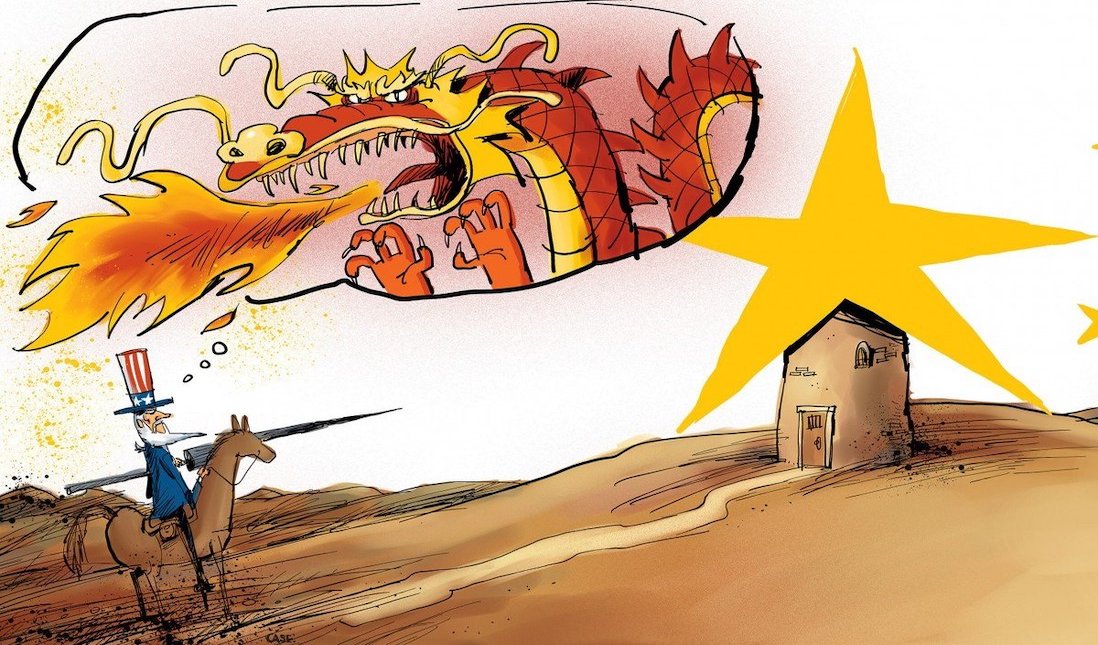

TOM PLATE WRITES — In its quixotic quest for certainty about China – mortal threat or mere robust competitor? – the American consensus now claims to have taken the measure of China and is not in doubt. It would be better if it were. A fictive western mind may be creating something that doesn’t really exist.

It is wrong to be so smug-sure of things, insisted assumption-challenging 17th century Scottish skeptic David Hume: Right, probably the sun will rise over the horizon tomorrow morning – but only probably, don’t be so flat certain. Even quantum physicists accept that measurements, seemingly exact, of the tiniest particles can work out as little more than momentary approximations.

Our growing apprehension of ‘increasingly assertive’ China in part is due to the American character. Our insistence on certainty pressures judgment and undermines needed reflection. We freeze-frame evolving reality into a static snapshot of the present moment. But history moves on no matter that frozen minds remain behind. In his well-titled 1929 book “The Quest for Certainty,” the pragmatist-philosopher John Dewey singled out the corrosive hegemony of ideology and inelastic theory for degrading our ability to cope with reality by getting in the way of it. Dogma feeds on a continual process of self-certification of prior beliefs.

Is communism simply and always evil? And the People’s Republic of China therefore beyond redemption? Consider that capitalism in America’s early days produced many social evils; today it is re-evaluated through a more sophisticated analytical lens due in large part to advancements in social policy. How about China? Communism in the bitter rigid Stalinist practice of the former Soviet Union was one thing; but is it the same thing in China? Are the Chinese even as communist as all that? If less so, is it more dangerous to than ever? Or less? The American quest for certainty, if not clarity, is deeply uncomfortable with ambiguity.

Those who insist that contemporary China is nothing but the Soviet Union redux must contend with the reality of the astoundingly rapid economic and technological advancements under its Communist Party. Anyone who cannot see that is a dogmatist. Anyone who insists the Chinese people are nothing but craven communists do not admit into evidence the fact that prior to the preceding century China was in existence without Marxism or Communism (whose peculiar and revolutionary ideas originated in Europe) — but under centuries of Daoism and Confucianism. Communism did not take the Chinese out of China — it was the reverse: the Chinese took communism and made it Chinese.

Western mass media dogmatism about China and its Xi Jinping underestimates China’s leader especially when, in its yen for certainty, it likens him to one or another past Chinese leader. Western mental constructs construe Xi as if a movie starring a mashup of Deng Xiaoping and Mao Zedong. Analogies can be useful guides to understanding – or, as in this case, symptoms of a tired, stale mentality. Xi’s most obvious characteristic is his singularity. Far more than Mao, for example, Chairman Xi believes in the saving grace of modern science, even to the derogation of the humanities; so, in its emphasis on social stability and scientific development, Xi’s China is less Soviet Union than it is Singapore. Chinese all over know this to be the case, and many admire it.

In all fairness, China doesn’t make it easy for the confused West to figure things out: It’s anything but an open book and doesn’t care to be. This is less a problem for Westerners who, whether they realize it or not, have imprinted in their minds a certain image of China. They see old darkness where there is new light. Consider new books such as ‘China Coup: The Great Leap to Freedom’ (Roger Garside); ‘The Kill Chain: Defending America in the Future of High-Tech Warfare (Christian Brose)’; ‘Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap’ (Graham Allison), and so on. A new entry in the scrum is ‘The Long Game: China’s Grand Strategy to Displace American Order’ (Rush Doshi). It, too, assumes that Beijing will soon be eating the West’s lunch if it doesn’t wake up. Commendably, though, Doshi avoids betting everything on military ‘solutions.’

Alarmist demonization does offer one virtue recognized even by those wise Americans who don’t recognize the evil China that alarmists claim to solely see. The nightmare has America awake. Every offensive military option has been endlessly gamed by the Pentagon and its industrial cadres. An attack that’s a surprise would be unlikely: besides, historically, China doesn’t go in for surprise attacks and has no great avidity for pushing over regimes.

One might even worry that the over-emphasis on China’s rising power might encourage Beijing to dream-walk into a horrible clash with the West. One fervently prays that China and its Xi Jinping team are too smart to play the role marked out for them by America’s fear-mongers, warmongers, and Cold War nostalgia fans. The Chinese and its governors have a titanic job at home: feeding, housing, and educating China’s population. It would be nice to have the West’s help; it would be devastating to believe it is destined for war.

America needs to cope as best it can with what history brings to it and not try to turn back the clock. Of course, it must stay true to allies, including Japan and the Republic of Korea; those U.S. commitments come with the territory and will remain something Beijing has to deal with. For it to think otherwise is deep-dreaming – or taking seriously recent American books. The fictive western mind about China is unbalanced. I am all but certain of that.

Clinical Professor Tom Plate is LMU’s distinguished scholar of Asian and Pacific Studies and vice president of the Pacific Century Institute.