ANGELINE KEK WRITES — Motherhood — perhaps the most intimate and universal experience to exist in the universe. Nothing organic can start without it, nothing is left untouched by it. Motherhood transcends all differences. Yet, no singular being’s journey with it is ever quite the same as the next. At the core of understanding these lived experiences is where the simplified questions reveal themselves: What is motherhood? Who is motherhood? Where is motherhood?

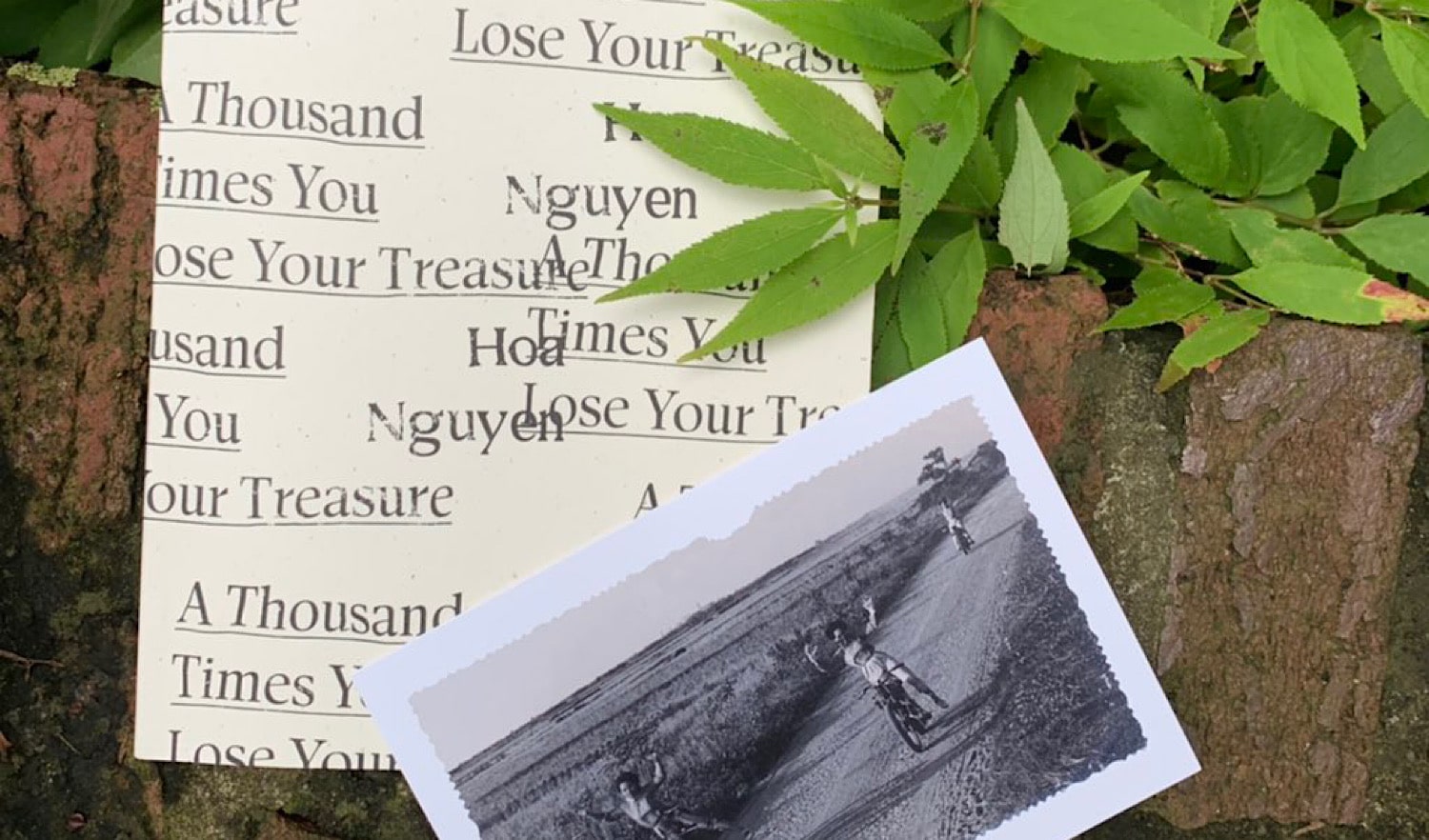

A Thousand Times You Lose Your Treasure (2021) by Vietnamese-American author and celebrated creative writing teacher Hoa Nguyen is a poetry collection that is wildly elusive and refuses simplification. It certainly lives up to the nominations, prizes, and rapturous reviews the author garnered from her previous works which includes As Long As Trees Last, Red Juice: Poems 1998-2008 and Violet Energy Ingots, From the leaping quality of the poems, to the way each poem slips quietly into a different landscape as the page turns, this collection is not easily absorbed, internalized, and appreciated. There are many ways to read this book. However, one of the most that the reader can return to while reading is the framing of motherhood from the perspective of the child throughout the book — the various ways in which the everchanging concept of motherhood leaks into the ink and spills across the poems.

From the first few pages, the reader is introduced to the character of Diệp/Linda, the author’s mother. Even before her name and relevance are revealed, the reader is met with a black and white photograph of a woman perched on top of a sports bike. Posing with one leg on top of the gigantic front wheel, arm on her knee, chin lightly resting on her knuckles.

“This is a special time during 1956, in the olden days I used to be a flying motorcycle artist. This is the only memory of my life.

Gifted to you for keepsake

Flying motorcycle artist”

A Thousand Times You Lose Your Treasure

The speaker’s mother is the definition of dauntless. As a proud member of an all-women motorcycle artist group, she toured Vietnam and lived an unconventional life going against the grain of conservative traditions. In “Tryouts For The Flying Motorist Artist Team, 1958”, the speaker paints the picture of a reckless young girl auditioning for a flying motorist group, determined to try again and again despite falling and bleeding until the group exclaimed “Ok, stop, enough, you’re in!” As she practiced her courageous craft and found her life a series of one risky performance after another, she was not a stranger to moments of “riding shadows on the wall of death”. The speaker’s mother is painted as a blazing fire, refusing to be snuffed to smoke. She is a woman reclaiming womanhood — “the running blue shock of her.”

Woefully, life is never made only of glorious moments. As the Vietnam War (or the American War as it is known in Vietnam) continued ravaging the landscape of the dragon-shaped country, Diệp/Linda finds herself discontented with the conditions which her and her people have been subjected to enduring: “Refusing the motherland mother role / Delta girl plotting a runaway plot / No waiting-in-shadows life for us.” Her venturesome streak carries beyond her passion for flying motor art. It sets her on a journey to a land not ravaged by helicopters and napalm. She leaves the motherland of Vietnam for the United States, a back-breaking start to her life as a refugee and immigrant. Here, in uncharted territory, Diệp/Linda made a life for herself and raised a child.

The speaker, a mixed-blooded Vietnamese poet in a Western land, finds themself musing over topics of racial identity, racism, cultural heritage, and history. With that comes the rightful anger that stems from learning about the history of their people’s displacement under the hands of warfare and ghastly weapons. “Here be chopped things / Infused identity / Anise star or pepper it” — the speaker sees themself as a fusing of two worlds, two cultures. The title “Can’t Write White And Asian” suggests a struggle with identity, where one feels like a borrower of two worlds and a child of neither.

As their mother was displaced from her homeland, the speaker also finds themself with no motherland where they could truly belong. In the U.S., the country that the speaker grew up in, they became aware of a hostility to people who look like them; a twisted amalgamation of otherness and fetishization. To be Asian in the United States is to be an object of desire and yet, of discrimination too. As noted in “From Vogue Magazine 1970” (four years before the Vietnam War ended), the West viewed Asians as monolithic. All the different ethnicities are collectively labeled as ‘oriental’.

Eastern countries and people are mystified, glorified as trends instead of cultures deserving of respect. “This is the year of the orient — [listing various pieces of ‘oriental’ cultures that are cherry-picked to be trends] — all of which appeal to our fantasy in search of the lost paradise…” Not only is it challenging to be Asian in a place that will never count you as one of them, but it is even harder to be a refugee in such a place: “Ching – a cartoon plunder / Chong – a gangplank gratitude / we the / expected happy thankful pleasing.” Refugees are expected to be indebted to the people who ‘took them in’, despite the grim journey it took to escape to another country. To refugees, this country will never see them as an equal who deserves respect. As a mixed-blooded Vietnamese child of a refugee in the United States, the speaker finds themself lacking a sense of belonging. They are removed from the comforting womb of a motherland. While they have found a physical home in another land, the question of a metaphysical home remains unanswered.

The speaker does not explicitly lay out their effort to understand their Vietnamese heritage for the readers to see. Rather, this is shown through the factual yet personal poems about culture, customs, art, and myths. The speaker muses over the indulgence of tragicness in most Vietnamese songs, the ghost legends of the picturesque hills of Đà Lạt, the traditions of Tết (Vietnamese New Year) that might seem peculiar but all have intriguing reasons behind them, the power of intonations, among countless other threads that make up the canvas of what it means to be Vietnamese.

In contrast to these rich poems of culture, the speaker lays bare the facts of war: the different types of “Rainbow Herbicides” unleashed upon the Vietnamese people. How much was used, how often, how long, and how deadly. The speaker simply presents these stories of culture and statistics of war, never once framing themselves within the context of these landscapes. They are holding a mirror up to the reader and saying, “Here are two sides of the same coin.” The Vietnam that the world thinks it knows, and the Vietnam that simply is. Which is to say, there is only one Vietnam, one of art, traditions, culture, people, community, and richness.

Motherhood is the present, the past, and the future. When one finds themself wanting to learn more about motherhood, it sends you down a paper trail of memories and stories. It is confusion, disconnection, unbelonging, and belonging all at once. Often, it is tangled and complicated. Detangling motherhood presents an emotionally exhausting task. Nevertheless, one could never truly be whole without confronting what this rite of life means to them.

Angeline Kek is a book reviewer and contributing staff writer for Asia Media International. As a recent graduate from LMU, she majored in English with a concentration in poetry and creative writing. She is interested in poetry and writings that are unhesitatingly honest.