. Asahi decides to get a job working as a store clerk in the same 7-Eleven she met her brother-in-law in. She looks outside the store and sees nothing that she can recognize, “no animals, no holes, no children.” Finally, when she gets home, she looks in the mirror and is horrified to see the face of her mother.

Oyamada expertly molds the triviality of everyday life into a piece of remarkable literature – one that makes the reader ponder for days after reading it. The Hole magnifies the struggles of young adults in modern Japan, both men and women who feel lost in their assigned societal roles. Work and childrearing are boring and unappealing, and being a housewife is not a “summer vacation that never ends,” as the wives next door like to put it. What, then, is a person left to do when they cannot conform?

Amazing, Ella delivers yet another amazing book reviews. Now I have to get a copy of The Hole.

I recently finished reading this book and am binge-reading every analysis I can, to find any answers to all of my questions and hear others’ viewpoints. There is a statement in this article that I believe is untrue–at least for the English translation. It is mentioned that when Asa finally gets home, she looks in the mirror and is horrified to see the face of her mother. There is no indication that she is horrified as she looks in the mirror, and it is Tomiko she sees, not her own mother. The novel states, “When I got home and put on my uniform in front of the mirror, I couldn’t help but see Tomiko staring back at me.” Though a small detail, I think it is important to note the differences. Firstly, that it was Tomiko she saw and not her mother. Earlier in the novel, there was mentioning of Tomiko looking like her own mother-in-law, who Asa mistook as Tomiko’s natural mother. So, this distinction is thematic and if I had to guess as to it’s meaning, I would say it is symbolic of similarities of women who take on similar roles. It is not until she becomes a working woman like Tomiko, that she then sees herself like Tomiko. Secondly, there wasn’t note of her being horrified to see this face. Again, it’s a small detail but I think it is significant to point out that now Asa is accepting of her life and her choices– she found her role and has distinction. I am curious if this article’s writer made a mistake, or if simply this was written based off of the novel in it’s original language and if this is the difference of translation. I guess that’s what most of us who read translated books often wonder, as the translator holds such power to make such distinctions.