SARAH LOHMANN WRITES – “Does it hurt?” When we hear this question, it is often with an urgent or melancholic tone. Korean author Jungeun Hwang frames the question differently when it is asked of thirteen-year-old Nana by her childhood friend Naghi after he strikes her across the cheek. She confirms it does hurt, and he tells her to remember that feeling: “Forgetting, that’s how people turn monstrous.”

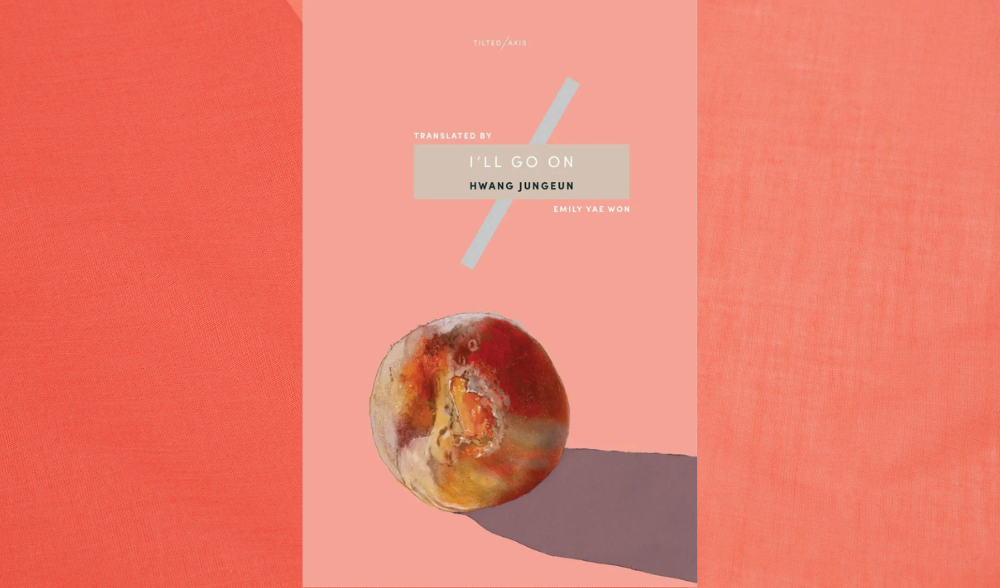

A swirl of nonlinear narratives and memories, I’ll Go On (2018) is a story of discovery and identity. The novel begins with Sora learning her sister Nana is pregnant, causing her own childhood to resurface and lead the reader down alleyway tangents and vivid neighborhoods of the past.

This novel offers exclusive insight into the ways women are expected to exemplify their mothers—and the ways they refute these expectations. Women’s rights continue to be heavily discussed in Korea to this day. Just earlier this year, President Yun Seok-Yul, who garnered strong support among young “anti-feminist” men, pledged to abolish the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family and cut programs that promote gender equality. In a country where women are paid on average a third less than their male counterparts and are poorly represented in the workplace, women are expected to be no more than a mothering machine that makes and cares for their children and in-laws.

Jungeun Hwang is an acclaimed South Korean author. Her works—including One Hundred Shadows (2016) and I’ll Go On—have received numerous accolades. In I’ll Go On, Hwang floats through time, allowing the story’s three narrators to find themselves on their own terms while depicting a reality that is simultaneously fantastical and devastating.

The story is riddled with complex, lifelike conflicts that swell and deplete in waves. The memories of Sora and Nana’s mother, Aeja, and the way she seemed to disappear after her husband’s death, lay the groundwork for the way they continue to process their lives in adulthood. They see the world through the haze of their neglectful—and, at times, completely disconnected—mother versus the maternal stability offered by Naghi’s mother just next door. The inability of a mother figure to exist without the presence of a man clouds the way Sora and Nana are able to conceptualize motherhood and, by extension, the role of the woman in the family.

This becomes especially clear when Nana meets the parents of her husband-to-be. His mother cleans the chamber pot of her husband, which he uses for no reason, as there is a working toilet in the house. Nana’s fiancé justifies this by saying “they’re not other people,” meaning the husband and the wife are not equal beings. This statement reinforces the loneliness of motherhood and the idea of women existing to serve men. In this way, such a concept is unable to be disconnected from its Korean origins—this idea has been passed through generations of women in Korea.

I’ll Go On leads us through a whirlwind, allowing us to wonder when the day will break and what it takes for a woman to be happy. Although there may never be a clear answer, eventually, the moonlight cuts through the darkness. Nana reveals that daybreak must inevitably come, as in real life. “I’ll go on,” she says, and she does.

Sarah Lohmann graduated from Knox College with a BA in Creative Writing and Asian Studies. She focused her studies on film, translation, and Korean culture.

Edited by book review editor-in-chief, Ella Kelleher.